By James Jorden

One of the things I’m gradually learning as I’m coming up my the 20th anniversary of writing about opera for publication is that you have to be wary about making Pronouncements, because no matter how obvious or intuitive a hard-and-fast rule seems to be, if you write it down where people can find it, one of these days it’s going to embarrass you.

Who would have thought that when, ages ago, I penned something called Dr. Repertoire’s 10 Rules for Stage Directors, I would one day change my mind about not just any rule but Rule #1 (“DON’T STAGE THE OVERTURE, in all caps and bold font yet.)

Though, to be sure, I still feel like most attempts to stage the overture are pointless, as, for example, the silly dumbshow at the top of Le Comte Ory at the Met, by which Bartlett Sher accomplishes nothing but spoiling Comtesse Adèle’s actual entrance half an hour later, and banging up poor Pretty Yende’s knee when she stumbled over those rickety escape steps.

But it is possible, I admit it now, to stage the overture in meaningful and moving way, and the spectacle François Girard came up with for the beginning of the new Parsifal ended up being one of my favorite things among many in this really excellent productions.

The front curtain is a dark mirror, reflecting dimly the horseshoes of houselights of the Met auditorium. The music starts with the lights not quite completely out, and they continue to fade slowly as stage lights come up behind the transparent mirror drop. We see ranks of men in dark suits (close enough to formal wear as makes no difference) and women in little black dresses: an idealized “opera audience,” uniformly chic.

Now, this “mirror” trope—connoting “as you, the audience see yourselves reflected, so is our play meant to be about your own lives”—is quite a familiar one: Hal Prince’s Broadway production of Cabaret began with it way back in 1966, and more recently Robert Carsen adopted this coup de théâtre for his Don Giovanni to open La Scala in 2011.

But Girard took the idea a little further. First we noticed the distinctive curly head of Jonas Kaufmann’s Parsifal among all the swells: he seemed not quite sure where he was or why he was there. As the “pure fool” tried to make sense of the motionless ranks around him, they slowly began to move, as if the “performance” they were watching had finished perhaps (this is adeptly set to the c minor repetition of the opening theme.) The crowd slowly segregates into men in the front row and women toward the back, and then the men start removing costume pieces: shoes and socks, ties, jewelry, and finally jackets, until the chorus are in identical white shirts and black slacks.

Meanwhile the women cover their heads with veils and retreat slowly upstage right. The men also disperse, but they seem to have some purpose: they are arranging chairs into a tight circle, then sitting shoulder to shoulder in some sort of meditative state. Finally the lights come up and the mirror flies out to reveal a parched hillside bisected by a sliver of dried riverbed, as Gurnemanz appear over the hill on the “men’s” side of the cleft.

Now, this all I found subtle but impressive, or possibly even more impressive for its subtlety. The “cross fade” between the Met auditorium and the world onstage suggested that the action unfolding onstage was not strictly fiction but rather an alternative reality: a story about what might have happened or what might yet happen. Somehow the civilization we know so well, going to the opera and wearing ties and all of that, just might disappear over time, and what might be left would be this curious community founded on a form of religion that seems familiar enough in outline but not in detail.

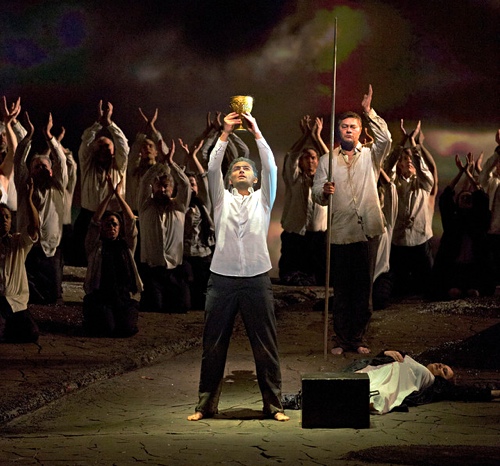

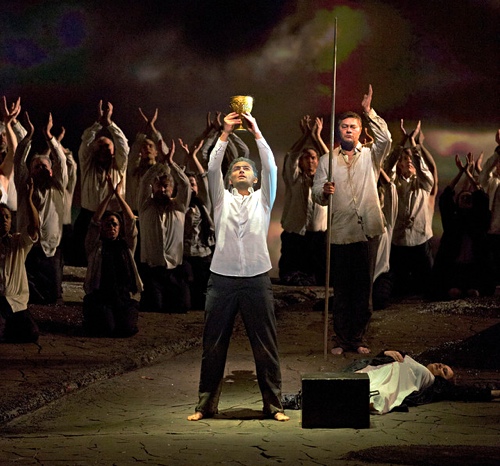

Now, after this point, the production veers in a slightly different direction. Girard takes the wound of Amfortas as his central metaphor: something once whole that is now torn apart. The dramatic progress, then, is toward restoration, reconciliation, repair.

We’ve seen the cleft separating the stage and the division between the sexes. But at the end of the first act comes a huge surprise that really rocked me back on my heels. Per the stage directions, Gurnemanz realizes (or anyway assumed) that Parsifal found the Grail ceremony meaningless, so he angrily expels him from the hall. In this production, of course, there is no hall per se, just an area on the hillside where the faithful gather. But even so, I was expecting Gurnemanz to send Parsifal on his way, over the hill or whatever. That’s not what happens, though.

Instead, Gurnemanz walks away, leaving Parsifal alone. The Stimme (aus der Höhe) intones

“Durch Mitleid wissend,

der reine Tor!”

… but maybe the voice isn’t coming from the heights after all. The cleft in the ground gradually opens further into a chasm, and Parsifal crawls over and peers into the depths. Is that, perhaps, where the voice is coming from: inside the wounded earth, and, instead of a prophecy, perhaps these words are a call to further adventures?

That does seem to be the case as the second act starts. It takes a few minutes to get one’s bearings, but eventually the image becomes clear. That vertical slit at the back of the stage is not, as it first appeared in early press photographs, an obvious vaginal symbol, but rather the other side of the “wound” in the earth, rotated through 90 degrees. Inside the wound, naturally, is freely-flowing blood, though, perhaps not quite so naturally, there are a legion of white-gowned brunette maidens grasping silver spears, all surrounding Klingsor in his blood-soaked business suit.

This is an intriguing idea: Parsifal is eventually going to heal this wound, but first he must explore the inside of it, brave all the evils and temptations that have so gravely injured poor Amfortas. I was reminded idly of the sci-fi film Fantastic Voyage. (In fact, some of the projections for this act by Peter Flaherty resemble the special effects for that 1966 movie: giant corpuscles throbbing in slow motion and so forth.)

So the tone of the second act is not that of a standard Parsifal. There’s less of a sense of personal connection between Parsifal and Kundry, and more of a sort of trial or test, perhaps a reenactment of Amfortas’s experience. If that is so, it is a successful examination: Parsifal comes to the point at which Amfortas made his mistake, forgetting himself in the ecstasy of sexual attraction, but he suddenly returns to himself. Significantly, this “return” is not accomplished by any intellectual application of rules of morality or behavior, or even by any questioning process, but rather through a sudden intuitive empathy for Amfortas’s experience.

But that intuitive breakthrough is not a cure, only a sign pointing to the cure. There are numerous wounds, both literal and metaphorical, to be closed in order to make the system whole again, and so Parsifal must experience a lifetime of empathy in all its forms in order to be able to understand how to bring the divorced parts together again.

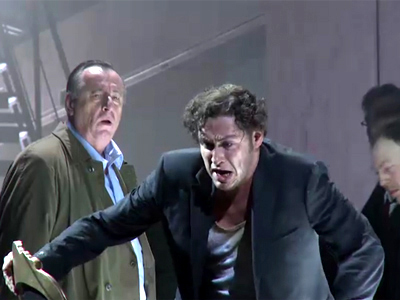

Here again, as Parsifal returned in the third act, I was confused: what I expected from previous exposures to the work was a kind of exalted hero, someone imbued with the holy energy of enlightenment. Even in the strange and violent production by Calixto Bieito, that’s how Andrew Richards played it.

In Girard’s interpretation, Jonas Kaufmann took almost precisely the opposite approach. He was broken down by fatigue on his entrance (as all Parsifals are) but he never got that burst of divine oomph, that “now I am a savior!” moment. At most he achieved a kind of basic peace, enervated in body but maybe a little clearer in mind. There was nothing you could call joy or exaltation in his taking on the office of king of the grail; rather, it was a simply quiet duty, something one does without any particular pleasure, but something that absolutely must be done. Nothing glamorous or glorious, but rather a responsibility: the work of an adult.

And the work is accomplished, or at least well begun: the wound of Amfortas is healed, the sexes mix naturally, and the Grail is available to anyone who seeks it, unhidden, uncovered and open. Even the complicated question of Kundry’s unnatural existence is resolved, quietly and with dignity. (I thought I would never see a staging of this piece in which Kundry actually dies as prescribed in the stage directions, but without the unwanted sense that she is somehow being punished. Girard directs this moment with great elegance, assigning Gurnemanz and Parsifal to attend to her last peaceful moments. Her death feels natural and organic, an end to suffering, which is exactly as it should be.)

But, again, there’s nothing triumphant here, no sense of “winning.” The task of healing the world’s wound is accomplished not through any magic or feel-good religion, but through the dirty, grueling grind of endurance, living day by day as best one can. The earth is still parched, the sky still dark. This Parsifal, chosen one or not, has to earn his crown again with every new day.

Photos by Ken Howard, except for Andrew Richards as Parsifal (Martin Sigmund)

legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com

legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com