By ANDREW POWELL

Published: April 9, 2014

MUNICH — Not a week goes by here now without media mention of Valery Gergiev. The musical friend of Vladimir Putin and, more to the point, high-profile employee-to-be of the City of Munich inspires comment even in modest suburban newspapers. Many want his alarmingly long contract (2015–20) shredded.

But the Russian maestro was already a rotten choice as Chefdirigent of the tax-payer-funded, city-run Munich Philharmonic before Putin upset Pink List politicians over human rights and the Green Party over Crimea.

His repertory limitations, his work habits and his first loyalties all portend a discordant, creatively stunted tenure during which Munich, despite its €800,000-a-year* wage, has no hope of being the artist’s top priority. If not shredded, the contract of Feb. 2013 should certainly be adjusted.

Gergiev is globally known from his base at St Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theater, where he operates a network of répétiteurs and conducting assistants who extend brand “Gergiev” beyond the physical and temporal limits of one person.

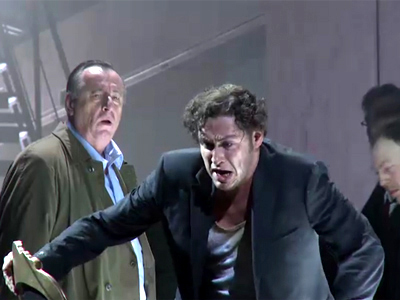

Seven days ago, for instance, he entered a principal guest conductor agreement (pictured) with Astana Opera, the expensively housed company of Nursultan Nazarbayev in the flat and flashy Kazakh capital.

Munich’s old and Astana’s new money follows Gergiev earnings at the London Symphony Orchestra, where his stint as principal conductor (2007–15) resembles good preparation for the job here.

But London’s one-night, one-program pattern suits the Russian’s lickety-split scheduling better than Munich’s (American-style) weekly program iterations. Example: he is this week able to dart to New York for a Strauss concert between two different LSO Scriabin programs three days apart.

As one MPhil insider earnestly phrased it last December, peripatetic Gergiev “must reinvent himself” so that he can stay in one place, with one program and one group of musicians, for a whole workweek, build partnerships through rehearsals he himself leads, and mine the interpretive depths.

Good luck with that. And the reinventing would need to extend to repertory: Munich concertgoers enjoy their Slavic diversions but expect passionate leadership in Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner. Alas, in 25 years as a star, Gergiev has acquired no reputation in these composers. Ditto for Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, Schumann and Mendelssohn.

“It’s political,” everyone says, when asked why Gergiev was chosen. They mean he was chosen by city politicians — not friends of Putin, of course, but people whose collective knowledge and consensus thinking permit little beyond the purchase of a big name, which Gergiev undeniably is.

In their wisdom, in 2009, they “lost” the MPhil’s hot-property Generalmusikdirektor Christian Thielemann, and followed up in 2010 by replacing him with the jaded Lorin Maazel (for 2012–15). Decline has followed.

The politicians do not decide unaided, however. A consulting board called the Philharmonische Rat liaises between the orchestra’s Intendant Paul Müller and Munich’s city council, which approves budgets and major contracts. The Rat includes councilors, orchestra members, Müller, and Hans-Georg Küppers, the city’s Kulturreferent. If nothing else, processes are peaceful. The recent difficulties in Minneapolis and San Diego cannot be imagined here.

Ironically, while Rat members can speak freely, Gergiev is expected to constrain his speech — not weigh in on matters like Crimea that needn’t concern a Moscow-born Ossetian based in St Petersburg — and acquire the diplomatic tact of a City of Munich employee, a world-roaming cultural ambassador whose every move and view will reflect on Munich, Bavaria and Germany.

Predictably he hasn’t. By hailing the Crimea change, even in his current status as an MPhil guest, he may have done more to curtail his Munich future than any problem of scheduling or repertory weakness could have.

The Green Party on Mar. 27 forced instructions to Küppers and Müller: chat with the maestro during his next visit, bitte, and illuminate the boundary between free speech and employee discretion.

They can try. Gergiev is in town next month with his beloved Mariinsky Orchestra. More productive, though, would be a chat that dilutes the publicly signed Chefdirigent deal into a guesting plan like Astana’s. Time remains on Maazel’s contract to research and court a more suitable replacement, allowing Gergiev to remain Gergiev, and Munich to savor the scores he leads best. Without the negative attention.

[*The salary reportedly paid to Christian Thielemann, whose title indicated a slightly loftier position. The incumbent, Lorin Maazel, is Chefdirigent, as was James Levine before Thielemann.]

Photo © Astana Opera

Related posts:

Jansons! Petrenko! Gergiev!

Gergiev Undissuaded

Maestro, 62, Outruns Players

Concert Hall Design Chosen

Stravinsky On Autopilot

Gergiev, Munich’s Mistake

Wednesday, April 9th, 2014By ANDREW POWELL

Published: April 9, 2014

MUNICH — Not a week goes by here now without media mention of Valery Gergiev. The musical friend of Vladimir Putin and, more to the point, high-profile employee-to-be of the City of Munich inspires comment even in modest suburban newspapers. Many want his alarmingly long contract (2015–20) shredded.

But the Russian maestro was already a rotten choice as Chefdirigent of the tax-payer-funded, city-run Munich Philharmonic before Putin upset Pink List politicians over human rights and the Green Party over Crimea.

His repertory limitations, his work habits and his first loyalties all portend a discordant, creatively stunted tenure during which Munich, despite its €800,000-a-year* wage, has no hope of being the artist’s top priority. If not shredded, the contract of Feb. 2013 should certainly be adjusted.

Gergiev is globally known from his base at St Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theater, where he operates a network of répétiteurs and conducting assistants who extend brand “Gergiev” beyond the physical and temporal limits of one person.

Seven days ago, for instance, he entered a principal guest conductor agreement (pictured) with Astana Opera, the expensively housed company of Nursultan Nazarbayev in the flat and flashy Kazakh capital.

Munich’s old and Astana’s new money follows Gergiev earnings at the London Symphony Orchestra, where his stint as principal conductor (2007–15) resembles good preparation for the job here.

But London’s one-night, one-program pattern suits the Russian’s lickety-split scheduling better than Munich’s (American-style) weekly program iterations. Example: he is this week able to dart to New York for a Strauss concert between two different LSO Scriabin programs three days apart.

As one MPhil insider earnestly phrased it last December, peripatetic Gergiev “must reinvent himself” so that he can stay in one place, with one program and one group of musicians, for a whole workweek, build partnerships through rehearsals he himself leads, and mine the interpretive depths.

Good luck with that. And the reinventing would need to extend to repertory: Munich concertgoers enjoy their Slavic diversions but expect passionate leadership in Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner. Alas, in 25 years as a star, Gergiev has acquired no reputation in these composers. Ditto for Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, Schumann and Mendelssohn.

“It’s political,” everyone says, when asked why Gergiev was chosen. They mean he was chosen by city politicians — not friends of Putin, of course, but people whose collective knowledge and consensus thinking permit little beyond the purchase of a big name, which Gergiev undeniably is.

In their wisdom, in 2009, they “lost” the MPhil’s hot-property Generalmusikdirektor Christian Thielemann, and followed up in 2010 by replacing him with the jaded Lorin Maazel (for 2012–15). Decline has followed.

The politicians do not decide unaided, however. A consulting board called the Philharmonische Rat liaises between the orchestra’s Intendant Paul Müller and Munich’s city council, which approves budgets and major contracts. The Rat includes councilors, orchestra members, Müller, and Hans-Georg Küppers, the city’s Kulturreferent. If nothing else, processes are peaceful. The recent difficulties in Minneapolis and San Diego cannot be imagined here.

Ironically, while Rat members can speak freely, Gergiev is expected to constrain his speech — not weigh in on matters like Crimea that needn’t concern a Moscow-born Ossetian based in St Petersburg — and acquire the diplomatic tact of a City of Munich employee, a world-roaming cultural ambassador whose every move and view will reflect on Munich, Bavaria and Germany.

Predictably he hasn’t. By hailing the Crimea change, even in his current status as an MPhil guest, he may have done more to curtail his Munich future than any problem of scheduling or repertory weakness could have.

The Green Party on Mar. 27 forced instructions to Küppers and Müller: chat with the maestro during his next visit, bitte, and illuminate the boundary between free speech and employee discretion.

They can try. Gergiev is in town next month with his beloved Mariinsky Orchestra. More productive, though, would be a chat that dilutes the publicly signed Chefdirigent deal into a guesting plan like Astana’s. Time remains on Maazel’s contract to research and court a more suitable replacement, allowing Gergiev to remain Gergiev, and Munich to savor the scores he leads best. Without the negative attention.

[*The salary reportedly paid to Christian Thielemann, whose title indicated a slightly loftier position. The incumbent, Lorin Maazel, is Chefdirigent, as was James Levine before Thielemann.]

Photo © Astana Opera

Related posts:

Jansons! Petrenko! Gergiev!

Gergiev Undissuaded

Maestro, 62, Outruns Players

Concert Hall Design Chosen

Stravinsky On Autopilot

Tags:Astana Opera, Christian Thielemann, Commentary, Green Party, Hans-Georg Küppers, London Symphony Orchestra, Lorin Maazel, Mariinsky Orchestra, Mariinsky Theater, München, Münchner Philharmoniker, Munich, Munich Philharmonic, Nursultan Nazarbayev, Paul Müller, Pink List, St Petersburg, Valery Gergiev, Vladimir Putin

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed