By ANDREW POWELL

Published: December 22, 2013

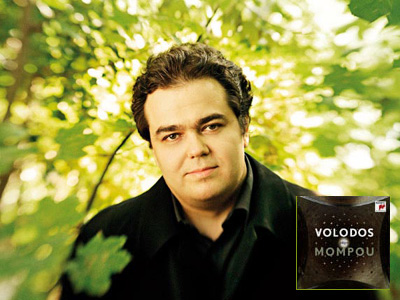

MUNICH — Somewhere between the patent introspection of his new Mompou CD* and the tags of his early Stateside career — “big bravura pianist,” “new Horowitz” — lies an accurate description of Arcadi Volodos. It may simply be this: German Romantic, as in Schumann and Brahms, with impressionist flair.

That was the take, anyway, from a commanding, technically flawless Bell’Arte recital Dec. 12 here at the Prinz-Regenten-Theater, and it is buoyed by the disc. The 41-year-old pianist from St Petersburg stands distant from the trajectory of his rise: 1998 Carnegie Hall debut, Berlin readings of Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky concertos (1999 and 2002). He still plays with strength and vision, but what distinguishes him now is a command of form and the willingness to disturb it in expressive ways.

Stardom, meanwhile, has improbably blurred thanks to the presence of another St Petersburg pianist with what trademark authorities might term a confusingly similar name, Alexei Volodin, 36. (No also-ran, the latter gave a recital himself Dec. 15 at the Mariinsky.) Even so, allegiance to Volodos has held firm, particularly here in Germany, and to its credit his record label Sony Classical has stayed with him.

Schubert’s 1815 C-Major Sonata opened the recital, stitched up with its Allegretto (D279/D346). It seemed a weak choice until Volodos testily hammered and carved his way through, knowing exactly what he wanted from the music. We heard the sound of Beethoven.

The pianist stressed formal commonalities in the standalone pieces of Brahms’s Opus 118 (1893) and allowed contrasts to make their point without emphasis. Full, deep tone colors throughout, and natural lyricism in the framing sections of the A-Major Intermezzo and in the Romance, lent due character. In the final measures of the E-flat-Minor Intermezzo, as poetic cap, Volodos mustered a monumental stillness. (His reported recent success in Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto, with longtime collaborator Riccardo Chailly, is consistent.)

After the break and a fluent Schumann Kinderszenen, Volodos boldly energized the same composer’s C-Major Fantasie (both 1838), its three movements speaking with phenomenal power and passionate unity. For the Finale (Langsam getragen, durchweg leise zu halten), he coaxed a mood of poignant reflection unmatched even by Pollini in the famous 1973 recording (made across town here at the Herkulessaal).

The CD* of miniatures by Federico Mompou (1893–1987), recorded last December in Berlin, is a worthy issue in these times of superfluity. Few distinguished recordings have been made of the Spaniard’s music, and Volodos commits himself intensely to it, judging from his liner essay as well as his playing. Although the output is often related to Satie, Mompou’s late imaginative world (not the style) lies closer to Debussy in his Préludes.

Volodos declares the four Música callada sets (1951, 1962, 1965, 1967) to be peaks of achievement: “ … the music [Mompou] spent all his life moving towards … wrested from eternity, as if it already existed in the Spheres … .” He plays eleven of the pieces, from the total of 28, drawing on all four sets in a sequence his own. This “quietened music” is both abstract and personal, the product of an old solitary man, but not one at death’s door; Mompou lived another twenty years after completing Set 4. Many pieces are “Lento,” a marking that satisfies the composer for divergent exercises in peace (VI), pain and emptiness (XXI), and generalized remoteness or stillness. Others, such as the Moderato XXIV of 1967, flow so plainly and concisely that a marking is hardly needed. The many chilly passages in the Música callada tend to be broken by warm chords in unexpected places.

Volodos revels in the myriad nuances of these valued miniatures and, as in Brahms, downplays contrasts in favor of coherence. He finds fantasy here and there, catches the fleeting moments of excitement, and instantly lets ideas go when they must. The interpretations are light of touch and magical.

Half of the disc holds short independent works, most of them tellingly shaped. In Preludio 12 (1960) and elsewhere, Volodos shows Vlado Perlemuter’s knack for placing just the right weightings in pale adjacent phrases to support a long idea, saving music that could easily sound aimless. The much earlier (1918) Scènes d’enfants suite, home of the cute encore Jeunes filles au jardin, receives an imaginative traversal. Sony’s release is strikingly packaged with photographic details of Antonio Gaudí buildings in Barcelona, the composer’s home town, although typos mar its booklet. The company might now want to entice Volodos into documenting the remaining Música callada.

[*In August 2014 the disc received an Echo Klassik Award.]

Photo © Sony Music Entertainment

Related posts:

Pogorelich Soldiers On

Nazi Document Center Opens

Levit Plays Elmau

Arcanto: One Piece at a Time

Carydis Woos Bamberg

Brahms Days in Tutzing

Thursday, November 8th, 2012By ANDREW POWELL

Published: November 8, 2012

MUNICH — Johannes Brahms came here in 1870, catching the completed half of Wagner’s Ring and hobnobbing with colleagues, Liszt among them. He basked in new celebrity, his German Requiem having appeared in print a year earlier. The visit ended with a few days’ repose at Lake Würm, nearby.

He came again three years later. Der Ring remained incomplete, but in any case he sought other things: a meeting with poet Paul Heyse, guidance on writing for orchestra from conductor Hermann Levi (whose brother ran his asset portfolio), and more time at the deep tranquil lake (pictured), with its southward vistas to the Alps. Levi duly helped in the city, and the composer checked in in May for a four-month lakeside stay in the fishing village of Tutzing, lately reachable from downtown by train.

Brahms: “Tutzing is prettier than recently imagined … . The lake is usually blue, but a deeper blue than the sky … also the chain of snowy mountains — one cannot stop looking at them.”

Tutzingers take pride in this Brahms connection. It produced the Haydn Variations and gave life to the two long-stalled, minor-key string quartets. At a stretch, you could say the sojourn nudged Brahms over thresholds in both his orchestral and chamber music. It saw too the premiere of the Acht Lieder und Gesänge, Opus 59.

Settled in the 6th century by families called Tozzi and Tuzzo, Tutzing sports a lakeshore Brahms promenade, a Brahms memorial, a Brahms apothecary and, not so inevitably, a Brahms festival.

This last, dubbed Tutzinger Brahmstage, had an abortive start in the 1950s on the initiative of anti-Semite and “pronounced National Socialist” pianist Elly Ney. Later, much later, artist manager Christian Lange put the festival on an annual fall footing with modest strata of local government support. Sometime in between, Lake Würm officially became “Lake Starnberg.”

But music festival visitors to handsome Tutzing face a number of ponderables. A walk of homage along the spectacular promenade, for instance, finds the composer honored in flat stone between lake and Alpine view benches, a pleasing effect until you turn and see, lurking just feet away, a grand memorial to the Nazi pianist with high bronze bust and trellised garden.

Choosing when to visit confronts the problem of five events spread around three weekends, not the Ojai-like “days” timeframe suggested by the festival name. (A Carl Orff Festival in the next municipality, where that composer is buried, does better in this regard and supports its local hotels.)

Then there is the matter of programming. Tutzinger Brahmstage 2012, which has just ended amid blazes of fall color and a run of blue skies, favored rings around the composer in place of any survey. Mostly Brahms it was not. Brahms and jazz (a concert on Oct. 18) go together like Mahler and reggae. The lone string chamber work offered, the G-Major Sextet (Oct. 14), got lumped with an unneeded reduction for the same forces of Beethoven’s Pastorale Symphony. Baritone Michael Volle diluted his Liederabend (Oct. 21) with warhorses of Mahler, lessening the time to explore Brahms’s vaster output for voice.

On Oct. 26, though, festive impulses and programming logic coalesced nicely. Someone had recalled that Brahms wrote organ music and had invited Vienna-based Renate Sperger to play the 3,000-pipe, 28-year-old Sandtner organ of Tutzing’s neo-Baroque St Joseph’s Church, an instrument with ripe sound and tight, unobtrusive action.

Her program contrasted Johann Nepomuk David’s quasi-cartoonish 1947 Partita on Es ist ein Schnitter, improbably a heartfelt tribute to a friend he lost in combat, with a row of Brahms chorale preludes. Six of these, concluding with O Welt, ich muß dich lassen, were from Opus 122, the chiseled and ashen collection penned a year before the composer died. At midpoint came Brahms’s early but resolute Prelude and Fugue in A Minor, WoO 9 (1856), while two Bach staples — the Fantasia and Fugue in G Minor, BWV 542, and the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, BWV 565 — framed the evening.

Sperger traced the excesses of the David with calm efficiency and savored introspection in the chorale preludes, abetted by Sandtner’s suave apparatus. In the Bach pairings, she wrought requisite thunder and scaled the quilted fugal flights with unbroken legerdemain.

On the evidence of this year, Tutzinger Brahmstage holds potential in reserve, not least for local businesses. Brahms’s music, particularly the vocal and chamber scores, suits an intimate meeting place, and Tutzing has an authentic claim as a host town, with viable concert venues in St Joseph’s Church and the Evangelische Akademie, its idyllically sited former palace. A focused few days and a sculptural clean-up on the promenade could work wonders.

After leaving Tutzing and Munich in 1873, Brahms returned home to Vienna. There he led the Philharmonic in the November premiere of the Haydn Variations, an orchestral triumph from which he never looked back.

The next month he was once more in Bavaria, to pick up mad King Ludwig II’s Maximilian Medal for Art and Science. Wagner got his at the same time. Who knew? Perhaps Ludwig thought equally highly of both of them.

Photo © Tourismusverband Fünf-Seen-Land

Related posts:

Tutzing Returns to Brahms

A Stirring Evening (and Music)

Kaufmann, Wife Separate

Zimerman Plays Munich

Widmann’s Opera Babylon

Tags:Brahms, Brahms Days, Brahmstage, Christian Lange, Commentary, Elly Ney, Evangelische Akademie, Haydn Variations, Hermann Levi, Johann Nepomuk David, King Ludwig II, Lake Starnberg, Michael Volle, München, Munich, Nazi Germany, Renate Sperger, Review, Schloß Tutzing, Tutzing

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed