By ANDREW POWELL

Published: August 19, 2016

BAYREUTH — Clouds over Europe’s festivals this summer are as figurative as they are literal. The trouble is not lower standards or Regietheater, or even money, but has to do with Europe itself and macabre shifts that are gradually threatening the way of life accepted since 1945. Last year, you could see it in the organized beggars at the very doors of the Salzburg Festival under the noses of undirected Austrian police. Now it shows, conversely, in a massive security operation around this city’s Festspielhaus. Nobody knows what is coming for the various main seasons.

Consider: nine police vans at Wagner’s theater, forty officers; Arndt Gruppe protective staff, carrying; no visitor walk-around of the building without recourse to the street; segmented access areas; Siegfried-Wagner-Allee closed to vehicles; taxis on a footpath loop to the Liszt-Büste; endless patrols; bag searches (but no metal detectors); and ticket checks at the doors, at the feet of the interior stairs, and on entry to the auditorium. Heightened security was announced months ago — before an Afghan asylum-seeker armed with an ax hurt four people on a train here in Bavaria on July 18, before an Iranian-German obsessed with mass killings shot nine people dead in Munich on July 22, before a Syrian asylum-seeker slew a pregnant woman with a meat cleaver near Stuttgart on July 24, and, pertinently, before another Syrian that same evening botched a plan to explode his metal-piece-filled backpack among two thousand listeners at a different music festival in this state.

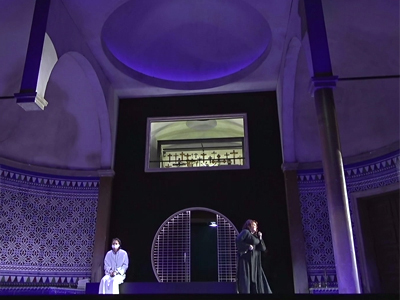

No extra measures applied, the Bayreuth Festival said, for Tristan und Isolde (Aug. 1) or Parsifal (Aug. 2, pictured) with Bundeskanzlerin Angela Merkel in discreet attendance. Both performances upheld high levels of artistry, at least in terms of the listening.

Christian Thielemann, whose impulsive musicianship suits the love-potion work, gauged the score’s climaxes shrewdly and made as much of its barely pulsing nostalgia as of its ecstasies. His hidden orchestra — drawn from a roster of 198 musicians from no fewer than 55 orchestras, 52 of them German — delivered entrancing, duly rapturous sounds, though detail in this instrumentally driven Musikdrama would have registered more luminously in a normal theater. Petra Lang, a past Brangäne for Thielemann and here for the first time an Isolde, produced consistently full and secure dark tones but swallowed much of the text; stage direction presented the promised bride as violent as well as sarcastic. Stephen Gould’s noble Breton tended toward blandness in the high notes, but a musically astute and unstinting portrayal in accented German emerged anyway. Georg Zeppenfeld sang Marke richly, with solid lows, but projected little in the way of authority; being depicted as a kind of thug did not help. Claudia Mahnke’s Brangäne got somewhat quashed by Lang’s timbre and haughty stage presence, while Iain Paterson, as Kurwenal, wobbled vocally on the approach to Cornwall before finding his form.

Hartmut Haenchen’s way with Parsifal, finely executed by the orchestra, brought a perceptive sense of purpose to each phrase, not least in a deeply focused Act I Vorspiel. But the conductor proved less potent in ensembles and dense passages, seemingly unwilling to home in on any single musical line. He had a strong cast: Elena Pankratova, whose thrilling top notes, resonant chest voice and attentive musicianship as Kundry reinforced impressions of a major artist, albeit one who appears to have doubled her weight in three seasons; Klaus Florian Vogt, a pleasing and relatively credible Parsifal; Ryan McKinny, intoning suavely as Amfortas; and Gerd Grochowski, musically incisive but dramatically betrayed as Klingsor. Zeppenfeld, alas, conveyed limited pathos in his neat delivery of Gurnemanz.

Neither of the two stagings offers an uplifting visual counterpart to the music or masterful use of color and form. Katharina Wagner’s considered production of Tristan und Isolde, new last summer, at least allies its Personenregie with cues in the score, and at Kareol musters a plausible probe of Tristan’s mind. But its spaces are confined, notably in Act I when the composer is breathing the sea air. And the young régisseuse undercuts the nobility of both Isolde and Marke. Uwe Eric Laufenberg’s Parsifal staging is at its most poignant as Act III ends and the stage is left bare by exiting Muslims, Christians and a token group of Jews. What comes before is a leaden admonition, set in the unholy and here timeless Middle East, on the perils of religion. Topically for the German audience, it begins with Muslim refugees in Christian sanctuary. Act I’s Verwandlung lifts us on a cosmic flight out of Iraq courtesy of NASA and Google Maps. A quasi-Muslim Gurnemanz hands us off to a quasi-Muslim Klingsor who collects and fetishizes crucifixes. Kundry starts in a hijab, progresses to a mini-dress (in which she bizarrely nods off during her mission to seduce), and terminates as a graying kitchen hag in the service of the ruined knighthood. Less inventively, Laufenberg has Amfortas’ wound parallel Jesus’ stigmata; it won’t heal because the knights keep knifing it open to refill their sacred chalice. So much for ambiguity. DVDs of both operas are promised under a new deal with Deutsche Grammophon.

After a prolonged renovation, the wraps are off the Festspielhaus’s iconic façade for this first summer under the sole leadership of Katharina. The place looks spiffy, an impression reinforced by the uniforms as much as the gowns. A window right next to the unused central door now ventilates a men’s room. Newly sponsored carry-in cushions now enhance comfort in the auditorium. To their credit, festival staff are keeping up an amiable demeanor despite the security strictures. The caterer, meanwhile, is keeping up its margins. Steigenberger Hotel Group, out of Frankfurt, sells a wild boar sausage on a roll for €7 and a small beer for €5.50 (versus €5 for a better sandwich and €3.50 for a beer in Munich’s National Theater); its on-site manager jokes that steep prices pay for the security. In what amounts to a slap in the face for Landkreis Bayreuth’s own pilsners, such as the outstanding Hütten Pils made with water from the same mountain range as above Plzeň, Steigenberger serves a Saxon beer.

BR Klassik will audio-stream the Aug. 1 Tristan und Isolde at 12:05 p.m. EDT on Aug. 27, 2016, here. Video of the opening night of Parsifal (July 25) is here: Act I, Act II, Act III.

Still image from video © BR Klassik

Related posts:

Kaufmann, Wife Separate

Parsifal the Environmentalist

See-Through Lulu

U.S. Orchestras on Travel Ban

Nitrates In the Canapés