by Albert Innaurato

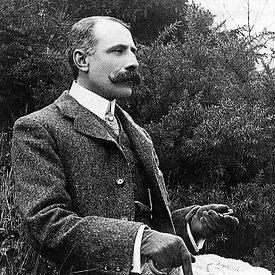

Elgar (the quote above is his) chats with George Bernard Shaw. Sir Edward owed Shaw 1000 pounds! Lady Elgar died in 1921, Elgar was devastated. Whatever their amorous intimacy, Alice had been everything else to Elgar. Her passionate belief was more crucial after WW 1 than it had been since the early days. His reputation post war was at low ebb (ironically, both he and Alice had hated the war). He wrote elaborate chamber music, but a piece adored today, The Cello Concerto, was a disaster at its world premiere. After Alice’s death, Elgar slowed down, dining with his dogs and often running off to the races. He derided the “folk song” collectors in England and around the world, and was puzzled by Stravinsky, and the experimental and intellectual movements gaining force in Europe.

But there is OWLS: remarkable texture, arresting harmonic gestures and an overwhelming sorrow that seems very much of the 1920’s — except it was composed on New Year’s Eve, 1907. Elgar had something of the prophet in him.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U7JnIjK1ML4

Vera Hockman, a “semi-professional” violinist was at one of the back desks at a performance of the Dream of Gerontius he was conducting in 1931, and he whisked her off for — Manhattans — a choice of drink considered impossibly daring. Vera was highly intelligent with an impressive circle of friends including “Uncle Ralph” (Vaughan Williams), and she was separated from her husband, a rabbi. Once again, Elgar wrote letters that leave little doubt that at least for a time this was a physical relationship — although he was 74 and she was 40. Ideas for big pieces flooded his brain. His source for composition had always been from his own emotion and experiences. Vera awakened irresistible impulses. It seems that the Third Symphony was Shaw’s idea; he wanted his money back and advised the composer to demand that the BBC commission it (they did). But Vera was passionate about his work. He called her “My mother, child, lover, friend”. In one of the sketches of the Third Symphony, he wrote “Vera’s own tune.” Elgar did not live to finish this work, it was completed by Alexander Payne to a mixed reception (usual with completions) but one can’t miss the energy in the work, and one tune, associated with Vera, is especially arresting.

In this period, Elgar also became one of the first serious composers to record a lot of his music. Possibly fees and royalties had something to do with it, he was no longer earning very much, but among others, he made a very famous recording of The Violin Concerto with Yehudi Menuhin, then 16.

He died of cancer and was often in considerable pain (but 32 days before his death he supervised a recording of Caractacus over the telephone).

Elgar was attacked after his death for his conservatism. Young English musicians associated that as much with The Edwardian era as they did with the actual quality of his music. Inevitably, the “old days” seemed less bad after the Depression and Second World War, and rehabilitation came, helped by a flood of recordings on long playing records by conductors Elgar had cultivated when they were young and unknown, including Adrian Boult and John Barbirolli. Even Benjamin Britten came around somewhat after condemning Elgar (and many other composers) as amateurs — but he had written a masterpiece, the very radical, disastrously received Our Hunting Fathers only two years after Elgar’ s death. He never forgot the open mockery of the London Philharmonic Orchestra from which he had to be rescued by Ralph Vaughan Williams, whose music he detested.

Any opinion offered of a creative artist has no value unless most of the work is considered, and even then, it is a product of personal experience, expectation and limitation. After listening to and reading a lot of Elgar I remain skeptical about many of the large works. It seems to me, he was primarily a remarkably gifted inventor of tunes, and also very good at setting them so that they “landed”. Oddly enough, that puts him in the same boat as many of those detested opera composers who could come up with strong melodic material but could only rely on convention and hope in organizing it. Music of this kind often acts as an intoxicant and for many that’s enough.

As a person, it’s interesting that many of the distinguished musicians interviewed in Elgar The Man behind the Music, a terrific film by John Bridcut, say they are sure they would have disliked or even detested him. But how can one know what is real about someone who is so self invented? The rigid class codes of the time made it essential for Elgar to control his public image and behavior. As is true of many artists he did not treat everyone well, but the letters show genuine “heart”. I don’t think that’s so bad,; but I do suspect he would have disliked me!

Vaughan Williams had admitted the 16 year old Britten to the Royal Academy of Music with a scholarship, which did not redeem him in Ben’s eyes. But one person Ben could not consider an amateur was the phenomenon, Thomas Tallis. There is a piece a musician described during rehearsals as “A queer, mad work by an odd fellow from Chelsea”. It is the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis by Ralph Vaughan Williams. It is a marriage between Elizabethan and Victorian composers that will surely last as long as anything by the great Benjamin Britten!

So before running out of steam, a threat: I’ll babble on about Tallis, Vaughan Williams and a bit about Ben, that will be our own version of 50 shades of grey!