100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (246)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (246)

June 8, 1918

Page 25

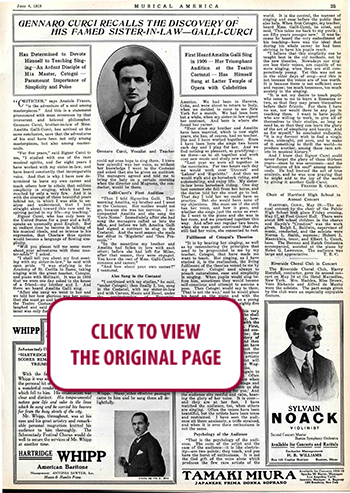

GENNARO CURCI RECALLS THE DISCOVERY OF HIS FAMED SISTER-IN-LAW—GALLI-CURCI

Has Determined to Devote Himself to Teaching Singing—An Ardent Disciple of His Master, Cotogni—Paramount Importance of Simplicity and Poise—First Heard Amelita Galli Sing in 1909—Her Triumphant Audition at the Teatro Costanzi—Has Himself Sung at Latter Temple of Opera with Celebrities

“CRITICISM,” says Anatole France, “is the adventure of a soul among masterpieces.” And this is a statement pronounced with most reverence by that irreverent and beloved philosopher. Gennaro Curci, brother-in-law of Mme. Amelita Galli-Curci, has arrived at the same conclusion, save that the adventures of his soul have been not only among masterpieces, but also among master souls.

“For five years,” said Signor Curci to me, “I studied with one· of the rare musical spirits, and for eight years I have worked with my sister-in-law, and have heard constantly that incomparable voice. And that is why I have now determined to leave my own career and teach others how to attain that sublime simplicity in singing, which has been reached by only a very few. And it is with the courage of these beautiful years behind me, in which I was able to analyze and understand, that I look straight ahead toward this new. and inspiring period in my life--my teaching.” Signor Curci, who has only been in the United States for a year and a half, speaks an unusually good English. But so radiant does he become in talking of his musical ideals, and so intense is his expression, that Choctaw thus spoken would become a language of flowing simplicity.

“Will you please tell me some more about~ your adventures with these master- souls?” I asked.

“I shall tell you about my· first meeting with my sister-in-law,” he said with open pride. “I was studying in the Academy of St. Cecilia in Rome, taking singing with the great teacher, Cotogni, and piano with Molinari. It was in 1909 that we were one day asked to the house of a friend-my brother and I. And there we heard Amelita Galli sing.

“After she sang we went to her and we told her how glorious was her voice; that she must go and have an audition at the Teatro Costanzi. Signorina Galli laughed and said that the Teatro Costanzi was only for great singers and she could not even hope to sing there. I knew how splendid was her voice, so without her knowledge I went to the Costanzi and asked that she be given an audition. The managers agreed and told me to bring the lady on a certain morning when the director and Mugnone, the conductor, would be there.

Galli-Curci’s First Audition

“Then I told Signorina Galli. That morning Amelita, my brother and I went to the Costanzi. Her mother would not go, because she was too nervous. I accompanied Amelita and she sang the ‘Caro Nome.’ Immediately after she had sung the managers called us into the office, and before we left Amelita Galli had signed a contract to sing in the Costanzi. And the next season she made her debut in ‘Rigoletto’ and ‘Don Procopio.’”

“In the meantime my brother and Amelita had fallen in love with each other; before she had left for Milan, after that season, they were engaged. You know the rest of Mme. Galli-Curci’s romance and career.”

“And how about your own career?” I ventured.

Also Sang in the Costanzi

“I continued with my studies,” he said, “under Cotogni; then finally I, too, sang in the Costanzi, with my sister-in-law and with Caruso, Muzio and Bonci, under the conductorship of Toscanini, Mugnone, Mascagni and Guarnieri. I sang in the first performance of ‘Isabeau.’ After that we toured all through Europe, and then in South and Central America. We had been in Havana, Cuba, and were about to return to Italy, when we decided to come to see New York for a month. We had been here but a while, when my sister-in-law signed her contract. And here is where she found her career.

“Ever since my brother and Amelita have been married, which is now eight years, she has, of course, had no teacher. She and I have worked together. Since I have been here she sings two hours each day and I play for her. And we find nothing so pleasant, so gratifying—we three—as to sit together and work over new music and study new works.

“Last year we were all together in the mountains. For two hours each day we would work over ‘Dinorah’ and ‘Lakme’ and ‘Rigoletto.’ And then we would walk and go horseback riding, and automobiling, and enjoy life. My sister-in- law loves horseback riding. One day last summer she fell from her horse, and the doctor told her she must go to bed. That day I told her we could have no practice. But she would have none of ·my objections. She must see if she still has her voice, and how it goes, and whether she sings just the same as ever. So I went to the piano and she was in her room, and we practised together this way. And after our regular two hours, when she was quite convinced that she still had her voice, she consented to rest.

Fulfilment of Cotogni’s Theories

“It is by hearing her singing, as well as by remembering the principles that used to be propounded to me by my teacher, Cotogni, that have made me want to teach. Her singing, as I have studied it, is the realization, the living fulfilment of the theories voiced to me by my master. Cotogni used always to preach naturalness, ease and simplicity in singing. When pupils would sing before him, sometimes they would become self-conscious and attempt to assume a pose. Then Cotogni would say to them, ‘That is not the way,’ and he would place his hand on the piano and with the greatest ease sing as purely as a young man, though he was then eighty-five years of age.

“It is this same simplicity, this very ease that I wish to teach those who shall be my pupils. It is a simplicity, however, that can be acquired only with the utmost and all-consuming work. First, it requires absolute knowledge and control of the mechanical apparatus; the ability to have continuous mastery of the vocal organs, of course. And then the person must be an artist, must have the soul of a musician, as must the teacher. So that the voice, however fine it may be, will be used with artistic discrimination; so that the artist will not seem to be singing Verdi, or Wagner, or Bach as if they were alike.

“Above all, however, I wish again to emphasize simplicity in singing. Often I have sat watching the audience when Amelita sings. She is on the stage and she seems to be saying to them as she sings, ‘I love to be singing for you.’ And the audience sits restful and calm, hearing the glory of her voice. It is over—and they are at her feet. I have watched the audience, too, when others are singing. Often the voices have been beautiful, but the artists have been tense and restrained. I have seen the audience sit there anxiously, a trifle strained, and when it is over their enthusiasm is not the same.

Psychology of the Audience

“That is the psychology of the audience. The calm of the artist and the ease of the audience—it is like electricity—are two points; they touch, and you have the burst of enthusiasm. It is not the God gift of the voice alone which produces the few rare artists of the world. It is the control, the manner of singing and ease before the public that also help. When first Cotogni, my teacher, heard Mme. Galli-Curci, he cried, and said, ‘This takes me back to my youth; I am fifty years younger now.’ It was because he heard the very embodiment of his teaching—here was the ideal that during his whole career he had been striving to have his pupils reach.

“I believe that this simplicity can be taught best in the old methods, not by the new theories. Nowadays our singers lose their voices, are capable of no more singing, when they are still comparatively young. Yet this was not so in the older days of song—and this is not because the voices are of less worth. It is because there is not sufficient ease and repose; too much tenseness, too much anxiety in the singing. “It is not my desire to teach pupils who come to me to learn a Romanza or two, so that they may preen themselves before their friends. For them I have no use, nor would there be any joy in teaching them. I want to have pupils who are willing to work, to give all of themselves to their studies, as long as need be, so that they can learn the glory of the art of simplicity and beauty. And as for myself,” he concluded radiantly, “it· is my fervent wish to find a virgin voice, untaught, yet pure, and to make of it something to thrill the world—to produce another, among those rare artists in musical history.”

And I knew that Signor Curci could never forget the glory of those thirteen years—since he was seventeen—and the “adventures of his soul” among master-souls. He had learned the art of true analysis, and he was now praying that he might add to the joy of the world by giving it another Galli-Curci. —FRANCIS R. GRANT.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO