Special Reports

Digital vs. Print: Three Committed Converts

![]()

Many soloists and chamber groups have completely abandoned paper scores for tablets and iPads

Violinist Ray Chen

Ray Chen deserves at least a footnote in the history of digital scores. He was one of the first to play from a digital music reader in a major competition. At the 2009 Queen Elisabeth Competition in Belgium, he used a laptop, with a foot pedal for page turns, to play a commissioned work for violin and piano, V…, by Claude Ledoux.

“The work was very difficult, full of complex rhythms, with impossible page turns, and most people in the competition either had to print out extra sheets of music and put it across like three stands or make a giant billboard,” Chen says. “But since page turning wasn’t a problem, instead of just playing the single line of the violin and having no clue of what the piano was doing, I used the whole score, so I could see the overall map of the piece. That really saved my butt in the competition and enabled me to focus purely on the music.” (There’s a video of the performance on the competition web site.)

Chen won the competition, and ever since the iPad came out in 2010, it has been his constant companion as he performs around the world. For most concertos, he will have the work memorized and doesn’t use the device (though he played Britten’s First Violin Concerto from it last year with the Buenos Aires Philharmonic), but for chamber music it is invaluable. “For anything that’s not a concerto—for the sonatas, for the quartets, quintets and trios that I play—I’ll have the iPad there,” he says.

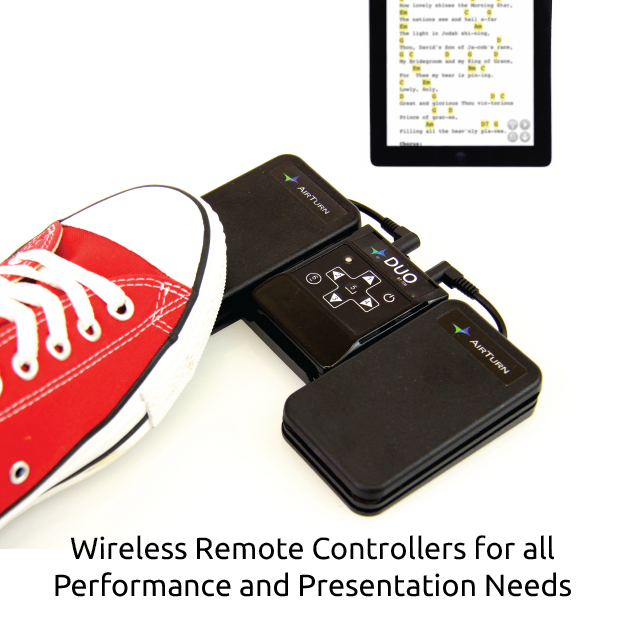

The specifics of his setup are typical of digital score users: His iPad is connected to a Bluetooth foot pedal from AirTurn, a company that makes wireless page-turners that was co-founded by Hugh Sung, a pianist and former faculty member of the Curtis Institute of Music, where Chen studied. He scans sheet music using his smartphone camera with software by TurboScan, and the app forScore allows him to make annotations to the score. (PHOTO: Chen in his winning performance at the 2009 Queen Elisabeth Competition.)

“It’s easy to use,” Chen said. “You don’t have to be tech savvy. I basically turn it on.

The Borromeo String Quartet

The Borromeo String Quartet, which began using digital readers in 2007, was an early adopter of the technology for strictly musical reasons. First violinist Nicholas Kitchen wanted to have the group read music from the full, four-part score rather than from individual parts, as is customary in most ensembles. Playing, say, a Beethoven quartet from the full score would take more than 100 page turns, many in very inconvenient places. With a foot pedal, however, the turns are virtually seamless.

“Once you get the hang of turning pages with your foot, there is no barrier to having a score with as many pages as you wish,” says Kitchen, who reads his music off a MacBook Pro that has a 17-inch screen, larger than an iPad. “And reading from the complete score all the time has been a profound, wonderful change.”

Cellist Matt Haimovitz

Matt Haimovitz plays off his iPad, through which he stores more than 750 scores in the cloud, accessible at the flick of a finger. “I can travel anywhere and I have all those scores with me,” Haimovitz says. “When I change up a program, or decide on the spot to play an encore, it’s all right there.”

He annotates his scores using forScore and a stylus. “A setting allows you to mark it up in different colors, which is easy on the eye and the brain,” he said. “I can quickly go in there and change something. If I’m playing a Brahms piano trio with one violinist and pianist, and then two weeks later I play the same piece with different people, I can save a version of the score for each group, with different markings. I don’t have to see all the erasures and markings that I would have had to make on paper.”

In four years of playing from an iPad, Haimovitz has been remarkably free of glitches. “I’ve had it crash only once in concert, and that was partly my fault because I upgraded the forScore software without upgrading the operating system, so it just wasn’t happy,” he said. “It was in the middle of a Brahms piano quartet at the Beaux Arts Museum in Montreal. Fortunately I remembered the rest of the piece and was able to go on, but I was like a deer in the headlights.”

Haimovitz commissioned six composers—Philip Glass, Du Yun, Vijay Iyer, Roberto Sierra, Mohammed Fairouz, and Luna Pearl Woolf (his wife)—to write overtures for the J.S. Bach Cello Suites, using the manuscript copy by Anna Magdalena, Bach’s second wife. “I got the overtures digitally,” he said before they were to be premiered this fall. “The composers sent me PDFs that went directly into my iPad library, and we made any revisions digitally. In the past we would have been mailing sheet music back and forth. I don’t know how we did it.”

John Fleming writes for Classical Voice North America, Opera News, and other publications. For 22 years, he covered the Florida music scene as performing arts critic of the Tampa Bay Times.

WHO'S BLOGGING

Law and Disorder by GG Arts Law

Career Advice by Legendary Manager Edna Landau

An American in Paris by Frank Cadenhead

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO