By: Frank Cadenhead

The Austrian newspaper, Der Kurier, let drop a great deal of information about what to expect in the future for the Bayreuth Festival. The new Ring in 2020, to the surprise of many, will not be conducted by the new Music Director of the festival, Christian Thielemann, but rather the Boston Symphony’s Andris Nelsons with American soprano Christine Goerke chalked in to sing Brunnhilde. She will be singing the complete Ring when the Robert Lepage production returns to the state at the Metropolitan Opera, it has been announced. Hints are that Dimitri Tcherniakov will be creating the new Bayreuth production.

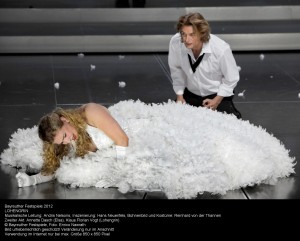

The 2016 Parsifal will also feature Andris Nelsons and will be staged by Uwe Eric Laufenberg with Klaus Florian Vogt in the title role. The 2017 performances will star Andreas Schager. That same year, Die Meistersinger will return with a new production by Barrie Kosky with Vogt as Stolzing and Michael Volle as Sachs. The 2018 Lohengrin will be conducted by Thielemann and staged by Alvis Hermanis with Roberto Alagna in the title role and Anna Netrebko as Else. There will be a new Tannhäuser staged by Tobias Kratzer in 2019. In addition to Goerke for the Ring in 2020, Andreas Schager will be the Siegfried. With time, however, things happen and with the last minute changes in this year’s casting it is way too early to carve these names in stone.

I find the lack of surtitles in Bayreuth to be a symbol of arrogant old thinking that should change. The lack of such an amenity, now literally everywhere in the opera world, is hard to explain in rational terms. If they think all of the audience has memorized the entire dialogue of the always prolix Richard Wagner they simply have never considered the question. With new technology, seat-back additions, like at the Met, would not be expensive and the one percent who have actually memorized every word can turn them off. Frank Castorf’s very detailed Ring dramatics must have left the majority of the audience in various stage of incomprehension a good part of the time.

My impression is that formal wear is now worn by the minority toward the end of the festival run. I can’t speak about opening night but you could see jeans and sport shirts at the last Ring cycle in August. The fact that there is no air conditioning at the Festspielhaus for the August festival is an added encouragement to forget the bow tie and layers.

At the end of the Castorf ring, the larger implications for Wagner’s shrine are being examined whether the regulars like it or not. My first time there, in 1963, Bayreuth and the festival reminded me of a temple of worship and the stiff, well-aged and very formal audiences were acolytes at a ceremony. Significantly, the Wieland Wagner staging of Tannhäuser (with Grace Bumbry as the Black Venus) stirred rage among the traditionalists by abstracting the stage direction. The overt sexuality of the ballet for the Venusberg music was, for me, assuringly apt but provoked the regulars. Aside from the rather more mixed audiences – more varied ages and social levels – a half-century later the Castorf staging still had the traditionalists in a lather. But, at the end of the run, I noted little of this heat. Clearly the staging was intended to puncture some balloons. This lèse-majesté began to be understood better, as with the Chereau Ring, after some time.

The festival Ring program was quite specific about what a dangerous revolutionary Wagner was. While many are aware of his anti-Semitism and assumed he grew socially conservative, Wagner advocated radical social movements all his life. Siegfried’s “Mount Rushmore” with Marx, Lenin, Stalin and Mao was no accident and his depiction of the lust for wealth and control, here “black gold,” provided a logical background for the drama.

Something that was little discussed among this year’s festival news was a fundamental change in the structure and soul of the festival that will certainly have major long term consequences. My guess is that the change, announced a few days before the start of the festival, will have a ultimate negative impact. The appointment of Christian Thielemann as “music director” of the festival first became public when the new sign for his parking place, with his new title, was widely tweeted. Some days later a press conference gave the official declaration.

Since the beginning, the festival never has had a music director. The structure formally was to hire the conductor and director for a particular opera and wait for the results. Casting was the prerogative of the conductor. Now this is not certain and Kirill Petrenko, the new designated successor to Simon Rattle at the Berlin Philharmonic, had his tenor changed just weeks before opening night and it was likely that Thielemann had something to do with that. It resulted in an uncharacteristic public statement critical of the meddling from the notoriously media-shy conductor. I would imagine this will not be the last scandal involving Thielemann who has a long history of arch-conservative remarks and trouble with management and musicians. Clearly there would be conductors and stage directors who would not consider Bayreuth while he is “music director.” My view is that this appointment, approved by the festival’s board of directors, will likely be regretted in the future.