By Rachel Straus

Which came first, the arcade game Pac-Man or Mechanical Organ by Alwin Nikolais? Both came into being in 1980. With a child-like glee, both present an abstracted technicolor figure, fearsomely navigating every which way. Moreover, after watching the Alwin Nikolais Celebration at The Joyce Theater (Feb. 9), it became clear that the late choreographer (1910-1983) influenced more than the world of dance. In Nikolais’ productions, technology drove his visions. Like a Steve Jobs of the theater, Nikolais was a master mind. He conceived the concept and aesthetic of each work by controlling all the elements: composition of the electronic score, costuming of his dancers, décor creation, and choreography (albeit in collaboration with his zealous performers, who worked with him at the Henry Street Playhouse).

Nikolais wasn’t just a prescient choreographer because of his employment of technology, he was a harbinger of today’s technologically immersed individual. The Connecticut-born former puppeteer, organist and German-based experimental dancer arguably inspired early computer artists to think inside the box. Nikolais’ box was the proscenium space and since it was a square, like the computers of yore, there is much to be said about how he foreshadowed, or recommended, ideas to the next generation of techies.

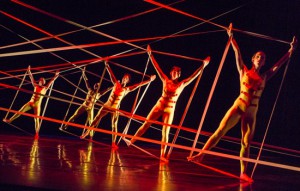

Alwin Nikolais’ Tensile Involvement: ( L to R) Aaron Wood, Bashaun Williams, Juan Carlos Claudio, Lehua Estrada, and Mary Lynn Graves. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu

Take for example Nikolais’ masterwork Tensile Involvement (1955). A pre-digital vision is created, thanks to the ten admirable dancers of the Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company—who performed all four works on the program, are dedicated to keeping his choreography alive and are guided by Alberto Del Saz, director of the Nikolais/Louis Foundation. The dancers transformed the stage into a cat’s cradle by running with an enormously long, stretchy dayglow material, which they never allowed to become slack. Look at your computer’s interface when it is on sleep mode for a modern-day example of this effect. Indeed, before the invention of laser beams, light shows and computer-generated images, Nikolais figured out how to rig a lighting plot and and employ unconventional material to generate that which hadn’t yet been discovered by engineers. Instead of clicking and coding, his dancers designed the space with their bodies, and props, to produce a vortex of intersecting lines. Nikolais’ futuristic artwork is at its most dazzling when the dancers frame themselves inside their own sets designs (or interfaces). At this moment, the decor and the dancer merged, and the audience clapped heartily. In the Renaissance, Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man expressed how the proportions of the body are the building blocks for architecture. In Nikolais’ Tensile Involvement, his dancers’ bodies express how we are comprised of particles, beams of light and energy.

The program opened with Crucible (1985), a work in which the dancers appeared and disappeared behind a large mirror. Now this may sound simple, perhaps even childish, but as the work progressed it became visually spectacular. The set resembles a big café bar. Instead of the bar’s surface being zinc, it is a black mirror and it is tilted upwards, so that when the dancers emerge from behind it, we see them and their inverted image. But unlike Narcissus, who never left the pool of water which reflected his gorgeous face, the Ririe-Woodbury dancers do everything but stare at their doppelgängers. With the mirrored set and special lighting effects, the dancers sculpt their limbs to become frogs zebras then frogs, Siamese twins then DNA double helixes. Crucible is just what the dictionary says it means: a place or situation in which different elements interact to produce something new.

Gallery (1978), the last work on the program, tendered the most sinister visions of the evening. At the finale of the eight-section work, bits of the dancers’ day-glow masks are shot off by an an invisible shooter. Like an ominous shadow that grows bigger and bigger, the work grew less child friendly and more interesting. First there were pink-green pinwheels, later hot-pink clowns violently flapping and finally a group, who stays standing despite being shot at. Gallery reads like a house of horrors and delights. This can also be said of technological innovation and Nikolais’ dances. Both continue to be glowingly relevant.