100 YEARS AGO...IN MUSICAL AMERICA (75)

100 YEARS AGO...IN MUSICAL AMERICA (75)

December 26, 1914

Page 9

STATUS OF THE ‘CELLO AS A SOLO

Never So Strong as Now, Says Pablo Casals, Who Is in America for an Unexpected Tour—Comments on Musical Conditions in America and in Spain

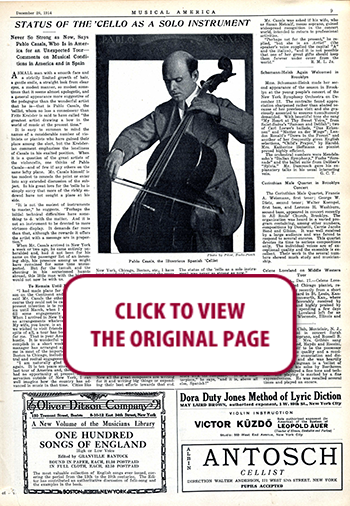

A SMALL man with a smooth face and a strictly limited growth of hair, a gentle smile, a straight look from clear eyes, a modest manner, so modest sometimes that it seems almost apologetic, and a general appearance more suggestive of the pedagogue than the wonderful artist that he is—that is Pablo Casals, the ‘cellist, whom no less a connoisseur than Fritz Kreisler is said to have called “the greatest artist drawing a bow in the world of music at the present time.”

It is easy to summon to mind the names of a considerable number of violinists or pianists who have gained their place among the elect, but the Kreislerian comment emphasizes the loneliness of Casals in his exalted position. When it is a question of the great artists of the violoncello, one thinks of Pablo Casals—and of few if any others on the same lofty plane. Mr. Casals himself is too modest to concede the point or enter into any extended discussion of the subject. In his great love for the ‘cello he is simply sorry that more of the richly endowed have not sought a place at his side.

“It is not the easiest of instruments to master,” he suggests. “Perhaps the initial technical difficulties have something to do with the matter. And it is not an instrument to be devoted to mere virtuoso display. It demands far more than that, although the rewards it offers the artist with a message are in proportion.”

When Mr. Casals arrived in New York a week or two ago, he came entirely unheralded and, had it not been for his name on the passenger list of an incoming ship, his presence among us might have remained for some time unsuspected. But for the tumult and the shouting in his accustomed haunts abroad, this little man with the big bow would not now be with us.

To Remain Until March

“I had made plans for the entire season on the Continent and in England,” said Mr. Casals the other day, “but of course they could not be carried out. My present intention is to remain in America until March, when I shall return to fill some engagements in England. When I arrived in New York I had made no arrangements whatever for a tour. My wife, you know, is an American, and we wished to visit friends here. But, in spite of all, a tour has been mapped out for me. That is your American spirit of hustle. It is wonderful what it can accomplish in a short week or two. My manager has arranged appearances for me in most of the important cities from Boston to Chicago, including both orchestral and recital engagements.

“I am naturally glad to play here again. It is ten years since I made my last tour of America and, though I have had no opportunity at present for observation outside of New York, I can well imagine how the country has advanced in music in that time. Cities like New York, Chicago, Boston, etc., I have long considered in every respect the peers in musical standing of the great European capitals.

“In my two former tours I discovered that American audiences were perhaps too eager for the purely virtuoso performance, too prone to regard the pyrotechnicist with a fonder eye than they would have for the man with a true musical message. I was sorry that was so, but I am sure that Americans today have outgrown that attitude in large measure and are able to look beyond mere externals and to discount empty brilliancy in favor of the deeper things that proceed from the soul of the composer and his interpreter.

Status of ‘Cello

“As to the ‘cellist, if he have something to say, I am sure he will find a more responsive audience to-day than ever before. There was a time, up to the last ten years or so, when the ‘cello was looked upon more or less as a salon instrument and the sort of music that was written for it was salon music. Now all the great composers are writing for it and writing big things or expending their best efforts towards that end. The status of the ‘cello as a solo instrument was never so strong as now.”

Of musical conditions in his native Spain, Mr. Casals has naturally been a keen observer, though most of his activities of late years have taken him to other lands. Spain’s musical awakening in the last decade is a subject he is fond of discussing. The progress in chamber and choral music—every town of consequence now has its chamber music societies, and even the little villages of 300 inhabitants, as a result of the labors of men like Clavé and Morera, have their choral organizations—particularly interests him as an encouraging sign of the times. The school of opera in Spain, too, though its influence has not yet extended to the outside world, is making healthy progress and evolving into a truly national art instead of an imitation of Puccini and Mascagni—artistic bêtes noires of Mr. Casals. Of the opera, “Goyescas,” by Granados, which its composer has developed from his Suite for Piano and which was to have had a première in Paris this Winter, Mr. Casals has high hopes. He has gone over the score with the composer. “It is a masterpiece,” he says, “and it is, above all else, Spanish!”

Mr. Casals was asked if his wife, who as Susan Metcalf, mezzo-soprano, gained widespread recognition in the concert world, intended to return to professional activities. “Perhaps not for the present,” he replied, “but she is an Artist” (the speaker’s voice supplied the capital “A” and the italics), “and it is not possible that one of her great gifts should keep them forever under cover from the world.” —R. M. L, JR.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO