Reviews

Three Days of New Music's Bold and Brightest

One of the biggest, coolest, most important new music events in New York, the three-day Long Play Festival is a 21st-century universe, the complicated elements of which perhaps can't be fully appreciated until something goes wrong. On the final day of the May 3-5 Brooklyn fest, Michael Gordon’s minimalist epic Rushes for seven bassoons was stopped after four minutes when the electronic click track—key to keeping this hectic, rhythmically repetitive piece together—broke down. During repairs, one of the players delivered a snippet from Paul Dukas’s Symphonic Poem The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, the bassoon solo made famous by Walt Disney’s 1940 animated film, Fantasia.

One of the biggest, coolest, most important new music events in New York, the three-day Long Play Festival is a 21st-century universe, the complicated elements of which perhaps can't be fully appreciated until something goes wrong. On the final day of the May 3-5 Brooklyn fest, Michael Gordon’s minimalist epic Rushes for seven bassoons was stopped after four minutes when the electronic click track—key to keeping this hectic, rhythmically repetitive piece together—broke down. During repairs, one of the players delivered a snippet from Paul Dukas’s Symphonic Poem The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, the bassoon solo made famous by Walt Disney’s 1940 animated film, Fantasia.

Great joke. Beautifully timed. Laughter was, well, minimal.

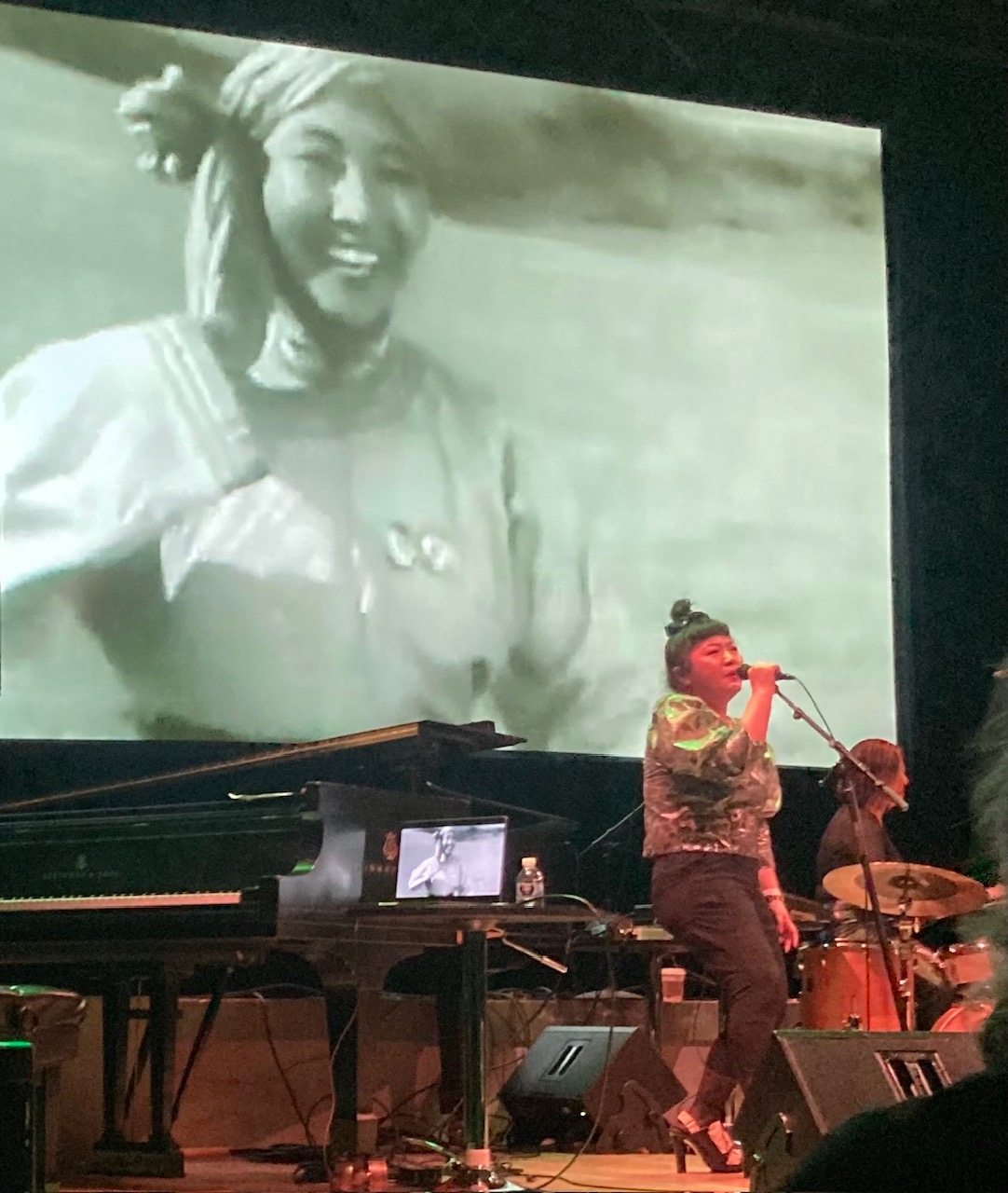

The annual alt-classical Bang on a Can event has become so much its own zip code that Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians—on the sold-out closing program at the Brooklyn Academy of Music-- occupies a slot that in traditional festivals would be reserved for Beethoven’s Ninth. Experimental niche events—Dewa Ketut Alit music that brought paper shredding sounds to the Queens College gamelan group, Chinese punk rock from the noted concerto composer Du Yun, and sound sculpting from Yosuke Fujita blowing an air gun into organ pipes—were customary among the festival’s 50-plus concerts in nine Brooklyn venues. With a schedule full of simultaneous happenings, even the most ambitious concertgoer frequently heard about missed events that were life-changing, both among new and familiar works: David Lang’s Little Match Girl Passion, for one, reportedly left the audience in tears. Gossipy chatter, for this crowd, was about whether Morton Feldman actually snored through his own meditative compositions.

Recurring themes emerged. Reich, now 87 and seemingly untouched by age, was a major and not-just-retrospective presence. Well-known works were presented in different, improved ways: His Cello Counterpoint was reincarnated by virtuoso Rebekah Heller as Grand Street Counterpoint for solo bassoon and 10 pre-recorded bassoons, a dazzling demonstration of Reich’s rhythmic invention in ways bassoons can articulate but cellos cannot. (Also significant was Heller's adaptation of Julius Eastman's The Holy Presence of Joan d'Arc, which survived only in a 1981 recording and shows the composer employing the Wagnerian concept of unending melody better than Wagner.) Music for 18 Musicians, usually percussion-dominated, was wind-instrument driven by the Bang on a Can All-Stars and more bracing because of it. Kuniko Kato performed the early Reich manifesto Drumming using sound loops and other electronic means that allowed her to play, in one form or another, all 13 parts. Watching her accomplish this also revealed how the work was built, layer by layer, adding new dimensions that wouldn't otherwise be apparent.

Recurring themes emerged. Reich, now 87 and seemingly untouched by age, was a major and not-just-retrospective presence. Well-known works were presented in different, improved ways: His Cello Counterpoint was reincarnated by virtuoso Rebekah Heller as Grand Street Counterpoint for solo bassoon and 10 pre-recorded bassoons, a dazzling demonstration of Reich’s rhythmic invention in ways bassoons can articulate but cellos cannot. (Also significant was Heller's adaptation of Julius Eastman's The Holy Presence of Joan d'Arc, which survived only in a 1981 recording and shows the composer employing the Wagnerian concept of unending melody better than Wagner.) Music for 18 Musicians, usually percussion-dominated, was wind-instrument driven by the Bang on a Can All-Stars and more bracing because of it. Kuniko Kato performed the early Reich manifesto Drumming using sound loops and other electronic means that allowed her to play, in one form or another, all 13 parts. Watching her accomplish this also revealed how the work was built, layer by layer, adding new dimensions that wouldn't otherwise be apparent.

Elsewhere in the music-making, phantom sounds often emerged out of bubbly textures, impossible for the ear to untangle much less identify which instrument was doing what. Julia Wolfe's Forbidden Love produced unexpected tings and scrapes from stringed instruments masterfully stroked and struck by So Percussion. Gordon's Rushes produced a wall of sound from individual waves of it. In John Luther Adams's Darkness and Scattered Light for five double-basses, some long-breathed countermelodies were detectable in the dark depths. Such elements might or might not be figments of a listener's imagination. In this sound world, aural mysteries can subtly fuse with what's onstage.

The festival kickoff, uncharacteristically, had rock-star charisma: Patti Smith with Soundwalk Collective. Smith read her razor-sharp, socially conscious poetry against a range of electronic sounds, some resembling fire alarms—appropriate since Smith, a sibyl-like presence at age 77, maintains the power to be alarming. Hyperactive visuals with woolly edges and other effects suggesting decay made an appropriate backdrop to her withering observations about “radiantly radioactive” climates and “soldiers with no war” and spiritual pronouncements like “God does not abandon us; we are all he knows.”

Steve Reich's Music for 18 Musicians at the Brooklyn Academy of Music as the grand finale

In Smith’s social commentary, words emerged more prominently than music. She got across her message across by aligning the accompanying elements of music and visuals skillfully, thereby lending an urgency and creating a context that the audience could easily grasp. Less successful in its messaging was the opera The Great Dictionary of Yiddish Language by Alex Weiser and Ben Kaplan, presented in a concert version by American Opera Projects. The piece is what the title says: Linguist Yudel Mark embarks on a lifelong quest, discovering thousands of Yiddish words as a matter of preserving post-Holocaust cultural identity. Certainly it is an important message, but Weiser’s restrained music is so keen to stay out of its way that a scholarly essay in the New York Review of Books would have had more impact. The score creates some heat during the more argumentative scenes and in para-normal visitations, but mostly all it does is keep the narrative afloat. Worthy intellectual pursuits notwithstanding, the Long Play Festival is about bolder artistic expression.

Above right: Du Yun as rock star commenting on traditional Asian female roles

Reich photo by Stephanie Berger

Classical music coverage on Musical America is supported in part by a grant from the Rubin Institute for Music Criticism, the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and the Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation. Musical America makes all editorial decisions.

WHO'S BLOGGING

Law and Disorder by GG Arts Law

Career Advice by Legendary Manager Edna Landau

An American in Paris by Frank Cadenhead

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO