100 YEARS AGO...IN MUSICAL AMERICA (40)

100 YEARS AGO...IN MUSICAL AMERICA (40)

February 28, 1914

Page 1

ELABORATE SETTING FOR CHARPENTIER’S NEW OPERA ‘JULIEN’

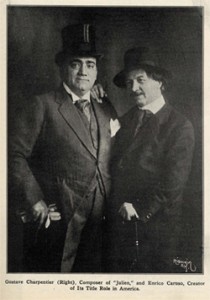

With Caruso and Farrar in Cast, Latest Product of French School Has a Spectacular Mounting at First New York Production—Symbolic of Futility of Idealism—Not Really a Sequel to “Louise”—Work Well Performed by Metropolitan Company

By HERBERT F. PEYSER

WHAT may or may not have been intended as a concession to those who for the past few seasons have lifted up their voices in more or less unavailing clamor for French opera was brought about with the first American performance of Gustave Charpentier’s “Julien” at the Metropolitan Opera House on Thursday evening.

That it will in appreciable measure satisfy these widespread demands or, on the other hand, serve as a forcible refutation of their legitimacy is open to doubt. True, it is impossible at the present writing to record the verdict of the first night audience owing to the lateness in the week of the premiere. But certain valid conclusions as to the artistic qualities of the work can be derived from two hearings of it at full dress rehearsals and others under less normal circumstances.

The ensuing comments, therefore, are made with reference to the private performances of the opera given last Sunday and last Tuesday mornings. “Julien” is an elaborate spectacle and has the advantage of Caruso and Geraldine Farrar in the leading rôles. These facts will probably be the greatest incentives it can offer to popular consideration and acceptance. As dramatic and musical bait it is distinctly less tempting.

The circumstances prompting the adoption of “Julien” for Metropolitan usage have never been set forth quite definitely enough to satisfy all speculation which has arisen in connection with the matter. Charpentier’s opera, much talked of and impatiently awaited abroad, failed signally when exhibited at the Opéra Comique last June. Paris critics, generally prone to enthusiastic effusions on very slight provocation, cooled perceptibly on contact with it. Some conjectured that the unpopularity of the composer with many Paris musicians might have something to do with the widely prevalent attitude, some blamed the quality of the interpreters, others the nature of the mise-en-scène. Many frankly denounced the thing as tiresome and a few found it enjoyable. Nevertheless the subsequent career of “Julien” was not brilliant and no other foreign opera house made efforts to acquire it. The present performance is therefore its first outside of Paris.

Caruso Likes the Rôle

At all events the tepid reception at the Opéra Comique did not disconcert the powers that rule at the Metropolitan. It was there maintained that “Julien” did not conclusively fail, that with a mounting more sumptuous than had there been provided for it and enacted by a more competent cast it might look for hospitable treatment in New York. Furthermore Mr. Caruso was much fascinated by the title rôle; Julien occupies the stage almost incessantly and the adorers of the great tenor worship quantity. The .lessons of “Germania” were forgotten and “Julien” became an assured promise. Charpentier was to have hallowed the première by his presence in the flesh. But the midinettes of Montmartre wished to present him with the Academician’s sword and he also caught cold. Hence he remained at home.

Mr. Gatti has fulfilled his promise relative to the sumptuous scenery (it was executed by Paul Paquereau) and to the excellence of the interpreters provided. Mr. Caruso, Miss Farrar and the splendid chorus carry the burden of the work. Rôles of subsidiary account are sustained by Messrs. Gilly, Reiss, Murphy, Bada and Mmes. Duchène, Maubourg, Mattfeld, Braslau, Curtis and Cox.

The production bespeaks care and obvious ‘devotion. It is executed on a large scale of notable brilliancy, with nice adjustment of all constituent factors. “Julien” leans heavily for its effects on scenic sumptuousness and evenness of choral’ work. Both of these ends have been achieved at the Metropolitan. The chorus—as much a distinct personality in the drama as it is in “Boris”—sings its very considerable share superbly, particularly in the suavely melodious ensembles of the first act and the riotous episodes of the Montmartre revels. On the whole there is much beauty in the successive settings in spite of an occasional excessive garishness or crudity of coloring. The ascent to the Temple of Beauty and the interior of the Temple are picturesque, the Slavic landscape, peacefu1 and charming, the storm-swept port in Brittany striking. It is a pity, though, that moving cloud effects could not have been obtained in the latter—especially as the Metropolitan possesses such an effective moving “skyscape.”

Last Act the Scenic Climax

But the scenic climax of “Julien” is the last act when out of a mysterious darkness the brilliantly illumined Place Blanche bursts suddenly into view with its electrically illumined Moulin Rouge, its circus-like “side shows,” its reveling throng. Vivid and bustling with life and gayety it comes as a welcome contrast to the depression that has preceded. If “Julien” succeeds it will be due in large measure to the fascinations of this scene.

There are but three rôles of anything like substantial account in the opera—those of Julien, Louise in her various reincarnations and the High Priest in his. The shorter parts—including those of the cynical Acolyte and Bellringer well done by Messrs. Reiss and Ananian—are adequately handled.

Mr. Caruso bears the brunt of the solo work. But whether the rôle will prove among his most popular is open to question. He sings the music well but, though he throws himself into the part with much earnestness and fervor, his success in expressing its subtler phases is not altogether eminent. Nor was it to be expected that it would be. The evident sincerity of his efforts, however, is certainly deserving of recognition. But why does Mr. Caruso represent Julien as a blond when he has always been dark-haired in “Louise,” will doubtless be asked by many. Charpentier is himself to blame for the incongruity for in the opening scene Louise is made to refer to Julien as “le blond poète que j’adore.”

Mr. Caruso bears the brunt of the solo work. But whether the rôle will prove among his most popular is open to question. He sings the music well but, though he throws himself into the part with much earnestness and fervor, his success in expressing its subtler phases is not altogether eminent. Nor was it to be expected that it would be. The evident sincerity of his efforts, however, is certainly deserving of recognition. But why does Mr. Caruso represent Julien as a blond when he has always been dark-haired in “Louise,” will doubtless be asked by many. Charpentier is himself to blame for the incongruity for in the opening scene Louise is made to refer to Julien as “le blond poète que j’adore.”Mr. Gilly sings his parts of the High Priest, the Peasant and the Magician at the fair excellently, impersonating the first with especial dignity and breadth. Miss Farrar’s Louise is beautiful to behold in the Temple of Beauty, and as the Peasant Girl she is simple and touching. But the climax of her achievement is the Street Girl of Montmartre when, attired in a slit skirt through which flares scarlet hosiery she presents a vivid portrait of the type with astonishing fidelity. The nasal twang of her speech, the coarse laughter, her gait, the lascivious movements are striking in verisimilitude. It is a sketch of astonishing effectiveness in every detail and not overdrawn to the point of inartistic vulgarity.

Mr. Polacco conducted with animation and great spirit and also with an exquisite sense of nuance, bringing out every telling detail that was to be revealed. It was an achievement that could not have been bettered. The orchestra gave of its best.

Not Really a Sequel to “Louise”

“Julien” has been widely given out as the sequel to the popular “Louise.” Yet the two operas have little more in common than the names of the two principal personages, the episodic quotation in the score of two or three themes from the earlier work, and a scene of revelry on Montmartre. Charpentier has turned to account his seldom heard symphonic drama “La Vie du Poète”—written for chorus, soli and orchestra and composed during his sojourn in Italy following upon his capture of the Prix de Rome—and has incorporated much of it in his latest opera. “Julien,” indeed, bears upon the title page of its score the optional title “La Vie du Poète.” But whereas “Louise” was a plain, unvarnished tale steeped in an atmosphere of bald literalness and bare realism, “Julien” is a pretentious composite of allegory, more or less poetic symbolism, fantasy, grotesquerie, realism and so on for quantity. “Louise” was very evidently the preachment of a doctrine, though opinions differed as to which one of two ethical considerations it purported to enforce. In “Julien” he vents a philosophy of out-and-out pessimism and omits no opportunity to drive home his view. A brief outline of the libretto will serve to make this point clear.

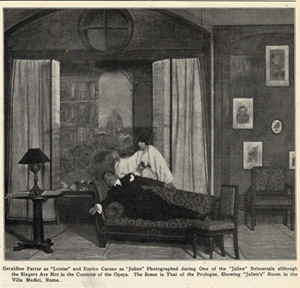

A prologue in the Villa Medici in Rome discloses Julien and his beloved Louise. It is evening, Louise is sleeping. Julien upon entering apostrophizes his “great work” affectionately and looks lovingly upon the papers that strew his working table. Throwing himself on a sofa, he glances through one of his poems and presently, murmuring happy and ambitious things, falls asleep. Louise awakes and tenderly observes the sleeper. She is dear to him but he forgets her occasionally in his ardor for his poetic creations and when he undertakes “saint-like to preach universal love to the multitude.”

A prologue in the Villa Medici in Rome discloses Julien and his beloved Louise. It is evening, Louise is sleeping. Julien upon entering apostrophizes his “great work” affectionately and looks lovingly upon the papers that strew his working table. Throwing himself on a sofa, he glances through one of his poems and presently, murmuring happy and ambitious things, falls asleep. Louise awakes and tenderly observes the sleeper. She is dear to him but he forgets her occasionally in his ardor for his poetic creations and when he undertakes “saint-like to preach universal love to the multitude.”The scene dissolves into a view of the “Sacred Mountain” on the summit of which is perched the Temple of Beauty. Official word has gone forth from the Metropolitan to the effect that this and the subsequent scenes of the opera constitute the dream of the sleeping Julien. Yet there is nothing in the libretto or score to indicate this fact, nor does any epilogue reveal the awakening of the poet. As the opera is purely symbolical and fantastic there seems no valid reason for regarding it apologetically as a vision, though it concern itself with dreams in a figurative sense. Possibly, there be those who deem it wisest thus to sugar-coat the allegorical pill that the dear public may not feel moved to accept such matters in too deep a seriousness of spirit.

Dream Maidens, Dream Pilgrims, Servants of Beauty, Chimeras, and other personifications of abstractions, accompany Julien and Louise in their ascent toward the Temple. From an abyss are heard the wails of the Fallen Poets who met defeat in their pursuit of ideals. Julien is moved to pity and vows to succor them. He is accepted as a devout follower of Beauty by the High Priest, who warns him, however, of the agonies awaiting all who would benefit and uplift humanity. But Julien is resolute and devoutly prostrates himself at the feet of Beauty, who suddenly reveals herself in the shape of Louise. Meanwhile an Acolyte and a Bellringer—typical of the cynic and materialist—utter scoffing remarks.

In the second act Julien, rejected by those he sought to aid, is seen wretched and consumed by doubt as to the real worth of his mission, at the door of a cottage in a Slavic country. Woodcutters, harvesters and other rural laborers chant lugubriously of the hopelessness of toil. A sympathetic peasant’s daughter pities him and begs him to remain. She offers to console him for his Louise, who has died. The stern but kindly peasant, who seems to resemble the High Priest in the Temple of Beauty bids him enter or leave. He chooses the latter alternative. Wandering to the coast of Brittany he is exhorted by an aged woman in the third act to religious faith. But as he hesitates the voices of the Fallen Poets are heard voicing maledictions on their fate and Julien casts aside the aged woman—a reincarnation of Louise, this time the embodiment of faith—and betakes himself to Montmartre, where he is seen in the fourth act, amid the revels of a sordid throng, haranguing the mob in the praise of physical indulgence. AGrisette has fascinated him. The crowd destroys the “Theater of the Ideal” which adorned a part of the square. Julien, left alone with the Grisette, sees, as in a momentary vision, the hall of the Temple of Beauty and overcome by the contrast of his present and former state, collapses at the feet of the street walker who laughs stupidly as three distant wails denote the annihilation of his once-cherished ideals.

“Louise” was said to have been to a certain extent autobiographic. Perhaps in a more subtle sense “Julien” is the same. The present, however, is no place for a protracted disquisition upon Charpentier’s distressing outlook upon life—a point of view diametrically opposite to that put forth by Wagner. It is, in truth, as essentially French as Wagner’s is German. For the ebullient Gallic sparkle and levity is superficial and rests often upon a somber spiritual basis of pessimism. “Julien,” however, is not altogether convincing in its deductions. Julien, despite his protestations, is not an indomitable will. He is denoted not as a potent spirit in conflict with cynicism, malice and materialism, but as one in whom temporary rejection has engendered doubt as to the validity of his own ideals. Such a conception is never utterly persuasive and Charpentier’s premises are not sufficiently well grounded to allow his argument to strike with the force of terrible finality which he doubtless intends them to carry. Julien is fundamentally weak and little is to be gained from the contemplation of the tragedy of such weakness. Its exposition savors of futility.

But it is scarcely probable that the average operagoers will be moved to philosophical speculations on observing this elaborate phantasmagoria which the composer has so sedulously and ostentatiously supplied with metaphysical labels—least of all in the glittering spectacle of the first and last acts. Here is shown pageantry of one sort or another in abundance. The spirit of Meyerbeer is still harbored in the soul of French composers and Charpentier nourishes himself with it very liberally—recall the third act of “Louise,” for example. In “Julien” he has far outstripped his former self in this respect.

The divers characters apart from Julien, being either abstract types or the embodiments of states of consciousness, do not call for consideration. However, the chorus assumes a condition of prime importance, its attitude reflecting the inner mood of the poet.

As in his earlier opera the composer has also assumed the function of librettist. He has the literary gift and much of “Julien” is written with elegance of style and expression and true poetic fancy. The concluding act brings with it not a little of the characteristic argot of Montmartre. There is atmosphere and vividness in this episode. Why Charpentier should have taken the desolate Julien to a Slavic country in the second act is not clear. Possibly he felt impelled to follow in the footsteps of Berlioz who led his Faust to Hungary in order that he might, with some show of reason, introduce into his opera the stirring “Rakoczy March.” Charpentier, however, makes no effort to vivify his music with a touch or two of Slavic color, by the introduction of some characteristic Slavic rhythm or melodic turn.

Musically “Julien” falls very much below “Louise,” save, perhaps, in the matter of instrumentation in which it discloses greater smoothness and more equable balance in addition to many charms of color. But it quite lacks the sincerity, the cohesiveness and the directness of that score. It is ponderous, inflated and for the greater part dull; often platitudinous and never distinguished. Charpentier has neither fineness of imagination, originality of invention nor the depth of expression appropriately to translate his poetic conception. His quality of musical thought is of a distinctly ordinary fiber. By virtue of certain trimmings of ultra-modern harmony which he has at his disposal he succeeds at times in giving a momentary semblance of dignity to ideas intrinsically commonplace. But when he occasionally lays aside the harmonic whitewash the consequences tend to become deplorable.

“Julien’s” lack of variety and contrast are factors most inimical to its popular well-being. For three acts the emotional atmosphere is unrelievedly somber. This, of course, would be no irremediable detriment did the quality of the musical fabric atone for the sameness of mood and sluggishness of movement. It is truly surprising that one who displayed so excellent a sense of the theater as Charpentier did in “Louise” should have erred so conspicuously in the present case. To be sure the much-needed relief is to be found in the Montmartre scene, but this comes dangerously late in the opera to retrieve the monotony of what has preceded. The vulgar, blatant tunes of the revelers—emphasized and vociferated by a stage brass band—are, however, highly appropriate and in keeping with the character of this bustling and—by contrast—entertaining episode. On the other hand the collapse of Julien at the close is astonishingly ineffective from the musical standpoint.

Charpentier set himself a broader task than he—or, indeed, most French composers—could encompass in endeavoring to express musically the philosophical concept which he has here advanced. Only once does he draw a truly suggestive tonal mood picture—namely, in the opening portion of the second act, where the prevalent sense of spiritual lassitude, dejection and the inutility of effort is mirrored in the music. The tristful refrains of the laborers enforce the emotional keynote of the situation as do the street cries in the second act of “Louise.”

Apart from this the composer can scarcely be said to evince true penetration, to lay bare in tone the soul of Julien, extravagantly as he has pretended to do so. He is not infrequently sentimental in the manner of Massenet at his least inspired state. But he is neither succinct, subtle, trenchant or intense. He talks at length but says little. In his harmonic methods Charpentier has not advanced beyond that complaisant middle ground of modernity which he maintained in “Louise.” His eclecticism is rather less happily disguised than it was in that opera. He still draws to some extent on Wagner—the pretty chorus of Chimeras in the first act harks back the Klingsor’s Flower Maidens. There is a quantity of Massenet and, of course, Debussy lends his aid for harmonic flavoring. As Charpentier used representative themes in “Louise” so has he done here. Often reiterated they are seldom significantly or subtly modified. The three or four transferred from “Louise” are infrequently heard and their employment is episodic.

NEW CITIES JOIN IN NATIONAL MOVEMENT

Buffalo and Cleveland Audiences Endorse Campaign for America’s Musical Independence—Addresses by John C. Freund in These Cities Applauded by Representative Audiences

Buffalo and Cleveland Audiences Endorse Campaign for America’s Musical Independence—Addresses by John C. Freund in These Cities Applauded by Representative Audiences

ADDED evidence that the musical communities of the United States are eager to join in the national movement for the declaration of America’s musical independence was afforded last week by representative gatherings of musical persons in Buffalo and Cleveland. The campaign which MUSICAL AMERICA has begun and which has been prosecuted on the public platform by John C. Freund, its editor, has now received support and hearty endorsement in Atlanta, Nashville, Baltimore, Detroit, New York, Washington, Columbus, Cincinnati, Buffalo and Cleveland.

Mr. Freund in Buffalo

BUFFALO, Feb. 19.—John C. the able editor-in-chief of MUSICAL AMERICA, gave a lecture here February 18, his subject being “The Musical Independence of the United States.” An audience representative of the best in music and letters in the city listened to the speaker, who was introduced by Judge George A. Lewis, with the closest attention, and there can be no question as regards the deep impression he made.

Musical Buffalo is awake to the fact that America, or at least that part that the United States represents, is an artistic factor to be reckoned with. It needed just such a polished and forceful speaker as Mr. Freund, with his enormous store of musical knowledge allied to the statistics he presented, to make people stop and think, and there is some deep and serious thinking being done here just now which is sure to bear fruit.

He made it quite plain that the attitude of many Americans in regard to the beautiful and artistic at home has been snobbish and in some instances criminally careless, though on this side of his subject he touched lightly. He made it plain that our young men and women can get sound musical educations at home and generally in their home cities and he cited numerous music conservatories where the tuition is of the best. He also spoke in terms of warm praise of professors of music in the different music branches that live in America, whether or not of foreign extraction, ranking them with the best in the world.

Mr. Freund interspersed his lecture with some delightful personal reminiscences which extend over an active career of forty years and all of these reminiscences had direct bearing on the subject in hand. He frankly acknowledges our debt to musical Europe, but feels we have paid it by absorbing the best it can give us. It was evident that Mr. Freund’s attitude is not against Europe, but that it is solely for America and American musical independence. His address will long be remembered as a master effort and he has the satisfaction of ‘knowing that musical Buffalo has fallen into line and that he can depend on the sincere and hearty support among musicians here, of his propaganda.

At the close of the lecture, after prolonged and hearty applause, Angelo M. Read, a prominent musician in the audience, arose and made the following resolution: “Mr. Chairman, be it , resolved that the musicians and music-lovers of Buffalo extend to Mr. Freund their thanks for his address on American independence in music, and, furthermore, that we, as a body, indorse the stand that Mr. Freund is taking in sustaining American educational institutions, and especially American independence in music.”

This resolution was unanimously indorsed by all present.

Among musicians and others noted in the audience were Mr. and Mrs. Angelo M. Read, Mary M. Howard, Amy Graham, Mrs. George A. Lewis, Ruth Lewis Ashley, Mrs. Jane Showerman McLeod, Mme. Frances Helen Humphrey, Lillian Hawley, Florence Ralph, Katherine Kronenberg, Marjorie Shannon, Carrie Jennings, Mrs. John Adsit, Mrs. Henry Dunman, Mr. and Mrs. W. H. Boughton, Mme. Blaauw, Dr. Edward Durney, Andrew Langdon, Tracey Balcom, ,Reed C. Schermerhorn, Leon Trick, Harry Cumpson, W. S. Jarrett, Marian De Forest, Rev. Father Bonzin, Dr. J. J. Mooney, Mrs. Herbert Chester, Dr. and Mrs. Henry Boswell, Mary B. Swan, Max Goldberg, Mr. and Mrs. Walter Hawke, Lavinia Hawley, Clara Diehl and Mrs. Mai Davis Smith through whose efforts Mr. Freund was induced to come on here and give his remarkably interesting and instructive lecture. —F. H. H.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO