By ANDREW POWELL

Published: March 31, 2015

MUNICH — Arts projects in Europe with any visual aspect to them nowadays migrate to DVD whether or not there is a need, partly to justify public subsidy through distribution. Many are operas filmed too often, like Nationaltheater Mannheim’s just-released Der Ring des Nibelungen, which joins DVD tetralogies from Barcelona, Copenhagen, Erl, Frankfurt, Milan, Stuttgart, Valencia and Weimar issued since 2002. (The same staging nearly bankrupted Los Angeles Opera yet could not be filmed in the movie capital for lack of funds.) Others are more worthy or at least cover rarer material, and generally record labels can license their adventurous content with only modest investment. Here are seven such DVD releases along with some live or live-related European CDs, mostly from recent seasons.

Ivan Alexandre’s staging of Hippolyte et Aricie premiered in 2009 in the intimate Théâtre du Capitole in Toulouse. Its fluid interweaving of Rameau’s vocal and dance elements and credible Personenregie adapted to the composer’s pace earned it a transfer to Paris in 2012, now viewable on a 2-DVD Erato set. Alexandre approaches scenography using methods consistent with period practice and potential. Helped by handsome flat designs and tight control of color, the effects were intriguing and refreshing to watch in both cities’ theaters, and happily they advance the story equally well through the camera lens. Indeed the project is of a quality to set beside Jean-Marie Villégier’s legendary Montpellier production of Lully’s Atys and faithful to Rameau’s tragédie lyrique in a way the modish competing Glyndebourne DVD of 2013 could be only in its audio. Dynamic musicianship underpins the effort, with an admirable cast, notably Stéphane Degout as a mellifluous Thésée (pictured, right, aux enfers). Emmanuelle Haïm’s conducting, all elbows and fists, apparently suits her orchestra, Le Concert d’Astrée.

Warner Classics, the new EMI, has issued a Berlin Philharmonic CD pairing live 2012 and 2010 performances of Rachmaninoff’s Kolokola (Bells) and Symphonic Dances. Simon Rattle’s urbane and at times sultry reading of the cantata — the composer called it a choral symphony — disappoints, with his veteran soprano thin-voiced and only Mikhail Petrenko, his bass in the concluding Mournful Iron Bells, injecting much Russian flavor. But in the dances the conductor’s refinement creates an enthralling balance of power and grace, and he presents a progression from the bucolic first movement, through a hardened Andante con moto, to the contrasts and drama of the suite’s lengthy third part. The string sound has bloom and the woodwinds find a huge range of expression and character.

The Pergolesi tricentennial of 2010 did the Jesi-born Neapolitan composer proud, prompting Claudio Abbado’s priceless 3-CD survey of his choral music as well as a 12-DVD “tutto” collection of the operas, filmed in Jesi. Perhaps the richest single work is the comedy Lo frate ’nnamorato, written at the same time as Hippolyte et Aricie but a world away from it (and pointing forwards to Mozart rather than back at Lully). It is ably led by Fabio Biondi in the big set, but Teatro alla Scala in 1989 had a cast for this opera of charming da capo arias that won’t soon be equaled in technique or liveliness, and their RAI-televised work is currently an Opus Arte DVD. Several Italian singers at the start of good careers — Nuccia Focile, Luciana d’Intino, Bernadette Manca di Nissa, Alessandro Corbelli — energize the story of Ascanio (Focile), “the brother enamored” unknowingly of his two sisters and, luckily, a third woman too. It is unavoidably a larger-scale staging than the piece wants, but Roberto de Simone directs the action neatly on a revolving unit set. The orchestral playing has poise and discipline even if Riccardo Muti propels the score at a tad slower pace than would be ideal.

Twelve years after Cecilia Bartoli’s exploratory Decca disc of rare Gluck arias, the label has issued a companion CD introducing German lyric tenor Daniel Behle. Recorded under sponsorship in Athens in 2013, it leaps out of the loudspeakers. The Bavarian composer’s pre-reform music, now more familiar, can still startle in its inventive turns and loose palettes, and Behle, who sang a riveting Tito in the Mozart opera last fall here at the Staatsoper, opts for several pieces that lie high. In two contrasted arias from La Semiramide riconosciuta he copes manfully with technical demands while keeping power in reserve, as he did on stage. Se povero il ruscello from Ezio brings relaxed lyricism and a mellow timbre that caresses the line. The stunning scena that opens La contesa de’ Numi is duly dramatic. But who oversaw this project? Everything is closely miked. Period orchestra Armonia Atenea accompanies vigorously as led by George Petrou, right in your ear. Misplaced vowel sounds from Behle, in the context of generally accurate delivery, were not fixed. And we jump to French arias at the end, familiar ones, including a bizarrely jovial J’ai perdu mon Eurydice. Producers matter.

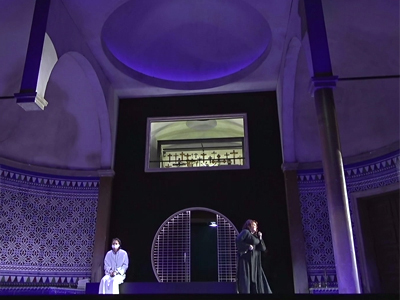

Stage director Pierre Audi in 2009 combined Iphigénie en Aulide and Iphigénie en Tauride for the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, and Christophe Rousset conducted imaginatively over an extended evening as Euripides’ heroine appeared first as teenager in a Greek port and then as adult exile somewhere in Crimea. Two years later Audi’s literally clunky conception — on metal steps and without backdrop — resurfaced in Amsterdam with a mostly changed cast and, alas, Marc Minkowski defining the music through irksome rhythmic stresses, missing much beauty. There it was filmed. Unenhanceable by camera blocking and with Aulide cut by thirty fine minutes, the production is now an Opus Arte 2-DVD set. Gluck’s first opera has the more lyrically inspired and stately score, with a terrific overture; in Tauride his musical frame is tauter and more overtly theatrical. Véronique Gens and Nicolas Testé excel as the young Iphigénie and her father, while Anne Sofie von Otter returns affectingly to Clytemnestre, a role she recorded 24 years earlier; Frédéric Antoun contributes a credible, unstraining Achille. Tauride revolves around the smart Mireille Delunsch, abetted by Yann Beuron (Pylade), Jean-François Lapointe (Oreste) and Laurent Alvaro (Thoas); all sing with imposing dedication.

The less rare Werther received an uncommonly strong cast at the Bastille home of the Opéra National de Paris in 2010, resulting in a 2-DVD Decca set that is reportedly selling well. Sophie Koch and Jonas Kaufmann impersonate Goethe’s awkward soulmates, both fresh of voice. Originally created for London, Benoît Jacquot’s innocuous yet intriguing, glum and sparse production presents the characters faithfully, the action plainly. Unusually Jacquot serves as video director too, lending style by shooting from behind the scenes and above the proscenium as well as from out front. These angles provide glimpses of the conductor, Michel Plasson, who unfortunately blunts the contrasts in Massenet’s score and weighs it down.

When the French, or at least the Franks, helped the Roman Church standardize chant cycles and structures for worship in order to make the liturgy operable and enforceable across regions, their effort left out Milan. Charlemagne’s 8th-century directives invoking St Gregory encouraged steps to document if not yet notate chants, but in the city where St Ambrose had promoted the Church’s adoption of Latin — his small corpse still lies there wondrously on display — a divergent liturgy prevailed. Canto ambrosiano has accordingly stood apart, its manuscripts complete in one place, unlike the scattered repositories of Gregorian chant. In 2010 the Arcidiocesi di Milano, manager of this legacy, commissioned a book and recordings to survey and better disseminate the chants.

The resulting Antifonale Ambrosiano is invaluable. It reproduces scores in early and modern notation. It details Milan’s chant practices in italiano and truly spans the subject: chants for the Ordinary of the Mass and for the Hours (Vigilie, Lodi, Prima, Terza, Sesta, Nona, Vespri, Compieta), chants proper to seasons and saints, chants with psalm and canticle texts — each in one musical line, most to be sung antiphonally. Although not free of audible splices, the recordings are vivid yet with a resonant aura. Italian women and men sing in glorious Latin (and the vernacular), a joy in itself. The three CDs hold about as much music as Parsifal and are issued, with the book, by Libreria Musicale Italiana, an academic body whose website offers a handy carrello and U.S. shipping.

Then there is Bejun Mehta’s Orlando. The countertenor first personified the mad soldier at Glimmerglass in 2003 and must relish the vocal fireworks and range Händel gives him. A performance in Brussels leaked onto video, but in 2013 the same team reconvened in Bruges for a studio recording that Forum Opéra justly hails as an “Orlando d’une époustouflante intensité.” Mehta rises to every ornamental challenge, adjusts his tone to paint words, sings with evenness from bottom to top, and sounds so believably on the fringes of sanity that a Zoroastrian mend is only logical. Senesino lives. But it is not a one-man show. The other principals likewise inhabit their roles even if they crush countless Italian consonants. Sophie Karthäuser: super trills, too closely miked. Sunhae Im: charm in the voice, sweet-sounding. Kristina Hammarström: a focused alto with smooth, masculine tones. Konstantin Wolff: assured and agile. The conducting lacks subtlety but René Jacobs does support his singers, and Ah! Stigie larve! … Vaghe pupille, the accompagnato climax to Act II, properly showcases Mehta. Engineers of the 2-CD Archiv set alas place the B’Rock Orchestra Ghent far forward, so that even the expertly played harpsichord can grate. Fine, fleet woodwinds announce themselves in the overture.

Equally brilliant on a 2012 disc of seldom-heard Mozart concert arias is Rolando Villazón, the tenor whose voice and career were supposedly kaputt. After streamed (and moving) portrayals of Offenbach’s Hoffmann here at the Staatsoper in late 2011, he went to Abbey Road to make this Deutsche Grammophon CD with the London Symphony Orchestra. There the sound engineers proved that the art of balancing musicians hasn’t been totally lost, and conductor Antonio Pappano proved a resilient foil in the bold, precocious, clever, sad, amusing scores, even gracing one aria with a dryly comic bass voice. The results are essential listening, largely because Villazón gets straight to the heart of every piece and finds all the color, truth and humanity anyone could wish for. Even the juvenile work sounds masterly.

Alexander Pereira’s long years as Intendant at Opernhaus Zürich (1991–2012) brought a wave of sponsors for the company and, significantly, its “cantonization,” making it the charge not just of the city but of a wealthy catchment area reaching to the German border. Pereira had a confident ear for talent, built an ensemble, and gave lead roles to unknown singers like the tenors Piotr Beczala (from 1997), Kaufmann (1999) and Javier Camarena (2007). Working with a quintet of conductors — Nikolaus Harnoncourt, William Christie, Nello Santi, Ádám Fischer and Franz Welser-Möst — he widened the audience for the small house through DVDs, ahead of a trend. Two such projects late in the tenure were Rossini operas led by veteran Muhai Tang, with Bartoli, Liliana Nikiteanu, and Camarena in stagings by Patrice Caurier and Moshe Leiser. These are now out on Decca after a delay, poles apart in nature but both vividly impressive.

Stendhal described Rossini’s Otello, ossia Il moro di Venezia, as “volcanic”; certainly it is an unsettling score and a contrast in sensibility to the other heroic operas. Zurich’s staging straddles the line between tragedy and melodrama, with credible interactions and an inner focus that does not let up. Sparse but graphically textured sets lend a tension of their own. Otello needs three tenors who can cope with a high tessitura and sing accurately through wild embellishments, and these it received when filmed in 2012. John Osborn is a duly martial moro, while the romantic role of Rodrigo is ardently taken by Camarena. The two are phenomenal in Ah vieni, nel tuo sangue, their bilious Act II clash. Edgardo Rocha is skilled as Iago (strictly “Jago”), a smaller role. Bass-baritone Peter Kálmán makes an imposing Elmiro (and Graham Chapman lookalike), but the capable women come across less ideally: Bartoli’s Desdemona machine-gun in delivery and Nikiteanu’s Emilia a deer in the headlights. Tang has the mood of the piece and conducts it with unfailing propulsion.

