100 YEARS AGO ... IN MUSICAL AMERICA (36)

100 YEARS AGO ... IN MUSICAL AMERICA (36)

February 7, 1914

Page 9

BELIEVES “TRISTAN” CAN BE SUNG BETTER IN ITALIAN THAN GERMAN

Ferrari-Fontana Declares Wagner Himself Would Have Rejoiced if He Could Have Heard His Music Free of Teutonic Gutturals —Greatest Future Hope for Italian Opera in Men Like Montemezzi, Declares the Tenor of “L’Amore dei Tre Re”—Home Life of a Happily Married “Tristan” and “Isolde”—The Silver Spoon of Adrienne Ferrari-Fontana

By OLIN DOWNES

Bureau of Musical America, No. 120 Boylston Street, Boston, January 31, 1914.

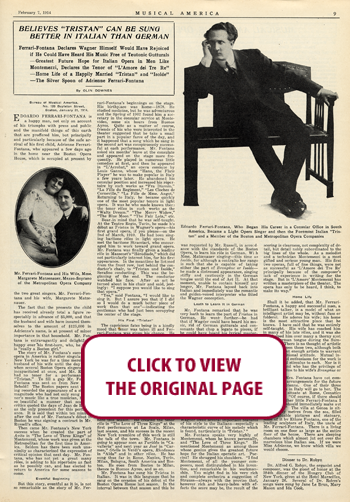

EDOARDO FERRARI-FONTANA is a happy man, not only on account of his triumphs with press and public and the manifold things of this earth that are proffered him, but principally and particularly because of the safe arrival of his first child; Adrienne Ferrari-Fontana, who appeared a few days ago in the home near the Boston Opera House, which is occupied at present by the two great singers, Mr. Ferrari-Fontana and his wife, Margarete Matzenauer.

The fact that the presents the child has received already total a figure respectably in advance of $5,000, and that the husband and wife have insured themselves to the amount of $125,000 in Adrienne’s name, is at present of minor importance in that household. Mr. Fontana is extravagantly and delightfully happy over his first-born, who, he says, is “really a Boston girl.”

The story of Mr. Fontana’s success in opera in America is rather singular. In New York he was for a time merely the husband of his wife until the day came when several Boston Opera singers were incapacitated at once, and Mr. Russell had no tenor for a performance of “Tristan.” To fill a gap Mr. Ferrari-Fontana was sent on from New York. Behold! The Boston papers next morning recorded the appearance of a star of magnitude who had not only sung Wagner’s music like a true musician, but in so beautiful a manner that seasoned critics quoted the days of Jean de Reszke as the only precedent for this performance. It is said that within ten minutes after the end of Mr. Fontana’s debut in Boston he was signing a contract in Mr. Russell’s office.

Then came Mr. Fontana’s New York success when he created the part of Avito in “The Love of Three Kings” of Montemezzi, whose work was given at the Metropolitan for the first time in America. Seldom has there been such unanimity as characterized the expression of critical opinion that next day. Mr. Fontana, who has not yet a great many roles, is adding to his repertoire as fast as he possibly can, and has elected to return to America for some seasons to come.

Eventful Beginning

But this story, eventful as it is, is not so remarkable as the story of Mr. Ferrari-Fontana’s beginnings on the stage. His birthplace was Rome—1878. He studied medicine, but he was adventurous and the Spring of 1902 found him a secretary in the consular service at Montevideo, some six hours from Buenos Ayres. Quite as a matter of course friends of his who were interested in the theater suggested that he take a small part in a popular farce of the day, and it happened that a song which he sang in the second act was conspicuously successful at each performance. Mr. Fontana asked six months’ leave at the consulate and appeared on the stage more frequently. He played in numerous little comedies at first, and then he appeared in “L’Acrobat,” an opera comique by Louis Ganne, whose “Hans, the Flute Player” he was to make popular in Italy a few years later. He abandoned his consular position and increased his repertoire by such works as “Fra Diavolo,” “La Fille du Regiment,” “Les Cloches de Corneville,” “La Fille de Mme. Angot.” Returning to Italy, he became quickly one of the most popular tenors in light opera. It was he who made known there the tenor roles in such works as the “Waltz Dream,” “The Merry Widow” “The Blue Moon,” “The Fair Lola,” etc.

Bear in mind that he was self-taught. At the Teatro Regio, Turin, he made his debut as Tristan in Wagner’s opera—his first grand opera, if you please—on the 2nd of March, 1910. He had been singing baritone rôles in light opera. He met the baritone Stracciari, who encouraged him to work toward grand opera. Mr. Fontana was finally given a leading rôle in Massenet’s “Hérodiade,” which did not particularly interest him, for his first appearance. In the meantime he listened from the front row, just behind the conductor’s chair, to “Tristan und Isolde,” Serafino conducting: This was the beginning of the end. The conductor watched his face. After an act he turned about in his chair and said, jestingly: “I suppose you would like to sing that opera.”

“Yes,” said Fontana, “I would like to sing it. But I assure you that if I did so I would do a much better piece of work than that one”—indicating the gentleman who had just been occupying the center of the stage.

His First “Tristan”

The capricious fates being in a kindly mood that tenor was taken ill and Ferrari- Fontana was given his chance. He made his debut as Tristan. He went on the stage without an orchestral rehearsal and with complete success. He sang Tristan seven times that season—of course in Italian. Two seasons later he was called “the Italian ‘Tristan.’ He divided his time between Italy and Buenos Ayres, and it was while traveling to Buenos Ayres .that he met Mme. Matzenauer on shipboard and married her after a short and romantic courtship, nineteen months ago.

Having learned Tristan Mr. Fontana mattered much of the Wagnerian répertoire, including “Tannhauser,” “Lohengrin” and “Siegfried.” He learned also the “Norma” and the “Don Sebastiano” of Donizetti. In Boston he added to his repertoire Gennaro in “The Jewe’s of the Madonna,” Samson in Saint-Saëns’s opera, and Canio in “Pagliacci,” and in all these parts he made first appearances here this season. He created the tenor role in “The Love of Three Kings” at the first performance at La Scala, Milan, last season, and his success in the recent New York premiere of this work is still the talk of the town. Mr. Fontana is going to appear soon as Turiddu in “Cavalleria” and next year as José in “Carmen,” Otello in Verdi’s opera, Rhadames in “Aida” and in other roles. He has sung thus far in Rome, Naples, Turin, Milan, Bologna, South America and Boston. He goes from Boston to Milan, thence to Buenos Ayres, and so on.

Mr. Fontana has sung his Tristan in Italian. It was in this language that he sang on the occasion of his début at the Boston Opera House last season. In the interval between that season and this he was requested by Mr. Russell, in accordance with the standards of the Boston Opera, to learn his rôle in German. With Mme. Matzenauer singing—this time as Isolde, for although a contralto her range is such that she is capable of taking either the part of Brangãne or Isolde—he made a distressed appearance, singing stiffly and cautiously in the German tongue until the end of Act II. At that moment, unable to contain himself any longer, Mr. Fontana lapsed back into Italian and immediately was the romantic and golden-voiced interpreter who fitted the Wagner conception.

Loath to Learn It in German

Mr. Fontana remarked that he was very loath to learn the part of Tristan in German. He went further—he had that if Wagner could have heard his music, rid of German gutturals and consonants that chop a legato to pieces, if he could have heard his lyrical masterpiece in Italian he would have rejoiced. “For Italian is music itself, and the wonderfully melodic character of ‘Tristan’ was surely not intended for directly unmelodic treatment. Only the music of the Italian tongue seems to me a fit medium for the transcendental beauty of the Wagner compositions, and I wish that I might spread this gospel over the world. The Italians know it. Do you know that I have sung in 145 performances of ‘Tristan’ since 1910 in Italy? ‘Tristan’ is one of the most popular operas in the Italian repertoire. Many theaters open their seasons with it, and other operas of Wagner are sung with enthusiasm throughout the country. In Bologna I have heard children in the street singing snatches from ‘Tannhäuser.” The first reason for all this is that the music is so emotional and so nobly melodic. And do not forget that Wagner owed several important features of his style to the Italians—especially a characteristic curve of his melody which is found, particularly in ‘Tristan.’”

Mr. Fontana speaks very highly of Montemezzi, whom he knows personally, and “The Love of Three Kings.” He mentioned Montemezzi as among those whose genius gives the greatest future hope for the Italian operatic art. Puccini? He shrugged his shoulders. “I find Montemezzi, of all the younger composers; most distinguished in his invention, and remarkable in his workmanship. You might find in his very rich and complete orchestra a suggestion of Strauss—always with the proviso that, however rich and heavy-laden with effects the score may be, the result of the scoring.is clearness, not complexity of detail, but detail nobly subordinated to the big lines of the whole. As a melodist and a technician Montemezzi is a most gifted and serious young man. His first two operas, full of fine things, were not as successful as ‘L’Amore dei Tre Re’ principally because of the composer’s lack of experience in writing for the stage. But in ‘L’Amore’ Montemezzi has written a masterpiece of the theater. The opera has only to be heard, I think, to make its way.”

Home Life

Shall it be added, that Mr. Ferrari-Fontana, a happy and successful man, a brilliant talker, is a model of what an intelligent artist may be, without fuss or folderol. He adores his wife; his home is the most attractive place that he knows. I have said that he was entirely self-taught. His wife has coached him in many of his late roles, and it was she who helped him over many a thorny spot in the German tongue during the Summer past. There is no thought of artistic rivalry between these two, although both are prominent enough artists to warrant such a traditional attitude. Mutual intelligence and enthusiasm for the work is an additional stimulus to each. Nor is it every husband who has the privilege of singing Tristan to his wife’s Brangäne or lsolde.

Mr. and Mrs. Fontana have not completed their arrangements for the future of Miss Adrienne. One of their three large estates in Italy will go to her. The estates are situate at Rome, Cesnatico and Genoa. “Of course, if there should ever be another little Ferrari-Fontana I suppose we should immediately make out a new will.” The villa at Genoa is situated forty metres from the sea, filled with valuable pictures and statuary, some of it by Ettore Fontana, one of the leading sculptors of Italy, the uncle of Mr. Ferrari-Fontana. There is a living room on one floor as large as the entire floor of the house. There are sleeping chambers which almost jut out over the marvelous blue Italian sea. If we were Miss Adrienne, we know which villa we would choose.

Dinner to Dr. Robyn

Dr. Alfred G. Robyn, the organist and composer, was the guest of honor at the 384th dinner of the Hungry Club of New York, given at the Hotel Marseilles, January 26. Several of Dr. Robyn’s songs were sung by Jane Le Brun, Mary Mason and Ida Cook.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO