By Rebecca Schmid

The Komische Oper champions a populist approach through German-language productions and contemporary stage concepts that for some opera goers is synonymous with the most vexing of Regietheater. While the emphasis of the company’s founder Walter Felsenstein on living theater above musical purity remains a locally prized virtue, the house’s attendance rate sank from an already low 61% to 59% last year while that of the Deutsche Oper increased by 11%. The critical reception to recent premieres such as Calixto Bieto’s “16 and older” Der Freischütz and Thilo Reinhardt’s phallus-ridden Salome has also been mostly unfavorable.

Yet as the adventurous tenure of Intendant Andreas Homoki draws to a close, the house may be headed in a new direction. The incoming Barrie Kosky, an Australian native who recently won England’s Laurence Olivier prize, has not only set out to change the ‘German-only’ policy starting next season but evoke the East Berlin house’s roots in operetta and the legacy of 1920s liberal culture, taking his own ethnic identity and sexual orientation as a case in point (“Will the ostentatious denotation ‘I’m Australian, Jewish and gay’ suffice as the motto for an Intendant?” quipped Manuel Brug in Die Welt).

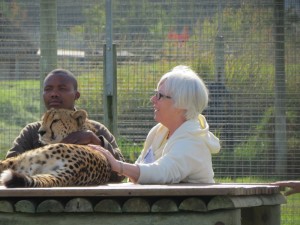

As fate would have it, the last premiere of the Homoki regime leaves Kosky with fertile ground to usher in a new ethos. Handel’s Xerxes, staged by the coveted Norwegian director Stefan Herheim in his Komische Oper debut, has won understandably glowing reviews across the board. Herheim’s production, seem May 19, takes a deceptively historical approach by setting the opera in its 1738 premiere at the Kings Theater, but the action jumps back and forth between painted naturalist sets (Heike Scheele) and an 18th-century backstage by virtue of a revolving platform, dissolving any sense of convention. The director calls the concept a “baroque Muppet show” in the program notes, playing with the existential levels of theater within theater and theater within life. At the end of the opera, the platform revolves fully to reveal the towering black walls of the Komische Oper’s actual backstage, with the chorus having shed their elaborate period costumes (Gesine Völlm) for their daily dress.

- A baroque feast of sets and costumes in Herheim’s ‘Xerxes’ @Forster/Komische Oper

Xerxes is a court intrigue set in 5th-century Persia about a rivalry between King Xerxes and his brother Arsamene for the hand of Romilda, daughter of the prince Ariodate. Meanwhile, Romilda’s sister Atlanta vies for Arsamene. Handel’s version is based on an anonymous revision of a libretto by Silvio Stampiglia. The original cast included the castrato Caffarelli in the title role and other stars of the day such as the soprano Elisabeth du Parc, known as ‘La Francescina,’ in the role of Romilda. Disguised ruses and falsely assigned love letters provide for some chaotic buffo moments, while the opera explores the more serious themes of true love, jealousy and fate. In this sense, as the program notes point out, the opera can be considered a kind of dramma giocoso—a genre which Mozart and Da Ponte would ultimately make immortal—although officially it is still opera seria.

Herheim takes a strictly comic approach, poking fun at the singular arrogance of the title character in both his role as a narcissistic king and as a castrato. Xerxes (Stella Doufexis) sings the opening aria “Ombra mai fu” and parts of other numbers in Italian while the rest of the opera, with the exception of one aria by Arsamene, is sung in German. When the king spits out “Perfido!” (Traitor!) to Prince Ariodate upon learning that he has married Romilda to Arsamene, the production effectively mocks the passionate drama of Italian opera. Xerxes not only calls the shots onstage but within the Komische Oper itself, descending into the pit with the crucial line “what you consider love is often only deception and appearance,” holding up a hand to stop the conductor (Konrad Jünghanel) before bringing the house to darkness with a snap.

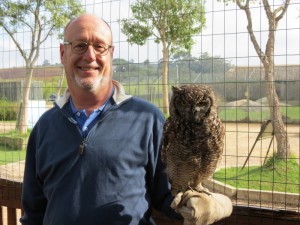

Stella Doufexis entertaining the audience as Xerxes @Forster/Komische Oper

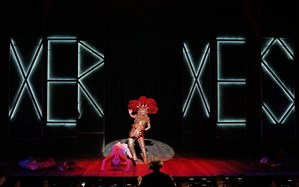

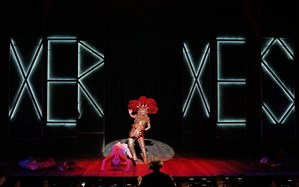

Other gestures are just for the sake of having some laughs. During Xerxes’ aria’ “Più che penso alle fiamme del core,” the set is dismantled to reveal cabaret-style lights reading “Xerxes” which are then rearranged to read “Sex Rex.” Doufexis points to the first word as she sings of her passionate flames, an adolescent touch that nevertheless seemed to delight the audience. The third scene features oversized dancing sheep who, while amusing at first, grow wearing as they began to interrupt the music with their ‘baas.’ Still, Völlm’s costumes are so authentic and well crafted—from these creatures to the gilded suits and towering plumed caps of Xerxes and his army to the chorus’ Rafael-like cherub fare—that it was easy to forgive the occasional relapse into directorial indulgence.

The cast was generally strong throughout, delivering punch lines with persuasive comic timing while maintaining high musical standards. Doufexis anchored the production with a velvety timbre, skillful dynamic nuance and a keen sense of Herheim’s highly complex stage concept. When she stepped toward the audience at the end of the opera, eyes widened as if emerging from a time machine, it was hard to suspend one’s disbelief. The mezzo Karolina Gumos was a charismatic, rich-voiced Arsamene, nailing her coloratura in the aria “Amor, tiranno Amor” in which she begs Xerxes to soften. The Swiss soprano Brigitte Geller brought the right touch of beguiling charm to the role of Romilda with a ripe lyric timbre, and Julia Giebel wielded her slightly underpowered soubrette to satisfactory effect as the pesky Atlanta. Katarina Bradic made for an even-voiced, desperate Amastre, and Dimitry Ivashchenko brought a resonant bass to the role of Ariodate. As the servant Elviro, the bass Hagen Matzeit made a stand-out performance in falsetto voice as a disguised flower vendor. Junghänel, an early music specialist, led the orchestra of the Komische Oper in an incisive but muscular account whose charged baroque expression at times compromised a sense of flowing legato, instead underscoring the sharp accents of the German language.

The Seven Deadly Sins

Kosky could hardly have chosen a stronger statement of his vision for the Komische Oper than with his new production of Kurt Weill’s Seven Deadly Sins, which premiered February 12 and returned this month. To be sure, his 2011 production of Rusalka featured gutted sea creatures and a German libretto that was too much to stomach for this reader, who once learned Czech and trekked all the way to Prague to hear Dvorak in its authentic setting (call me a purist). But with his latest undertaking, seen May 20, Kosky reveals an aesthetic restraint that is the antithesis of the slap-happy stagings which dominate the Berlin house. Weill’s Seven Deadly Sins was conceived with Bertold Brecht for Balanchine’s Paris company ‘Les Ballets 1933’ as a ballet chanté for the composer’s two-time wife Lotte Lenya and the dancer wife of the British impresario Edward James. The score seamlessly weaves together popular song, cantata, and dance music, while the text refers to a single protagonist, Anna, who has been sent on a voyage throughout the U.S. to earn money for a small house her family is building in Louisiana. She is accompanied by a hedonistic alter ego whom she refers to as her sister—also named Anna—as she dances and turns tricks along the way, learning the consequences of pride, lust, avarice and other sins. The work conveys an even more direct critique of capitalism than The Three Penny Opera, with a prescient understanding of the difficulties that the writers would face upon their imminent exile from Germany.

As a prelude to the work, Kosky inserts a selection of seven Weill songs ranging from Berlin im Licht (1938) to Wie lange noch? (1944). Dagmar Manzel, a well-known German actress, emerges slowly from behind closed curtains to join her pianist (Frank Schulte) in a straight cabaret delivery in which she is lit by a single spotlight. As if to foreshadow the desperation Kosky creates in Seven Deadly Sins, Manzel desperately tugs at the curtains during Youkali, a tango that describes a fictitious utopia, only to pull them back entirely to reveal the orchestra for the central work. As Manzel recounts her travels from Memphis to San Francisco with mounting hysteria, occasionally breaking out into deliberately ungraceful ballet, the male quartet representing Anna’s family sings from darkened balcony boxes above the stage. The most powerful tableau emerges in Los Angeles, where Manzel flap dances with a frozen expression of agony. While guilt-ridden allusions to the horrors of World War Two have become standard fare in Germany, Kosky’s understated, expressionist touch was shockingly relevant in the city whose avant-garde culture once helped breed one of the most powerful artistic collaborations in history.

Dagmar Manzel in Weill's 'Seven Deadly Sins' @Monika Rittershaus/Komische Oper

Kosky does go a bit over the top when Anna shrieks hysterically above her family’s moralist incantations, and the invented a capella epilogue about a drowned woman was far too morbid for the spirit of this resigned yet hopeful satire, not to mention that Manzel’s voice was audibly spent by this point. The singer otherwise gave a gripping performance with her smoky voice, generous presence and dry dramatic detachment. That she may be considered slightly too old for the role is justified by Kosky’s concept which casts the entire journey as a memory; in the end Manzel pinches the flesh on her arms as if unaware of how she had aged. The male quartet formed a musically solid ensemble, and Joska Lehtinen brought a ringing, slightly scolding tenor to the father’s aria about Anna’s greed. The orchestra provided fine accompaniment under Kristiina Poska, its Germanic sound culture providing weight to Weill’s forward-looking yet rigorous harmonic development and wistful melodies.