Great fun is Le comte Ory, a farce that brought down the Swiss house when premiered in Jan. 2011. Anyone who knows it through Bartlett Sher’s misfiring production for the Metropolitan Opera owes it to themselves to see Decca’s DVD: it is full of joie de vivre, keenly observed in its humor by the directing partners despite a seven-century advance in the action to 1950s France. Carlos Chausson sang hilariously at the premiere as the Gouverneur, who has a smug early scene, but he is alas replaced in the video (filmed later) by a discomfited Ugo Guagliardo. That said — and the Gouverneur does fade from the plot — there are outstanding musical turns from the other principals and all play the comedy straight. Bartoli moves from Isolier, the suitor role she sang in Milan long ago, to Adèle, Comtesse de Formoutiers, and is a stitch, literally, as directed, exuding dignity except where circumstance overtakes her. Rebeca Olvera essays a chain-smoking warrior of an Isolier. Nikiteanu is deadpan as Ragonde, making sparing use of emotive poses. Camarena smirks sweetly as the “ermite” but upholds due gravity as “Soeur Colette”; he and Oliver Widmer, the excellent Raimbaud, parade the virtues of ensemble acting as well as singing, not to mention comic timing. Tang and the orchestra breezily convey the score’s spirit.

Against the odds, Zimmermann’s Die Soldaten (1964) has become a repertory opera in German-speaking lands. The visionary magnum opus with its depraved storyline sanctions a grab bag of what are now Regietheater clichés, magnified by pluralism, simultaneous scenes and surround sound. Its 110 minutes embrace various musical forms and want a massive orchestra, plus jazz combo, such that, all told, the composer’s concept remains barely feasible. Recent stagings in Salzburg (2012), Zurich (2013*) and Munich (2014*) inevitably went their separate ways; the first, by Alvis Hermanis, is now a EuroArts DVD. Filmed in the Felsenreitschule and presenting a row of arched vignettes mimicking the venue’s rock-carved backdrop, it is preset for simultaneous drama. But once adjusted to the tritone stills of vintage porn backed by live-action images of walking horses, masturbating soldiers and Peeping Toms, the viewer tires of the left-and-right back-and-forth. A striking cast is headed by Laura Aikin as Marie; Ingo Metzmacher works magically with a somewhat backwardly balanced Vienna Philharmonic, not heard with the impact experienced at the venue.

[*Presumably in the DVD pipeline, worth or not worth the wait. Zurich’s has Marc Albrecht conducting a Calixto Bieito concept (less refinement, more degradation, spatially restricted and with lesser musical forces); Munich’s offers Kirill Petrenko on the podium and Andreas Kriegenburg directing traffic (less sex, more clichés). John Rhodes on the Swiss show: “Most sexual perversions and some torture were presented quite graphically … . Marie was in a constant state of undress. At the end she poured blood on herself and stood … as though crucified at the front of the stage.” In Munich the opening scene was overplayed, weakening what followed. Kriegenburg’s box-based staging offered unedifying and in the end unenlightening views, but Petrenko presided over an inflamed Bavarian State Orchestra and a superb cast centered on Barbara Hannigan’s Marie.]

Still image from video © Warner Classics

Related posts:

Spirit of Repušić

Kuhn Paces Bach Oratorio

See-Through Lulu

Petrenko Hosts Petrenko

Carydis Woos Bamberg

Guillaume Tells

Wednesday, September 23rd, 2015By ANDREW POWELL

Published: September 23, 2015

MUNICH — Post is under revision.

Still image from video © Bayerische Staatsoper

Related posts:

Nitrates In the Canapés

Muti the Publisher

Honeck Honors Strauss

Kušej Saps Verdi’s Forza

Time for Schwetzingen

Tags:Amanda Forsythe, Andrew Foster-Williams, Antonino Fogliani, Antonio Pappano, Antú Romero Nunes, Bad Wildbad, Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bongiovanni, Bryan Hymel, Camerata Bach Chor Poznań, CD, Commentary, Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Damiano Michieletto, Dan Ettinger, Decca, DVD, Evgeniya Sotnikova, Gerald Finley, Graham Vick, Guillaume Tell, Günther Groissböck, Jochen Schönleber, John Osborn, Juan Diego Flórez, Judith Howarth, Kritik, Luca Tittoto, Malin Byström, Marina Rebeka, Michael Spyres, Michael Volle, Michele Mariotti, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Naxos, Nicola Alaimo, Nicolas Courjal, Opus Arte, Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Pesaro, Raffaele Facciolà, Review, Rossini, Rossini Opera Festival, Royal Opera House, Sofia Fomina, Tara Stafford, Virtuosi Brunenses

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed