By ANDREW POWELL

Published: October 29, 2016

RAVENNA — Imprints, sub-brands, and discreet licensing entities were once a way for artists with bargaining power to secure fatter stakes in the published output of their work. Among conductors, Herbert von Karajan, Leonard Bernstein and Nikolaus Harnoncourt enjoyed the privilege.

Are such endeavors still viable, given social media and the glutted commercial market for sound and video recordings? One artist who is surely finding out is Riccardo Muti. Some years ago he set up RMM, or RM Music Srl, here on the neat stone alley linking Dante’s tomb with Teatro Alighieri, main venue of the Ravenna Festival.

This is, sources say, a family business intended to provide income streams into the future for the maestro’s children: Francesco, 45, an architect; Chiara, 43, actress and stage director; and Domenico, 37, laureato in legge and in charge of contracts.

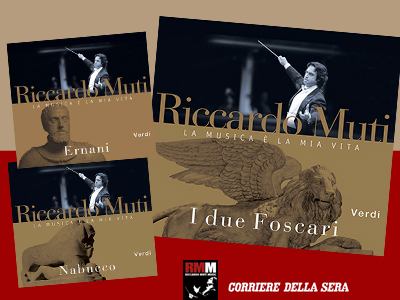

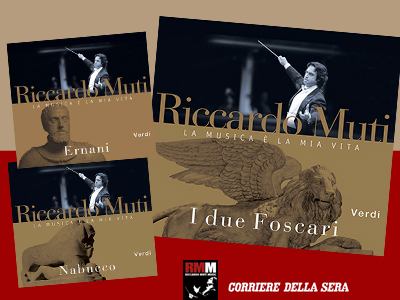

Holding “all the image and recording rights of Riccardo Muti,” no less, RMM produces, publishes, and licenses on its own account and in association with such names as Corriere della Sera and CSO Resound — the former an Italian daily newspaper, the latter a nine-year-old Chicago Symphony Orchestra “response to the upheaval in the music industry.”

Unlike those departed maestros coddled by Bertelsmann, Sony or Universal, Muti is charting an autonomous, probably arduous, path involving rights-retention, brand-building, and deal-adjusted marketing strategies. On its own, RMM lacks clout. In association with others, it must permit assorted offerings and suffer faults in packaging and distribution.

Worthy products bearing RMM’s stamp-like logo face the same hurdles to profitability nowadays confronting the conglomerates, on less publicity. It is practically a secret, for instance, that three new Muti-led Verdi opera recordings arrived on the market this past spring.

Nonetheless RMM operates as cagily as a pure-play licensor, disclosing little online. For this post, it declined an invitation to expound on mission or plans. RCS MediaGroup, which runs the newspaper and calls RMM a “partner,” said it had to confer before confirming the success of a lengthy recent operazione congiunta, and in the end could not.

The conductor began discernibly to tighten control over recordings of his work after Decca’s DVD release of the 2006 Salzburg Die Zauberflöte. This was and remains his last new release on a “major” label, a remarkable halt considering his eminence.

Rights started to move to RMM almost certainly through revised clauses in Muti’s engagement contracts, including those with orchestras, opera companies and festivals whose output is broadcast using public money.

The pace of Muti releases then slowed. In the nine years through last December, only a handful of new orchestral discs appeared, and only three opera issues — a 2008 Salzburg Otello DVD on the lately launched C Major label; a 2011 Otello audio CD set from Chicago; and Mercadante’s I due Figaro, recorded in 2011 for Ducale.

More recently, though, any instinct to restrict supply has given way to pragmatism. RMM products have grown in number despite market conditions. (The glut was not in any case constraining promoters of less bankable artists, or issuers of pirate Muti discs.) Even with these, however, an attractive backlog remains of unreleased broadcast recordings of the conductor’s work.

RMM as a standalone label tends toward specialty discs, many featuring the Orchestra Cherubini, based here. An 11-hour DVD set of orchestral rehearsals, led in Italian and wide-ranging in repertory, will be among the most prized of these long-term. Packaged in saintly white, it sells for €99. Then there is a 100-minute documentary about conducting Verdi; “assolutamente trascinante,” reads one plaudit.

The lineup, RMM-produced, can be sampled and acquired on the company’s website, but not, pointedly, at the ubiquitous online retailer or through channels outside Italy.

Of RMM’s deals, one with Warner Classics presumably earns revenue. The 2013 Verdi documentary, filmed in Chicago and Rome and directed by Gabriele Cazzola, fittingly caps the American company’s new single-box reissue of all eleven of Muti’s former EMI Verdi opera sets. This represents something of a bargain, at about $75, under a dark and piercing RMM cover image.

RMM’s largest project has been with the Corriere’s distribution arm: a €317 collection of 32 Muti titles (roughly 50 CDs) chosen by the artist himself and classically presented in black and bronze. Finalized in August after a 32-week rollout, it carries the banner La musica è la mia vita.

It is also, alas, a jumble. Most of the discs are reissues stretching as far back as 1970s concerto recordings with Sviatoslav Richter and the old Aida with the New Philharmonia Orchestra. Later efforts from Philadelphia and Vienna occupy much space. Inevitably many collectors will already own parts of the set.

Yet hidden in the huge box are three legitimate new Verdi opera recordings that would once have caused a global stir. They originate in strongly cast live performances during the Verdi bicentennial year of 2013 at the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma:

— Nabucco, with Tatiana Serjan (as Abigaille), Sonia Ganassi (Fenena), Francesco Meli (Ismaele), Luca Salsi (Nabucco) and Riccardo Zanellato (Zaccaria);

— I due Foscari, the most recent of seventeen Verdi operas now in Muti’s repertory, with Serjan (Lucrezia), Meli (Jacopo) and Salsi (Francesco); and

— Ernani, with Serjan (Elvira), Meli (Ernani), Salsi (Carlo) and Ildar Abdrazakov (Silva).

Rome’s production of the biblical opera had made news two years earlier when Muti lectured Italy’s politicos — President Giorgio Napolitano and Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi each attended at least once — on the perils of low cultural subsidies. Halting one performance, he related Italy’s destiny to the “beautiful and lost” Jewish homeland before indulging the house in a leaden Và, pensiero, sull’ali dorate sing-along.

Aptly enough for a newspaper company, Corriere della Sera’s slow rollout took place on newsstands across this country, allowing buyers to skip unwanted titles if they could do without the “unedited little book of [Muti] memories and anecdotes” included in the set.

Cost per title: a modest €10.90, whether one, two, or, for Guillaume Tell in Italian, four discs. News vendors on Piazza dei Caduti and Piazza del Popolo here reported sales of “tanti” discs and “un successo,” evidently freer to speak than RCS MediaGroup.

At the Corriere’s online store, shipping can be arranged worldwide. But product details are missing. Shoppers see only the front covers and a footnote about the recording source. The new Verdi items come up without casts.

With the Chicago orchestra, RMM has weaker terms. The CSO made clear this month that it holds sole copyright in CSO Resound recordings and that RMM’s stamp, present by agreement on five of its published titles, indicates no financial participation by the Muti family entity. Nor is the label intended to function as a profit center within the umbrella CSO nonprofit, the orchestra said.

RMM-branded discs and downloads on CSO Resound are a motley array, no doubt reflecting goals and realities other than Muti’s artistic emphases as Chicago Symphony Orchestra music director.

Issued: a Berlioz pairing of Symphonie fantastique with Lélio, ou Le retour à la vie (2010, much delayed); Schönberg’s Kol Nidre coupled with Shostakovich’s Suite on Verses of Michelangelo (2012, much delayed); Mason Bates’ symphony Alternative Energy and Anna Clyne’s “sonic portrait” Night Ferry (2012); numbers from the first two of Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet suites (2013); and Bates’ Anthology of Fantastic Zoology (2015).

Those realities have to do with how orchestras raise funds in the U.S. — meaning conditions or incentives attendant on specific subsidizing grants and gifts — and naturally whether a product is considered saleable. The Zoology item has sold relatively well, the CSO said, without providing figures.

Having no stake, managers at RMM have no reason to care about CSO Resound repertory, but other observers away from South Michigan Avenue — and record buyers — must wonder at the lack of music from the Classical period, where Muti excels. His discerning Schubert, for example. Moreover the CSO would not confirm it will issue the Verdi Macbeth it recorded in 2013, or Falstaff, basketed a few months ago.

As for RMM’s stamp, it appears merely “in support of [Muti] and his wider activities around the world,” explained the orchestra with lawyerly reticence. (It is omitted from two Verdi issues on CSO Resound, the mentioned Otello and a recording of the Requiem Mass made before Muti assumed his post.)

CSO Resound gives RMM visibility Stateside and has good distribution, using multiple online retailers for disc and download versions of most titles.

The label’s packaging, on the other hand, with crude typography and slipshod billing, cannot match RMM products created in Italy. Take the Berlioz disc. Finally released in 2015, five years after being recorded, its cover declares “Chicago Symphony” three times, plus “CSO”; lists the conductor before the orchestra, then the soloists, whose names are separated by a slash, and chorus; and allows the most noteworthy item, Lélio, to get lost essentially.

Muti the publisher, then, faces a host of hurdles. For RMM to be viable, never mind guarantee long-term family income, it needs all elements pulling in its favor. It must balance the pros and cons of independence against those of joint ventures while avoiding unforced errors such as caginess, intentional product delays and narrowed distribution.

At a glance, its best prospects lie in content from tax-supported broadcasts, as newly marketed. WFMT, WQXR, Italy’s RAI and Austria’s ORF have all aired the conductor’s work since 2006, filmed or taped. Standards are high, and in terms of production the output is largely ready for release — ready, but at present held up and falling to pirates.

Listing just operas, and not counting items discussed above, RMM may have “recording rights” in: Il ritorno di Don Calandrino (Salzburg) and Sancta Susanna (New York), from 2007; Così fan tutte and Don Pasquale (both Vienna), 2008; Iphigénie en Aulide (Rome) and Moïse et Pharaon (Salzburg), 2009; Attila (New York) and Orfeo ed Euridice (Salzburg), 2010; Macbeth (Salzburg), 2011; Simon Boccanegra (Rome), filmed in 2012; and Manon Lescaut (Rome), 2014 audio.

There is a solid if limited market on DVD or CD for this body of work, and one instinctively wishes the family venture every success in using the associated rights, even if the era has likely ended when imprints could assure fortunes.

That said, Riccardo Muti’s personal priority may be something else: legacy. His own, and more emphatically the artistic traditions he values. Hence the not necessarily lucrative documenting of preparation and rehearsal methods in RMM productions. It is no coincidence his Italian Opera Academy is headquartered on the same alley.

Images © RM Music Srl and RCS MediaGroup

Related posts:

Muti Taps the Liturgy

MPhil Bosses Want Continuity

Winter Discs

Netrebko, Barcellona in Aida

Concert Hall Design Chosen

Five More Years

Wednesday, February 21st, 2018By ANDREW POWELL

Published: February 21, 2018

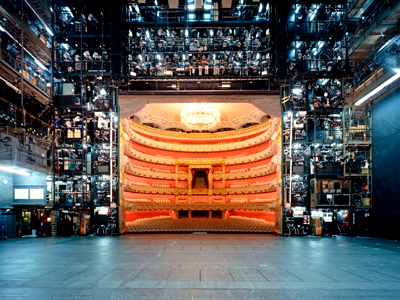

MUNICH — Putting box-office steadiness ahead of artistic achievement, the city council here voted this morning to extend by five years Valery Gergiev’s contract as Chefdirigent of the civically run Munich Philharmonic, as requested by the orchestra’s managers. The move doubles the Russian’s tenure, to encompass the seasons 2020–25. No salary was disclosed, as usual, but past reports have shown €800,000 as an annual figure.

Matthias Ambrosius, spokesman for the musicians, and clarinetist, noted in writing that the “vast majority” of MPhil players had wanted to lengthen the collaboration with Gergiev. Nonetheless it is widely understood that the managers’ request stemmed from a desire to ease dislocation of the orchestra in 2020, when a massive project to reconfigure its Gasteig home begins. Gergiev will in this sense be doing the city a favor, gamely cooperating for seasons at a temporary concert hall.

Photo © Landeshauptstadt München

Related posts:

MPhil Bosses Want Continuity

Bruckner’s First, Twice

Flitting Thru Prokofiev

Netrebko, Barcellona in Aida

Honeck Honors Strauss

Tags:Commentary, Gasteig, München, Münchner Philharmoniker, Munich, Munich Philharmonic, News, Valery Gergiev

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed