100 YEARS AGO...IN MUSICAL AMERICA (111)

100 YEARS AGO...IN MUSICAL AMERICA (111)

September 18, 1915

Page 6

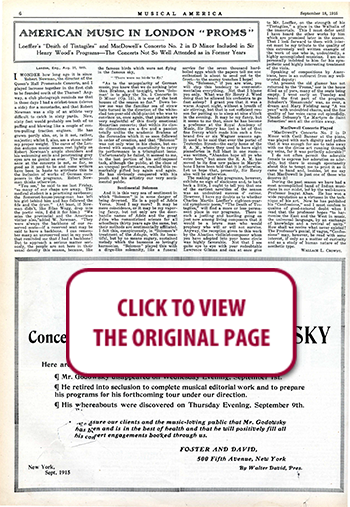

AMERICAN MUSIC IN LONDON PROMS

Loeffler’s “Death of Tintagiles” and MacDowell’s Concerto No. 2 in D Minor Included in Sir Henry Wood’s Programs—The Concerts Not So Well Attended as in Former Years

BOSTON, April 4.

I WONDER how long ago it is since Robert Newman, the director of the Queen’s Hall Promenade Concerts, and I played lacrosse together in the first club to be founded south of the Thames? Anyway, a club photograph reminds me that in those days I had a cricket-team (eleven a side) for a moustache, and that Robert Newman was a slip of an athlete very difficult to catch in sixty yards. Now, sixty feet would probably see both of us puffing and blowing like a couple of contra-pulling traction engines. He has grown portly also, or, is it not, rather, majestic; whilst I, alas, am a stone under my proper weight. The cares of the London autumn music season rest lightly on Robert Newman’s ample shoulders and his welcoming smile and penetrating grey eyes are as genial as ever. The attendance at the concerts is not, so far, so good as it used to be and some writers have been in haste to attribute this to the inclusion of works of German composers in the programs. Robert Newman thinks otherwise.

“You see,” he said to me last Friday, “so many of our chaps are away. The medical student is a practising sawbones; the Somerset-house-young-roan has left his girl behind him and has followed the fife and the drum.” (At least, if Newman didn’t, like Silas Wegg, drop into the poetic vein, I did it for him.) “We miss the provincial and the American visitor also,” added W. Newman. “They were always the backbone of our reserved seats—if a reserved seat may be said to have a backbone. I can remember many an unreserved seat in my youth that reminded me that I had a backbone! But to approach a serious matter seriously, the people are not here in their usual density this season, because, like the famous birds which were not flying in the famous sky, “

‘There were no birds to fty.’

“As to the unpopularity of German music, you know that we do nothing later than Brahms, and to-night, when ‘Soloman’ is to play the No. 1 Concerto in D Minor (Op. 15), it is one of the best houses of the season so far.” Down below me was the familiar sea of straw hats turned in the direction of the white-clad ten-year-old child-pianist who was to convince us, once again, that pianists are very neglectful of this finely emotional Mozartian concerto; that within its classic dimensions are a fire and a passion totally unlike the academic Brahms of the Serenades which it so soon followed in order of creation, and that “Solomon” was not only wise in his choice, but endowed with enough masculinity to carry its performance to a triumphant issue. Unfortunately he failed, it seemed to me, in the last portion of his self-imposed task, although the public, at the close of an unequal performance, recalled this remarkably gifted boy again and again. He has obviously conquered with his youth and his artistry our very sentimental public.

Sentimental Solomon

And it is this very sea of sentiment in which “Solomon” is in some danger of being drowned. He is a pupil of Adèle Verne. Need I say more? It may be mere coincidence, or it may be my vaporing fancy, but not only are the door-handle names of Adèle and the great Jules who romanticised science for all schoolboys thirty years ago the same, but their methods are sentimentally affiliated. I felt this, conspicuously, in “Solomon’s” treatment of the Adagio, with its beautiful, but by no means sugary, sustained melody which the bassoons so lovingly harmonize. “Solomon” played this with a dirge-like solemnity, like a funeral service for the seven thousand hardboiled eggs which the papers tell me one enthusiast is about to send out to the front—to the enemy trenches I hope!

No, “Solomon,” if you are wise, you will stop this t endency to over-sentimentalize everything. Not that I blame you only. What was Sir Henry J. Wood doing that he allowed his orchestra to go fast asleep? I grant you that it was a warm August night, without a breath of air stirring, but that is not sufficient rea son for putting us to sleep at nine o’clock in the evening. It may be my fancy, but it seems to me that, since he has become a professor at the Royal Academy of Music, Sir Henry has lost a lot of that fine frenzy which made him such a firebrand five or six Wagner seasons ago. It used to be said that over the portal of Teuterden Street—the early home of the R. A. M., where they used to have eight pianofortes in full blast in one room—was written, “Abandon hope all ye who enter here,” but since the R. A. M. has moved to its fine new palace in Marylebone I have been told that it is otherwise. Let us hope that, presently, Sir Henry also will be otherwise.

The making of his programs, however, exhibits no sign of slackness and, to hark back a little, I ought to tell you that one of the earliest novelties of the season was an undoubted success d’estime. However, I have my doubts as to whether Charles Martin Loeffler’s eighteen-year-old symphonic poem, “The Death of Tintagiles,” will find a more or less permanent place in our programs. There is such a jostling and hustling going on just now among living composers that it would be a brave man who would prophecy who will or will not survive. Anyway, the reception given to this work by the Alsatian violinist-composer whom you have adopted into your home circle was highly favorable. Not that I see quite eye to eye with your redoubtable Lawrence Gilman and can at once give to Mr. Loeffler, on the strength of his “Tintagiles,” a place in the Walhalla of the immortals. This I must defer until I have heard the other works by him which are promised later in the season. That I look forward to them with interest must be my tribute to the quality of this extremely well written example of the work of one who is, undoubtedly, a highly accomplished musician. I am also personally indebted to him for his sympathetic and highly interesting treatment of the viola.

Speaking of compositions by Americans, here is an outburst from my well-trusted deputy:

“At present the old glamor has not returned to the ‘Proms,’ nor is the house filled as of yore, many of the seats being empty. I went early on Tuesday and heard the first part of the program. Schubert’s ‘Rosamunde’ was, as ever, a dream and Mary Fielding sang “A vos yeux” with undoubted charm, and the fine quality of her voice came out splendidly. Claude Debussy’s ‘Le Martyre de Saint Sebastien’ sent all the critics away.

MacDowell Concerto Played

“MacDowell’s Concerto No. 2 in D Minor with Cecil Banner at the piano, was played with such dignity and pathos that it was enough for me to take away with me the divine art running through my veins, for it was perfectly adorable!”

I do not often permit the adorable female to express her adoration so adorably, but there is enough spontaneity about this to tempt me to print it as it came to hand and, besides, let me say that MacDowell is just one of those who deserve it!

During the past season we have had a most accomplished band of Indian musicians in our midst, led by the well-known Professor Inayat Khan. He has won a wide reputation as a virtuoso in the technique of his art. Now he has published his “Confessions,” and I must confess to qualms of good-natured doubt when I read that the professor hopes “to harmonize the East and the West in music, the universal language, by an exchange of knowledge and a revival of unity.” How shall we revive what never existed? The Professor’s genial, if vague, “Confessions” may, however, be read with some interest, if only as a matter of curiosity and as a study of human nature of the aesthetic type. —WALLACE L. CROWDY.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO