100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (258)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (258)

September 28, 1918

Page 9

REPORTS FINE ARTS FLOURISHING IN “RED RUSSIA”

Serge Prokofieff, Much-Discussed Ultra-Modern Russian Composer, Now in New York, Tells of Conditions Under Bolsheviki—Latter Paying Big Salaries to Noted Artists, Bringing Out New Musical and Dramatic Works in Sumptuous Style, and Regard Artists with Favor—Contemporary German Music Still Barred—Rachmaninoff’s Estate Burned and Plundered by Those in Power—Music Paper as Valuable as Paper Currency—Mr. Prokofieff’s Standing, Works and Plans

By FREDERICK ·H. MARTENS

OUT of the topsyturvydom of the Bolshevist Russia, from Petrograd by way of Siberia, Japan and San Francisco, there has just arrived in New York one of the leading figures in ultra-modern Russian composition, Serge Prokofieff. A pupil of Glière, Rimsky-Korsakoff and Liadoff in composition, he has already blazed new musical creative trails on his own account, and in his own land is hailed as the peer of Stravinsky, ‘Rachmaninoff, Medtner and others of the little group which represents the last word in Russian music.

He is not known only in Russia. Montagu-Nathan, who, in 1913, accorded him only brief mention in his “History of Russian Music,” devoted an extended, enthusiastic article to him in the London Musical Times the year following, speaking of him as “young Prokofieff, who has tweaked the ear of the pedagogue and warmed the cockles of the progress progressive musician’s heart.” And· Montagu-Nathan found amusement in the thought that this “Rubinstein prize winner (Petrograd Conservatory), triumphant virtuoso, composer and performer of fine piano concertos and ambitious sonatas, this symphonist, the trump card of Siloti, Diaghileff’s latest find [Prokofieff had just completed a new ballet for the 1915 Russian season in Paris and London; a season which was one of the earlier victims of the war], whose ‘Scythian Suite’ drove Glazounoff from the hall in which it was being performed, this ‘futurist,’ ‘barbarian,’ enfant terrible [echo seems to answer “Ornstein”!] was introduced to a London promenade audience as the composer—of an inoffensive Scherzo for four bassoons!”

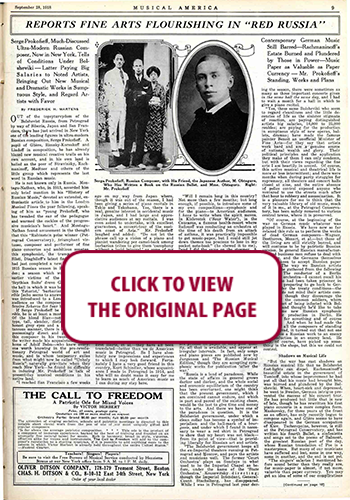

If Serge Prokofieff be an enfant terrible, he is at least a most engaging one. Of the blond Slav—not Turko-Slav—type, tall, slender, distinguished, with honest grey eyes and a forceful, spontaneous manner, there is something prepossessingly direct and genuine about this composer in his twenties. When the writer made his acquaintance at the home of Adolf Bolm—who knew everyone worth knowing in the pre-revolutionary Petrograd world of art and music, and to whom temporary exiles from what might now be called “Unholy Russia”: naturally gravitate when they reach New York—he found no difficulty in inducing Mr. Prokofieff to talk of present-day musical conditions in his native land.

“I reached San Francisco a few weeks ago on my way from Japan where, though it was out of the season, I had been giving a series of piano recitals in Tokio and Yokohama. Yes, there is a real, genuine interest in occidental music in Japan, and I had large and appreciative audiences at my recitals. I was even asked to undertake, with excellent guarantees, a concert-tour of the eastern coast of Asia.” Mr. Prokofieff laughed and added: “Do not let the phrase call up a vision of a piano and pianist wandering per camel-back among barbarian tribes to give them ‘cacophony without a lucid interval,’ as some of my earlier compositions have been called. Not at all; the concerts were to be given in Shanghai, Hong-Kong, Manila—places in which there are large English and American colonies—in Batavia and Surabaya. These Javanese cities are especially music-loving, and I know of two Russian artists who gave a splendidly successful series of sixty recitals in Java during the season preceding my arrival in Japan.

Eager to Know Our Music

“I did not see my way clear to undertake the proposed Asiatic concert-tour,” continued Mr. Prokofieff. “I am a natural-born traveler, and though I enjoyed immensely my two months in Japan, and met a number of interesting people, I wanted to see the United States, listen with an open ear and mind to American music, and meet American musicians. You see, we know American literature—Poe, Mark Twain, Holmes, Bret Harte, et al.—they have all been translated—better than we do American music in Petrograd. So I have absolutely new impressions and experiences to which I may look forward. Fortunately I have a very good friend in this country, Kurt Schindler, whose acquaintance I made in Petrograd in 1914, and who will no doubt make it easy for me to learn as much of American music as I can during my stay here.

“Will I remain long in this country? Not more than a few months; but long enough, if possible, to introduce some of my own compositions—symphonic and for the piano—to American audiences. I have to write when the spirit moves. In Kislovotsk (‘Sour Water’), in the Caucasus, a famous health-resort where Safonoff was conducting an orchestra at the time of his death from an attack of asthma, it was practically impossible to get music-paper, but I could still jot down themes too precious to lose in my pocket note-book” (he showed it to me), “and I did the same on the steamer. A theme is an elusive thing—it comes, it goes, and. sometimes it never returns. Some of my critics might say, no doubt” (his eyes twinkled), “that the more themes of mine which never returned the better!”

Musical Criticism in Russia

“Music criticism—serious, valid critical study and analysis of new compositions—is really on a high level in Russia. Our critics in Petrograd and Moscow are scholars, savants, men of distinguished literary and scientific attainment who have specialized in music, such as V. G. Karatygin, professor of history at the ci-devant Imperial Academy of Music in Petrograd, Igor Gleboff, Victor Belaieff. They lay stress on the musical, not the personal equation, in their critiques. And even now we have some splendid music magazines—the Petrograd Melos and Musica, though they, as well as such music as is still published, are printed on paper of very poor quality, all that is available, and appear at irregular intervals. In fact, only songs and piano pieces are published now. By Jurgenson and ‘The Russian Musical Edition,’ though they are accepting symphonic works for publication after the war.’

“Russia is a land of paradoxes. While the state of affairs in general grows darker and darker, and the whole social and economic equilibrium of the country has been overturned, one might think that the present government which I am convinced cannot endure, and which is part and parcel of the existing chaos, would be the last to give time and money to the arts. And there we have one of the paradoxes in question. It is the Bolshevist government, under which a clean collar has become a symbol of imperialism and the hall-mark of a bourgeois, and under which I found it necessary to wear a red shirt in Petrograd to show that my heart was not black from its point of view—that is providing liberally for Russian art and artists.

“The Bolshevist government keeps all the ex-Imperial theaters running in Petrograd and Moscow, and pays the artists and musicians well. The former ‘Court Orchestra’ plays on Sundays in what used to be the Imperial Chapel as before, under the name of the ‘State Orchestra,’ Koussevitsky directing, though the Imperial Intendant, General Count Stachelberg, has disappeared. While I was in Petrograd last year· during the season, there were sometimes as many as three important concerts given in the same hall the same day, and I had to wait a month for a hall in which to give a piano recital.

“Yes, these same Bolsheviki who seem to regard cleanliness and the little decencies of life as the sinister stigmata of reaction, are paying distinguished artists big salaries, 10,000 to 25,000 rubles; are paying for the production in sumptuous style of new operas, ballets, dramas; have made the famous painter Benoit an unofficial Minister of Fine Arts—for they say that artists work hard and are a genuine source of national wealth and glory. Their political principles and the application they make of them I can only condemn, but with their views regarding the fine arts I am heartily in accord. Of course, this active musical and theatrical life is more or less intermittent; and there were months when during party struggles for supremacy, all theaters and concert halls closed at nine, and the entire absence of police control exposed anyone who ventured to use the streets much after that hour to robbery and assassination. It is a pleasure for me to think that the very valuable library of old music, much of it in me, at the Petrograd Conservatory, has been safely removed to various central towns, where it is preserved.

“Of course, at the beginning of the war no German music whatever was played in Russia. We have now so far relaxed this rule as to perform the works of dead German composers—Wagner, Beethoven, Mozart, et al.—but those of the living are still strictly barred, and will continue to be by patriotic Russian opinion. In general Russian manufacturers and business men refuse to deal with Germany, and the Germans themselves are not keen to accept Russian paper money. The way we Russian artists feel may be gathered from the following incident. The conductor of a Berlin symphony orchestra—l cannot recall his name—who had been taken prisoner in 1915, was preparing to go back to Germany under the treaty conditions—the Germans do not mind their artists coming back, though they discourage the return of the common soldiers, whom they suspect of being infected with Bolshevism—and thought he’d like to take along some new Russian symphonic works for production in Berlin. He asked me for something and of course I refused. And when he had made the rounds of all the composers of standing in Petrograd, it turned out that not one would give a Russian work to an enemy for production in an enemy land. He may, of course, have picked up something in the shops, but this we could not control.

Shadows on Musical Life

“But the war has cast shadows on Russian musical life that no Bolshevist footlights can dispel. Rachmaninoff’s beautiful estate in the government of Tomboff, into whose improvement he had put all that his music had brought him, was burned and plundered by the Bolsheviki. When, heart-sick and depressed, he went to Sweden, German intrigue prevented the success of his concert tour. He has produced but little that is new of late, though he has rewritten his first piano concerto in a more complex form. Maskovsky, for three years at the front as an officer, has only recently begun to compose again, and Glière seems to have disappeared in the German occupation of Kiev. Tscherepnine, however, is still at the Petrograd Conservatory, and has written his fourth Ballet, a sinfonietta and songs set to the poems of Balmont, the greatest Russian poet of the day, whose Russian translation of Poe is a masterpiece. But many of our musicians have suffered and lost, some in one way, some in another, and the end is not yet.

“The singers’ salaries I mentioned before sound better than they really are, for music-paper is almost, if not more, valuable than paper currency. You may get an idea of some of our complications when I tell you that any number of provincial towns and cities have established their own mints and issue money guaranteed by the town. Press is really the word, not mint, for all gold and silver money went promptly into hiding at the beginning of the war. So urgent was the need of currency, and so hard was it to get skilled workmen, that the municipal authorities sent to Siberia for counterfeiters, who were set to work making good money under armed guards. Sounds like opéra comique, does it not? Another amusing paradox is that the peasants in general prefer the bank-notes of the ex-Imperial currency to those issued by the present de facto government; and the repudiated money of the dead and gone régîme circulates at a premium!

“My own compositions? I cannot well praise them myself, but I can tell you what they are. And I think you will have an opportunity to judge some of them when I give my orchestra concert and recitals here. I have written piano sonatas, violin sonatas, two concertos for piano and one for violin, songs, piano pieces, among them my collection of ‘Sarcasmes’ and the twenty miniatures, ‘Moments Fugitifs.’ Then there are two symphonic poems, ‘Dreams’ and ‘Autumn’; my ‘Scythian Suite’, which was received in Petrograd in the same way Stravinsky’s ‘Sacre’ was in Paris (I’ll be curious to know how it will be received here); several operas, the latest, ‘The Gambler’ after Dostoevski, in four acts, accepted for the Imperial Theaters of Moscow and Petrograd; a ballet, ‘Harlequin’s Story,’ for the Russian ballet-season in Paris of 1915—unfortunately both the Russian season of that year and the ‘Imperial’ theaters came to be non-existent—and my last work, ‘The Conjuration of the Seven,’ for chorus, solos and orchestra, set to Balmont’s poetic version of an ancient Assyrian cuneiform hymn, dealing with the · conspiracy of the seven evil spirits of the fall and winter months, against the five good spirits of the others—a wonderful text!

“That is an outline of my work as a composer—you can fill it in with criticism when you hear some of my things played.” And that this music will be worth hearing may be inferred by the dictum of the eminent Russian critic Karatygin, who says: “It is from Serge Prokofieff, more than from any other, that we must expect to hear a new language in musical art, one more deep, comprehensive and individual!”

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO