By ANDREW POWELL

Published: January 8, 2013

RAVENNA — Sacred music has lent gravitas to Riccardo Muti’s career since the 1960s. Settings of the Ordinary and the burial service by Bach, Mozart, Cherubini, Schubert, Berlioz, Brahms and Verdi have drawn his attention and received, more often than not, a disciplined performance.

No, this is not the repertory that leaps to mind when discussing the maestro from Molfetta. The operas of Verdi come first, and peer names like Arturo Toscanini, Herbert von Karajan and Claudio Abbado are soon raised. Muti the Verdian enjoys high standing — so high that he will be valued long after his own burial service for a trove of Verdi readings wider than Abbado’s, more eloquent than Karajan’s and better sung than Toscanini’s. (In context, it is worth hoping that his new biography of the composer will offer greater insight than his patchy 2010 autobiography.)

But music for the church points to the heart of this artist more directly than any opera. Where Abbado sees himself as a gardener, Muti’s alter ego is equipped as historian. Muti studies and diligently performs Mass settings — and antiphons, canticles, hymns and oratorios — out of a perceptive sense of their place in history, in a composer’s output, in the genesis of compositional technique and thought.

The effort is somewhat thankless. Sacred scores, particularly whole services, lack sway in a secular society and often lack musical balance too because of the characteristics of the liturgical sections. Many are front-loaded by a euphoric Gloria. Most end soberly, Haydn’s Paukenmesse being an exception to prove the rule. An established conductor who is not a choral conductor needs no Mass setting to boost his reputation, impress authenticists, sell tickets or oblige a record company. Yet Muti has forged ahead, Pimen-like, documenting scores others have not deigned to read. In one championing example, he has chronicled in sound no fewer than seven services by Cherubini.

In 2012–13 three sacred-music projects occupy him. Last August with the Vienna Philharmonic he persuasively reasserted his advocacy of Berlioz’s flamboyant, long-mislaid Messe solennelle, which he sees as a tribute to Cherubini, and this April in Chicago he revisits Bach’s B-Minor Mass.

Three weeks ago in Munich came Schubert’s A-Flat service, a non-commission from 1822 (D678). The songsmith struggled with its form. He did not follow early polyphonic precedent in imposing thematic unity; did not enjoy Bach’s or Haydn’s flair for satisfying church provisos while enhancing structure; did not write his own rules as would Berlioz and Verdi. Five handsome musico-liturgical sections were the result. A serene Kyrie and a radiant Agnus Dei, each with inventive, contrasting subsections. A protracted and prodigious, finally portentous, Gloria. A Credo that covers its narrative ground with storyteller fluency. A pastel-pretty Sanctus sequence. Call them Mass movements in search of containment.

Undeterred by the implicit challenge, Muti for his Dec. 20 concert with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra chose an 1826 revision that caps the Gloria with a bulky fugue, for Cum Sancto Spiritu. He made no attempt to harness Schubert’s ideas: sectional detachment and stylistic incongruities spoke for themselves, often elegantly.

Vocal and instrumental forces cooperated under tight reign, temporal more than dynamic. The BR Chor sang with customary refinement, applying Teutonic conventions in the Latin text. Ruth Ziesak and Michele Pertusi reprised the parts they took when Muti led this music in Milan’s Basilica di San Marco ten years ago. Still fresh of voice and keen to give notes their full value, the soprano found her form promptly after a grainy opening to the Christe eleison. Pertusi, in the modest bass part, blended neatly with his colleagues. Alisa Kolosova contributed an opulent alto, Saimir Pirgu an articulate, secure tenor; he participates in all three of the conductor’s Mass projects in 2012–13. On the Herkulessaal program’s first half, Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony received a mundane traversal except in its agitated fourth movement, where taut rhythms left a lingering impression. The orchestra played attentively in both works.

Tepid applause followed the Mass, a contrast to the cheers that had erupted in Salzburg after the Berlioz work. Was this foreseen? Disappointing? In Italy they say Muti is addicted to applause. More likely is that audience reaction is beside the point for him: he simply wants clean execution, and he received it in Munich. Muti: “ … non siamo degli intrattenitori. La nostra professione è di un impegno maggiore … .” Pimen turns another page.

Toscanini and Karajan, those fellow Verdians, are not remembered for works destined to fall flat in concert. Both built careers on small sacred repertories: some half-dozen Mass settings each, beyond the not-quite-liturgical requiems of Brahms and Verdi. Beethoven’s hyper-developed and intimidating Missa solemnis had pride of place. Karajan revered the Bach as well (29 performances) and occasionally turned to Mozart’s Great C-Minor Mass and Requiem.

Abbado has, like Muti, taken up two Mass settings by Schubert: the tuneful early G-Major, which Muti performed in Milan twelve years ago, and the resourceful, variegated E-Flat Mass, the composer’s last. This work he paired with Mozart’s Waisenhausmesse (1768) in a jolly two-service concert in Salzburg six months ago. Both conductors have performed the two mature Mozart works and the Brahms and Verdi, but curiously neither man has tried a Mass setting by Haydn or Beethoven, casual research suggests.

To be sure, sacred music is not the mainstay of Muti’s career. His commitments to the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and to Italy’s young-professional Orchestra Cherubini pull the emphasis elsewhere. But the passion for historical context that drives his Mass projects also shapes his priorities in symphonic repertory and opera. Instilled surely during formative years in Naples, it accounts for starkly independent programming choices and probably explains his famously firm way with the details of a score: the chronicler demands accuracy as well as loyalty to the composer. A tempo, però!

By happenstance this post is being drafted a few yards from the home of Muti and the tomb of Dante. They lie in opposite directions.

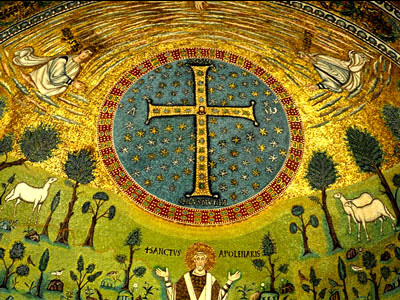

Photo © Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e Paesaggistici

Related posts:

Spirit of Repušić

Muti Crowns Charles X

Muti the Publisher

Netrebko, Barcellona in Aida

Safety First at Bayreuth

Muti Taps the Liturgy

Tuesday, January 8th, 2013By ANDREW POWELL

Published: January 8, 2013

RAVENNA — Sacred music has lent gravitas to Riccardo Muti’s career since the 1960s. Settings of the Ordinary and the burial service by Bach, Mozart, Cherubini, Schubert, Berlioz, Brahms and Verdi have drawn his attention and received, more often than not, a disciplined performance.

No, this is not the repertory that leaps to mind when discussing the maestro from Molfetta. The operas of Verdi come first, and peer names like Arturo Toscanini, Herbert von Karajan and Claudio Abbado are soon raised. Muti the Verdian enjoys high standing — so high that he will be valued long after his own burial service for a trove of Verdi readings wider than Abbado’s, more eloquent than Karajan’s and better sung than Toscanini’s. (In context, it is worth hoping that his new biography of the composer will offer greater insight than his patchy 2010 autobiography.)

But music for the church points to the heart of this artist more directly than any opera. Where Abbado sees himself as a gardener, Muti’s alter ego is equipped as historian. Muti studies and diligently performs Mass settings — and antiphons, canticles, hymns and oratorios — out of a perceptive sense of their place in history, in a composer’s output, in the genesis of compositional technique and thought.

The effort is somewhat thankless. Sacred scores, particularly whole services, lack sway in a secular society and often lack musical balance too because of the characteristics of the liturgical sections. Many are front-loaded by a euphoric Gloria. Most end soberly, Haydn’s Paukenmesse being an exception to prove the rule. An established conductor who is not a choral conductor needs no Mass setting to boost his reputation, impress authenticists, sell tickets or oblige a record company. Yet Muti has forged ahead, Pimen-like, documenting scores others have not deigned to read. In one championing example, he has chronicled in sound no fewer than seven services by Cherubini.

In 2012–13 three sacred-music projects occupy him. Last August with the Vienna Philharmonic he persuasively reasserted his advocacy of Berlioz’s flamboyant, long-mislaid Messe solennelle, which he sees as a tribute to Cherubini, and this April in Chicago he revisits Bach’s B-Minor Mass.

Three weeks ago in Munich came Schubert’s A-Flat service, a non-commission from 1822 (D678). The songsmith struggled with its form. He did not follow early polyphonic precedent in imposing thematic unity; did not enjoy Bach’s or Haydn’s flair for satisfying church provisos while enhancing structure; did not write his own rules as would Berlioz and Verdi. Five handsome musico-liturgical sections were the result. A serene Kyrie and a radiant Agnus Dei, each with inventive, contrasting subsections. A protracted and prodigious, finally portentous, Gloria. A Credo that covers its narrative ground with storyteller fluency. A pastel-pretty Sanctus sequence. Call them Mass movements in search of containment.

Undeterred by the implicit challenge, Muti for his Dec. 20 concert with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra chose an 1826 revision that caps the Gloria with a bulky fugue, for Cum Sancto Spiritu. He made no attempt to harness Schubert’s ideas: sectional detachment and stylistic incongruities spoke for themselves, often elegantly.

Vocal and instrumental forces cooperated under tight reign, temporal more than dynamic. The BR Chor sang with customary refinement, applying Teutonic conventions in the Latin text. Ruth Ziesak and Michele Pertusi reprised the parts they took when Muti led this music in Milan’s Basilica di San Marco ten years ago. Still fresh of voice and keen to give notes their full value, the soprano found her form promptly after a grainy opening to the Christe eleison. Pertusi, in the modest bass part, blended neatly with his colleagues. Alisa Kolosova contributed an opulent alto, Saimir Pirgu an articulate, secure tenor; he participates in all three of the conductor’s Mass projects in 2012–13. On the Herkulessaal program’s first half, Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony received a mundane traversal except in its agitated fourth movement, where taut rhythms left a lingering impression. The orchestra played attentively in both works.

Tepid applause followed the Mass, a contrast to the cheers that had erupted in Salzburg after the Berlioz work. Was this foreseen? Disappointing? In Italy they say Muti is addicted to applause. More likely is that audience reaction is beside the point for him: he simply wants clean execution, and he received it in Munich. Muti: “ … non siamo degli intrattenitori. La nostra professione è di un impegno maggiore … .” Pimen turns another page.

Toscanini and Karajan, those fellow Verdians, are not remembered for works destined to fall flat in concert. Both built careers on small sacred repertories: some half-dozen Mass settings each, beyond the not-quite-liturgical requiems of Brahms and Verdi. Beethoven’s hyper-developed and intimidating Missa solemnis had pride of place. Karajan revered the Bach as well (29 performances) and occasionally turned to Mozart’s Great C-Minor Mass and Requiem.

Abbado has, like Muti, taken up two Mass settings by Schubert: the tuneful early G-Major, which Muti performed in Milan twelve years ago, and the resourceful, variegated E-Flat Mass, the composer’s last. This work he paired with Mozart’s Waisenhausmesse (1768) in a jolly two-service concert in Salzburg six months ago. Both conductors have performed the two mature Mozart works and the Brahms and Verdi, but curiously neither man has tried a Mass setting by Haydn or Beethoven, casual research suggests.

To be sure, sacred music is not the mainstay of Muti’s career. His commitments to the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and to Italy’s young-professional Orchestra Cherubini pull the emphasis elsewhere. But the passion for historical context that drives his Mass projects also shapes his priorities in symphonic repertory and opera. Instilled surely during formative years in Naples, it accounts for starkly independent programming choices and probably explains his famously firm way with the details of a score: the chronicler demands accuracy as well as loyalty to the composer. A tempo, però!

By happenstance this post is being drafted a few yards from the home of Muti and the tomb of Dante. They lie in opposite directions.

Photo © Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e Paesaggistici

Related posts:

Spirit of Repušić

Muti Crowns Charles X

Muti the Publisher

Netrebko, Barcellona in Aida

Safety First at Bayreuth

Tags:Alisa Kolosova, Arturo Toscanini, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, BR Chor, Cherubini, Claudio Abbado, Commentary, Giuseppe Verdi, Herbert von Karajan, Michele Pertusi, München, Munich, Orchestra Cherubini, Ravenna, Recensione, Review, Riccardo Muti, Rome Opera, Ruth Ziesak, Saimir Pirgu, Schubert, Symphonie-Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed