100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (176)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (176)

December 30, 1916

Page 5

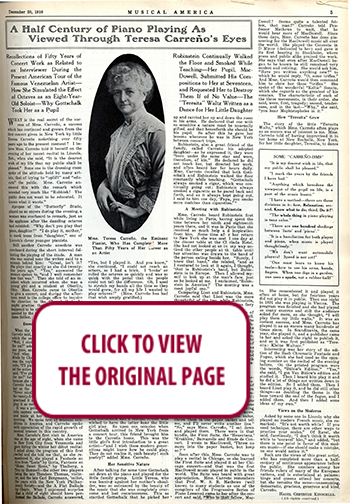

A Half Century of Piano Playing As Viewed Through Teresa Carreño’s Eyes

WHAT is the real secret of the ·success of Mme. Carreño, a success which has continued and grown from the first concert given in New York by little Teresa Carreño something over fifty years ago to the present moment? I believe Mme. Carreño told it herself on the evening of her recent recital in Lincoln, Neb., when she said, “It is the dearest wish of my life that my public shall be pleased.” Someone in the· dressing room spoke of the attitude held by many artists, that of trying to “uplift” and “educate” the public. Mme. Carreño answered this with the remark which sounded very much like “Rubbish! The public does not want to be educated. It knows what it wants.”

Apropos of the “Butterfly” Etude, played as an encore during the evening, a woman was overheard to remark, just as the applause after ·the dazzling octaves had subsided: “Why don’t you play that piece, daughter?” “I do play it, mother,” In meek tones from “daughter,” one of Lincoln’s clever younger pianists.

Still another Carreño anecdote was overheard during the short interval following the playing of the etude. A man who was seated near the writer said to a woman behind him: “Great, isn’t it? She plays that exactly as she did twenty-five years ago.” “Yes,” answered the woman spoken to, “and I well remember how that was.” ‘Then she told of an incident which occurred· when she was a young girl and a student at Oberlin, Ohio. Mme. Carreño came to Oberlin to give a concert, and during the afternoon went to the college office to inquire the direction to the Chapel that she might practice there. The little girl happened to be standing by, and was requested by the registrar to conduct Madame thither.

Encouraged a Youngster

When the Chapel was reached Mme. Carreño said, “Don’t you play some?” to which the embarrassed child answered, “Well, I study.” “What can you play for me!” asked Carreño. “I only know one piece, and I’m just studying that.” “And what is it?” is it?” “The ‘Butterfly’ Etude by Chopin, but I can’t play it,” was the reply. “Then,” answered Carreño, I’ll play it for you,” and she suited the action to the word. “There,” she said, I’ve played for you, now you play for me!” but the little gir1 was crying because she could not play the Etude as Carreño had. The great artist patted her on the shoulder and said simply, “Never mind, I’ve been practicing that for twenty-five years, and when you have practiced it as long as I have you can play it as well as I do.”

It was a privilege to hear Mme. Carreño express some of her views on life and music at her hotel the following morning. We spoke first of musical conditions in America, and Carreño spoke with appreciation of the rapid growth of musical interest in this country. Mme. Carreño’s first visit to America was at the age of eight, when she came to New York City from Venezuela and gave during the winter her debut recital. I asked about the program of this first recital and she l told me that, as she remembered it, she played a Fantasie on Airs from “Lucia” by Goria, Fantasie on “Home Sweet Home,” by Thalberg, a Trio by Bummell—the other two players being the late Theodere Thomas, violinist, and the late Carl Bergmann, ‘cellist, for years with the New York Philharmonic: Society—and the A Flat Ballade by Chopin. When I expressed surprise that a child of eight should have performed the Ballade, Carreño answered, “Yes, but I played it. And you know,” she continued, “I could not reach an octave, so I had a trick. I ‘broke’ or rolled the octaves so quickly and was so quick with the pedal that the people could not tell the difference. Oh, I used to stretch my hands all the time so they would grow, for all my life I wanted to play octaves!” (Mme. Carreño has had that wish amply gratified.)

Her First Medal

Mme. Carreño’s first New York recital was followed by eight or ten others, given within the short period of two months. In these programs she played many other difficult works of the times, including fantasies on airs from “Rigoletto” and “Norma.” At the age of nine she played her first orchestral engagement, playing the Capriccio Brillante by Mendelssohn with the old Boston Philharmonic Society, and on this occasion was presented with her first gold medal by Carl Zerahn, who conducted the orchestra.

Soon after these successful concerts little Teresa Carreño went to Paris with her parents, living there for nearly ten years. Here she played for Liszt, Rubinstein, Gounod, Berlioz, Bizet, Auber and Saint-Saëns. Mme. Carreño spoke feelingly of the splendid advantages she had had in those early days of associating with all those great people. “Oh! I have known them all,” she said. “I am a pianist of two centuries, and I mark the years by the friends I have had.”

Mme. Carreño is very loyal to the memory of Louis Gottschalk, the pianist, who was her teacher. The Carreño family and Gottschalk had a mutual friend who wished to have the latter hear the little girl play. So upon one occasion when Gottschalk arrived in New York from a concert tour, this friend brought him to the Carreño home. This was the little girl’s first introduction to a great artist—and I wish these modern generations might know how he could play. They do not realize it, such beauty! such poetry!” added Mme. Carreño.

Her Sensitive Nature

After talking for some time Gottschalk sat down at the piano and played for the little family group. Little Teresa, who was leaning against her mother’s shoulder, was so entranced by the beauty of the music that she was completely overcome and lost consciousness. This so startled Gottschalk that he picked her up and carried her up and down the room in his arms. He declared that one with so sensitive a nature must be unusually gifted, and that henceforth she should be his pupil. So after this he gave her lessons whenever he was in New York between concert trips.

Rubinstein, also a great friend of the family, called Carreño his adopted daughter—as he expressed it, they were “born under the same star and were, therefore, of kin.” He declared he did not teach her, but directed her work, and often heard her for hours daily. Mme. Carreño recalled that both Gottschalk and Rubinstein walked the floor constantly while teaching. “Gottschalk always smoked a cigar, which was continually going out; Rubinstein always smoked a cigarette as he paced back and forth, and as it always kept· going out, I said to him one day, ‘Papa, you smoke more matches than cigarettes.’”

A Meeting with Rubinstein

Mme. Carreño heard Rubinstein first while living in Paris, having spent the time between her ninth and eighteenth years there, and it was in Paris that she received so much help and inspiration from him. Sometime after her return to New York she was seated one day at the dinner table at the Clarinda Hotel. She had not looked at or in any way noticed the other people at the table until her attention was drawn to the hand of the person eating beside her. “Surely, I know that hand,” she related, “and as I ventured to look at it again, I thought, ‘that is Rubinstein’s hand, but Rubinstein is in Europe. Then I allowed myself to look up at the man’s face, just as he looked at me. I exclaimed, ‘Rubinstein in America?’ The meeting was a most joyful one.”

Comparing Liszt and Rubinstein, Mme. Carreño said that Liszt was the more thoughtful of the two, while Rubinstein, in speech, manner and playing was fiery and impetuous.

Carreño spoke with natural pride of her famous pupil, Edward MacDowell. From the time of Carreño’s return to America from Paris at the age of eighteen her father and mother and the MacDowells were intimate friends. “We were as one family,” said Mme. Carreño. MacDowell was at that time about eight or nine years of age and was a pupil of Carreño. She describes MacDowell as being at that time so sensitive and shy that it was painful to watch him, and she attributed much of his later ill health and early death to this same sensitiveness.

The Modest MacDowell

At the age of fourteen MacDowell, accompanied by his mother, went to Europe for further study. At the age of seventeen he sent to Mme. Carreño, then in America, a roll of manuscript, accompanied by a letter in which he said: “You know I have always had absolute confidence in your judgment. Look these over, if you will. If there is anything there any good, I will try some more, but if you think they are of no value, throw them in the paper basket and tell me, and I’ll never write another line.” “So,” says Mme. Carreño, “I sat down and played them. There were in that bundle, the First Suite, the ‘Hexentanz,’ ‘Erzahlen,’ Barcarolle and Etude de Concert. I wrote to MacDowell, ‘Throw no more into the paper basket, but keep on!’”

Soon after this, Mme. Carreño was to play a recital in Chicago, so she learned the First Suite and played·it at her Chicago concert—and that was the first MacDowell music played in public in the world. The Suite was heard with great appreciation. Mme. Carreño remembers that Prof. W. S. B. Mathews (well known to many students as one of the compilers of the Progressive Series of Piano Lessons) came to her after the concert and said, “Who is that fellow, MacDowell? Seems quite a talented fellow, that man!” Carreño told Professor Mathews to wait, that he would hear more of MacDowell. Since those days, Mme. Carreño has done pioneering for the MacDowell music all over the world. She played the Concerto in D Minor (dedicated to her) and gave it its first hearing in Stockholm, where press and public alike praised the work. She says that even after MacDowell began to be known he still remained very modest and retiring. She would ask him, “Have you written anything new?” to which he would reply, “O, some trifles.” And Mme. Carreño would then command him to show her these “trifles.” She spoke of the wonderful “Keltic” Sonata, which she regards as the greatest of his sonatas. The characteristic of each of the three movements, in their order, she said, were, first, tragedy; second, tenderness, and in the last—“Why,” she said, “you hear Mephistopheles in it.”

How “Teresita” Grew

The story of the little “Teresita Waltz,” which Mme. Carreño often plays as an encore was of interest to me. Mme. Carreño told of having improvised it in her home at New Rochelle, New York, for her little daughter, Teresita, to dance to. She remembered it and played it often at home, but for fourteen years did not play it in public. Then one night in 1891 she was playing in Vienna. The program was finished and she had played so many encores and still the audience asked for more, so she thought, “I will play them my little waltz.” It was an instant success, and Mme. Carreño has played it as an encore many hundreds of times since. In Scandinavia, the same year, she played it, and a publisher came to her and asked the right to publish it, and so it was first published as “Teresita: Kleine Waltzer.”

Interesting was her story of the edition of the Bach Chromatic Fantasie and Fugue, which she had used as the opening number on the recital of the evening before. On the printed program were the words, “Bulow’s Edition.” “Yes,” she said, “I got Von Bulow’s edition and studied it. Then I heard him play it and he did a lot of things not written down in the edition. So I added them. Then I heard Liszt play it, and he did still other things—as doubling the theme in the bass toward the end of the fugue, and I added them. And then I added some ideas of my own.”

Views on the Moderns

Asked by someone in Lincoln why she played no modern French music, she remarked: “It’s not worth while! If you need technique, there are other ways to practice your scales.” Of Ravel, she said, facetiously, “I don’t think it worthwhile to ‘unravel’ him·and added, “but there is one point in favor of this modern music—if one should make a mistake, no one would notice it.”

Such are the views of this great artist, who has completed more than a half century of continuous appearance before the public. She numbers among her friends rulers of many of the European nations, and is entertained at palaces; kings and queens attend her concerts, but she remains the same—unassuming, democratic, gracious, generous and kind, Carreño. —HAZEL GERTRUDE KINSCELLA

SOME “CARREÑO-ISMS”

- •“It is my dearest wish in life, that my public shall be pleased.”

- •“I mark the years by the friends I have had.”

- •“Anything which broadens the viewpoint of the pupil on life, is a part of the music lesson.”

- •“I have a method—there are three divisions in it: first, Relaxation; second, Know what to do; third, Do it!”

- •“The whole thing in piano-playing is tone color.”

- •“There are one hundred shadings between ‘forte’ and ‘piano.’”

- •“It is a humiliation for both player and piano, when music is played thoughtlessly.”

- •“We don’t want automobile players! Speed is not art!”

- •“One must learn to know his tools—how to use his arms, hands; fingers. When one digs in a garden, one uses a spade, not a rubber-ball!”

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO