By Rebecca Schmid

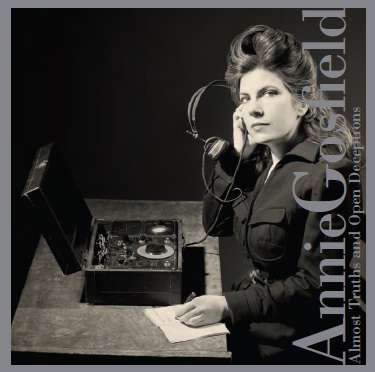

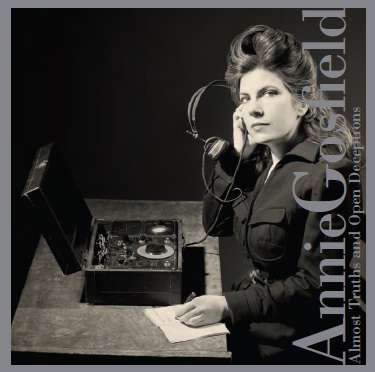

The New York-based composer Annie Gosfield is best known for her synthesis of industrial sounds and other unconventional sampling into rock-inflected, yet often intricately wrought, compositions. As a fellow at the American Academy in Berlin last semester, she researched encrypted radio broadcasts from World War Two—part of a long-standing fascination with archaic technology and its unusual sounds—for a new violin work that will premiere at the Gaudemaus Muziekweek in the Netherlands this September. Satellite transmissions, the clanking of junkyard metal, factory machinery, destroyed pianos, and detuned radios have all been repurposed in Gosfield’s repertory, to often surprisingly lyrical effect. Underlying many of these explorations is a highly personal thread. “Daughters of the Industrial Revolution” (2011), the most recent work on her upcoming album, Almost Truths and Open Deceptions, was inspired by her grandparents’ experience as immigrant workers on the Lower East Side. “I am a third generation daughter of the industrial revolution,” she writes in program notes, “linked to this history, not only genetically and geographically, but as a composer who often uses raw materials and transforms them into something new.”

The assembly-line rhythms, sampled from a factory in Nuremburg, unshackled electric guitar, ringing sampler melody and percussion in the approximately five-minute excerpt from this work create a punk rock-like fare that contrasts sharply with the album’s title work, a chamber concerto with a cello part written for Felix Fan at its center. The title “Almost Truths and Open Deceptions” refers to the movement of the entire ensemble toward “a mass of open D strings,” as Gosfield explains. At the end of the 24-minute work, the instruments settle through wilting glissandos into a decaying unison that fades ghostlike. The concerto opens with brash string attacks, wild circling motives and pulsing forward motion that settles down deceitfully, foreshadowing the piece’s conclusion, before ceding to a cello that implores and groans. Intimate, folky exchanges between the piano, violin, and cello ensue in the course of the work’s impending movement, propelled through variegated rhythms and animated melodic writing, with a percussive interlude that teases the listener as much as it creates suspense.

‘Almost truths’ would also seem to apply to the album’s first track, “Wild Pitch” (2004), with its double-entendre in reference to “a baseball game gone mad” as well as the musical sense of the word. Fan again takes center stage along with the members of his trio “Real Quiet,” scraping out both tuned and quarter-toned figures against eerie piano (Andrew Russo), also played from the inside with a steel guitar slide among other objects, and high strung percussion (David Cossin). The excitability yields intermittently to meditative stasis, given an authentic flair with Chinese cymbals and broken gongs. Gosfield’s ability to foreground and manipulate pure instrumental sounds emerges even more clearly in “Cranks and Cactus Needles” (2000), inspired by the sounds of the now obsolete 78 RPM records and commissioned by the Stockholm-based ensemble The Pearls Before Swine Experience. Ripping, scratchy timbres in the strings evoke a record player on its last legs, while flute and piano play unaffected. Gosfield herself takes the keyboard for “Phantom Shakedown,” composed specifically for the album in 2010, over cosmic whirring, satellite bleeps, detuned piano, and machine rhythms, the piano’s heavy, if at time monotonous, chords moving through the samples as if drifting through a tunnel.

Some subtleties in the frequencies of the samples may not be as palpable on recording as they are live, yet instrumental balance is generally well-struck throughout the album. The first minutes of the title track are excessively loud at first hearing, but upon grasping the music’s structural strains becomes an absorbing listen. The detoned shades of “Cranks and Cactus Needles” manage to carry through effectively, the keyboard deliberately raucous beneath ripping strings. Roger Kleier’s electric guitar grinds organically with the machine riffs in “Daughters of the Revolution,” while the technical and expressive range of Fan’s cello, featured in four of six tracks, provides visceral continuity throughout the spectrum of Gosfield’s endeavors. David Cossin’s percussion provides a full range of timbral variety and rhythmic energy, fueling this music’s appetite for lyrical noise.

‘Almost Truths and Open Deceptions’ is out Aug.28 on Tzadik Records and can be pre-ordered on Amazon.com.

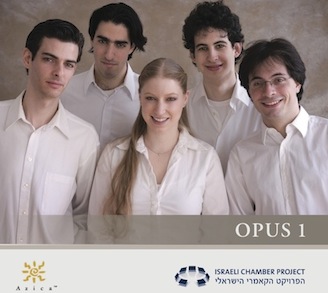

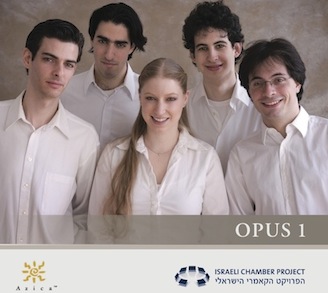

Opus 1

At a time when young musicians are grappling with the demands of audience development and changing business models, the Israeli Chamber Project (ICP) has created a flexible format that combines high quality performance and outreach into a single mission. Founded four seasons ago by young musicians based in New York, Berlin and Tel Aviv—most of whom graduated from Juilliard or the Manhattan School of Music—the octet divides its time between the concert hall and educational tours to rural parts of Israel, some of which are mostly Arab, that have little or no exposure to classical music. “It’s a response to a social-economic situation where there’s a kind of brain drain,” explains pianist Assaff Weisman, who also serves as the group’s executive director. “No one is left to teach there.” In turn, the chamber music society hopes to bring something of its native musical culture abroad, championing emerging Israeli composers and including pre-concert demonstrations. The ensemble, with two pianists, a clarinetist, and a harpist alongside a quartet of string players, can expand or shrink to suit a wide range of repertoire and has won praise for its inventive programming. The group’s debut album Opus 1 features an originally-commissioned quartet by the Berlin-based composer Matan Porat alongside duets, trios and a sextet.

The selection gives equal measure to late French Romaticism and Eastern European modernism, providing a fitting stylistic context for Porat’s Night Horses (2007). Dreamy piano arpeggios and rhapsodic lines in the clarinet over nearly imperceptible slides and tremoli in the strings yield to tangled melodies that deliberately evoke Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps, as liner notes by Laurie Shulman explain. The work was originally inspired by an eponymous lecture by Jorge Luis Borges about the ‘nightmare’ as a ‘night horse’ that invades the psyche. The second movement features moaning strings and emphatic interlocking melodies that seem desperate to escape as the piano gallops along until a soft, waking clarinet melody resolves the emotional turmoil. Martinu’s Musique de Chambre No.1, scored for clarinet, harp, piano and string trio, provides the ensemble with another outlet for vibrant, free-ranging yet highly idiomatic musicianship. Folk rhythms emerge spontaneously alongside neo-impressionist elements, while the mysterious timbre and meditative stasis of in the inner Andante movement underscores the music’s unusual instrumentation.

Bartok’s Contrasts for violin, clarinet and piano, the only chamber work in which the composer involved a wind player, also features a slow-fast rhapsodic structure with a Pihenö (Relaxation) inner movement. The late Bartokian fare can barely contain its energy in the final movement as both violinist and clarinetist respectively alternate between two instruments, a detuned fiddle adding a searing touch of nostalgia. The album is balanced with the soothing mood of duets according special prominence to the harp. ICP harpist Sivan Magen performs in his own arrangement of Debussy’s Sonata for Cello and Piano, originally written in the composer’s last years after a spell of paralyzing depression. The harp’s dry, rippling timbre is not so convincing in the accompanying chords of the Prologue or the aggressive plucks that bring the final movement to a close but achieves a more compelling blend in the inner Sérénade. The Fantaisie for Violin and Harp of Saint-Saens, who as the liner notes explain was one of the few pianist-composers to write idiomatically for the harp, demonstrates a more conventional, and ultimately more consistently pleasing, use of texture.

The members of the ICP perform with youthful energy and polished, expressive musicianship throughout the album. Magen reveals his mastery of the instrument in French repertoire and blends skillfully in Martinu’s Chamber Music No.1. Weisman anchors the ensemble sensitively in Porat’s Night Horses, while clarinetist and ICP Artistic Director Tibi Cziger nails the dance motives of the opening Verbunkos movement to Bartok’s Contrasts. The performance of this work stands out for its crisp, lively rhythms and effortless sense of structure. Violinist Itamar Zorman, winner of the 2011 Tchaikovsky Competition, also impresses in the thorny harmonics of the final movement. Balance problems between the contrasting timbres of the instruments emerge only in the Porat, where subtle violin timbres in the opening do not come through audibly enough. Such are the perils of recording contemporary music, although audio engineering could perhaps artificially address the problem. All considerations aside, ICP’s fresh approach to chamber music breathes life into an art form whose myriad possibilities often go underappreciated in mainstream classical music life.

Opus 1 is already available for download and will be released on Azica Records July 31.

legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com

legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com

Can Newspapers Charge To Quote Reviews??

Wednesday, August 8th, 2012By Brian Taylor Goldstein

Dear Law & Disorder:

I recently came across the website of an artist management agency in Europe where they had posted the following: “The press review is temporarily not available. German newspapers Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and Süddeutsche Zeitung recently started to pursue institutions and artists using texts (press reviews, interviews, commentaries etc.) published by those newspapers on their websites or in any other commercial context without having paid for them. We have been advised to remove all press quotations from our website as the same phenomenon seems to happen in other countries like Switzerland and Austria.” Is this a copyright trend that will spread to other European countries and the USA? Will agents, and artists have to start paying for the use of (press reviews, interviews, commentaries) used to promote an artists career? Also, if an American agency has press reviews, interviews, commentaries from Europeans newspapers on their websites, such as from the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and Süddeutsche Zeitung, will these agencies be liable for payment of the use for this information, as well, as it is being used in a commercial context? (Thank you for your column on Musical America, and I also thank Ms. Challener for her leadership in including such information in the weekly email Musical America updates.)

Newspapers and magazines have always owned the exclusive rights to the articles, reviews, editorials, and interviews they publish. Just like you can’t make copies of sheet music, CDs, books, and other copyrighted materials, you cannot make copies of articles and reviews and re-post them without the owner’s permission. Even if you are not “re-selling” an article or review, anything that is used to promote, advertise, or sell a product or service (ie: an artist!) is a “commercial” use.” While “quoting” or “excerpting” a positive review is most often considered a limited “fair use”, making copies of the entire article or review is not. While it should go without saying, you also cannot “edit” or revise articles and reviews in an effort to make a bad review sound more positive. (That’s not only copyright infringement, but violates a number of other laws as well!)

The website you encountered was in response to certain German newspapers, in particular, who began making significant efforts to require anyone who wanted to copy or quote their articles or reviews to pay a licensing fee. In the United States, for the most part, most newspapers and magazines have not actively pursued agents or managers who have quoted articles and reviews on their websites to promote their artists. However, I am aware of managers and agents who have been contacted by certain publications where entire articles have been copied and made available for download. In such cases, the publication has demanded that the copy either be licensed or removed. I also know of agents and managers who have posted unlicensed images on their websites and then been contacted by the photographers demanding licensing fees.

As for the ability of an American agent to quote or copy articles from the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and Süddeutsche Zeitung, under the applicable international copyright treaties, they could require American agents to pay as well. While I don’t necessarily see this becoming a trend among US publications, its certainly worthwhile to reflect that anytime an agent, manager, or presenter uses images, articles, videos, other materials to promote an artist or performance, there are copyright and licensing considerations that need to be taken into consideration.

________________________________________________________________

For additional information and resources on this and other legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com

legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com

To ask your own question, write to lawanddisorder@musicalamerica.org.

All questions on any topic related to legal and business issues will be welcome. However, please post only general questions or hypotheticals. GG Arts Law reserves the right to alter, edit or, amend questions to focus on specific issues or to avoid names, circumstances, or any information that could be used to identify or embarrass a specific individual or organization. All questions will be posted anonymously.

__________________________________________________________________

THE OFFICIAL DISCLAIMER:

THIS IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE!

The purpose of this blog is to provide general advice and guidance, not legal advice. Please consult with an attorney familiar with your specific circumstances, facts, challenges, medications, psychiatric disorders, past-lives, karmic debt, and anything else that may impact your situation before drawing any conclusions, deciding upon a course of action, sending a nasty email, filing a lawsuit, or doing anything rash!

Tags:agent, artist, Brian Taylor, cannot make copies, commentaries, commercial context, copy, copyright, copyright infringement, european countries, Goldstein, license, Licensing, manager, permission, photograph, quotations

Posted in Artist Management, Arts Management, Copyrights, Law and Disorder: Performing Arts Division, Licensing | Comments Closed