By Rachel Straus

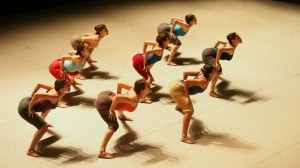

Mark Morris’ A Forest (seen May 21) premiered at the Mark Morris Dance Center in downtown Brooklyn, now a construction zone where multiple glass skyscrapers dwarf the once prominent, white dance building. As if in response, Morris’s Forest choreography to Haydn’s elegant sonorities, from Piano Trio No. 44 n E Major, is often treated with slight dance responses. For example, when MMDG Music Ensemble pianist Colin Fowler, violinist Georgy Valtchev, and cellist Wolfram Koessel introduced Hayden’s primary theme, and later repeated it, the nine talented dancers became Pavlovians, dutifully repeating the same dance phrase. Part of their dance phrase involved hopping three times in three clumps, and in time with the musicians’ strident triple bowing and fingering. They brought to mind excited kids at a candy store.

All the Forest dancers wore white unitards with a geometric pattern that looked just like Victorian wallpaper of Acanthus leaves. Maile Okamura’s costumes reinforced the notions that nature is a distant memory, a simulacrum of a simulacrum, and that the dancers’ bodies are in service of the choreographer’s design.

Morris’s newest work, part of his insouciant genre, makes me wonder what Haydn would make of his cheeky approach. That said, the dancers never mugged the audience. Their serious, straight-forward demeanor, even when they were dancing comically to the music, brought to mind humanistic automatons strictly tethered to the beat. In the final movement, when Koessel plucked his cello, several of the dancers dropped to the floor like felled trees, thus connecting (for me) the cello’s mellow force to the more violent energy of the jackhammer (outside).

At the final bows, Morris reinforced the perception that the dancers are not free agents. When he entered, and took his place in line, he flicked his hands apart and the dancers ran to the wings. When he was ready for his third bow, he flicked his hands together. Voila! They rejoined him. My companion, a classical music expert, stopped clapping at this point. She was not amused by Morris’ public deprecation of these fine artists.

Unlike Cargo (2005)—where the dancers wear Jockey-like baggy underwear and pretend to be primitives—Foursome (2002) and The (2015) treated the dancers with greater reverence. Foursome is set to Erik Satie’s Gnossiennes #1, #2 and #3, and was played with delicate sophistication by Fowler. Thanks to Katherine M. Patterson’s costuming, the four male dancers are immediately individualized. Domingo Estrada Jr. (is the urban sophisticate), Noah Vinson (a 1970s dancer), lanky Billy Smith (the cowboy) and Dallas McMurray (junior golfer). Costume eccentricities aside, the dancers performed somberly, reflecting the hushed power of Satie’s first and second songs. Morris gave them walks, which seemed to freeze each time they reached the end of their stride, consequently providing a half photograph, half lived experience. Foursome‘s pleasure includes its emotional arc. It moves from slow and fragmented to fulsome and joyful. The last song was a delight, with the men transforming into proud folk dancers, their chests puffed high, hand pressed to their chests, and feet pounding rhythmically in the floor. Their musicality was infectious.

The, which completed the program, was the only work to feature the full company (16 of the 18 performers). Commissioned last year by the Tanglewood Music Center for the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s 75th anniversary, The reveals Morris’ love for Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F Major. Pianists Fowler and George Shevtsov performed the version arranged for four hands by Max Reger. Yet the dancers juicy, buoyant attack made it seem as though they were performing with a full orchestra. They even were given permission to smile. The is Morris at his most humane. The dancers are the song, appearing to make the musical phrases sing more energetically. Their collective sensibility presented an ideal, the forging of a community of inspired music and dance artists.