Note: This review marks the continuation of a series dedicated to showcasing the best student writing from the Dance History course I teach at The Juilliard School.

By Alexandra Hutt

George Balanchine is famously credited with saying that “ballet is woman.” This idea is boldly apparent in his Kammermusik No. 2, which premiered on New York City Ballet in January 1978, and more recently was performed by the company as part of their 2014 winter season.

Throughout the work, seen January 22, Balanchine demonstrates his knowledge of classical ballet, stemming from his training in Russia as a child. Yet he also takes codified ballet steps and pushes them to their limits, demanding hyper-musicality, and infusing ornate, mannerist detail into both the dancers’ gestures and footwork. Alastair Macaulay of the New York Times described Kammermusik as “classicism dotted with deliberate stylistic perversions.” It is those “stylistic perversions” that exemplify Balanchine’s advancement of ballet, and reveal a more nuanced expression of his statement, “ballet is woman”; in that woman embodies Nature—and she is a force to be reckoned with.

Balanchine creates the woman as nature comparison from the beginning of his work. When the curtain rises, the principal women (Rebecca Krohn and Abi Stafford) stand apart form a corps of eight men. When the men begin moving with flexed hands and feet, they look like little spiders. Their movement deepens the intriguing musical counterpoint, ominousness and whimsy that lies at the heart of Hindemith’s score, conducted by Andrew Sills. In the more whimsical moments of Hindemith’s Kammermusik No. 2, the same men become prancing ponies, dancing in canon with a certain earnest and feminine quality. Then, they return to their insect-likeness and weave in and out of one another, as a group of ants might, when following a particularly scrumptious set of crumbs. Is Balanchine making fun of them? At the very least, he does it to elevate the roles of the women.

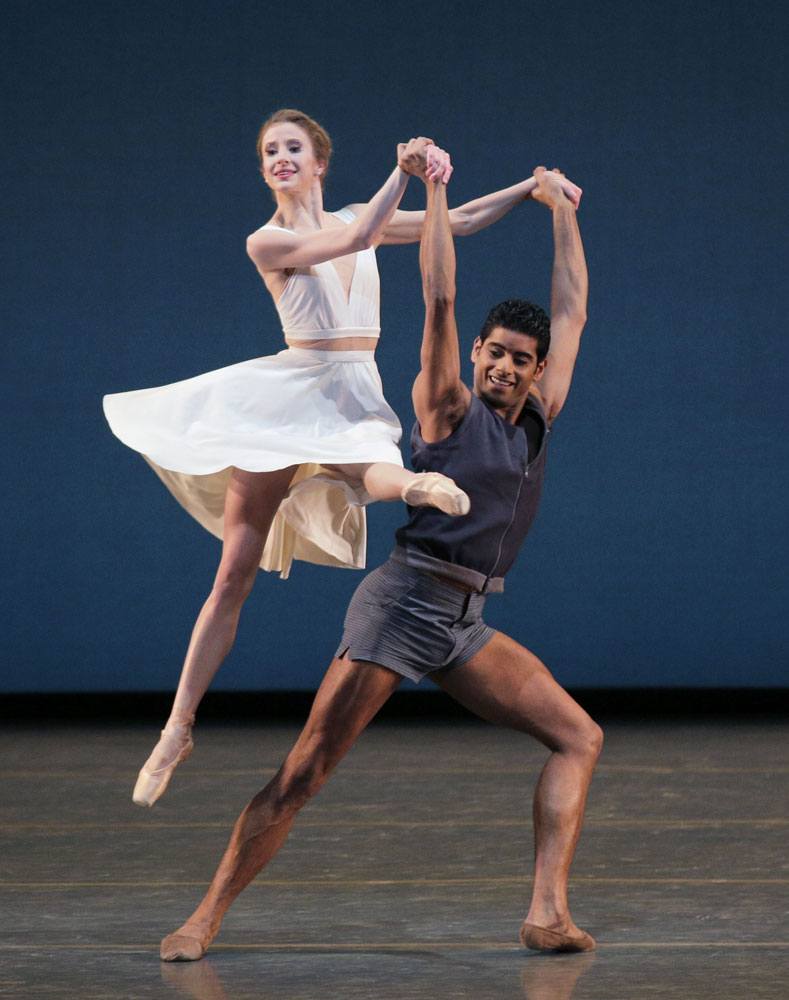

Though both the men and women in Kammermusik seem to represent four legged creatures, it becomes clear that the female creatures are of a higher taxonomic order, such as tarantulas, with their the forbiddingly long legs and extensions of them. Like their male counterparts, they skitter across the stage, but because they do so in pointe shows they devour space, while retaining an elegance that the opposite sex does not possess in this movement. Not even the choreography for the principal men (Amar Ramasar and Jared Angle) evoke the languid quality that the tarantula-women embody. The women’s sensual style gives their dancing dimension and depth. It’s a feminine kind of power. In one particular sequence, the women seem to transform into another force of nature—massive waves. With oceanic power they chase their partners off of the stage.

In Kammermusik, the women rule unapologetically. They encompass aspects of the animal kingdom that can be overlooked, such as the illusive cunning of the tigress, who will kill (or be killed) before giving up her territory. Balanchine shows the audience that when he says that ballet is woman, he isn’t referring to the tragic victims in ballet narratives of the 18th and 19th centuries. In this work, his female dancers represents a strong 20th century vision of women who aren’t afraid of their own strength and power.

**

Alexandra Hutt is originally from Denver, Colorado. She studied dance at International Ballet School, and received additional training and mentorship from Robert Sher-Machherndl of Lemon Sponge Cake Contemporary Ballet. She is thrilled to be studying at Juilliard, and looks forward to continuing her education in New York City!