100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (206)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (206)

July 21, 1917

Page 21

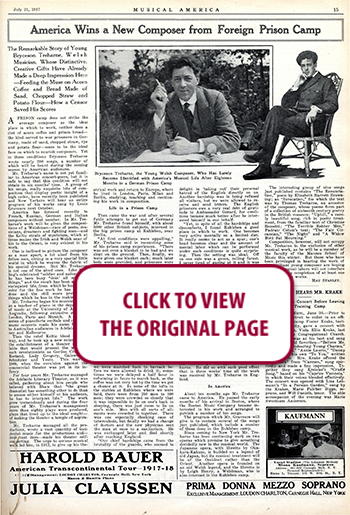

America Wins a New Composer from Foreign Prison

The Remarkable Story of Young Bryceson Treharne, Welsh Musician, Whose Distinctive, Creative Gifts Have Already Made a Deep Impression Here—Feeding the Muse on Acorn Coffee and Bread Made of Sand, Chopped Straw and Potato Flour—How a Censor Saved His Scores

A PRISON camp does not strike the average composer as the ideal place in which to work, neither does a diet of acorn coffee and prison bread—the kind served to war prisoners in Germany, made of sand, chopped straw, rye and potato flour—seem to be the ideal fare on which to nourish composers. Yet in these conditions Bryceson Treharne wrote nearly 200 songs, a number of which will be heard during the coming season by American audiences.

Mr. Treharne’s name is not yet familiar to American concert-goers, but it is safe to say that this condition will not obtain in six months’ time. A group of his songs, really exquisite bits of composition that display poetic insight of a high order, have recently been published and New Yorkers will hear an entire program of his works sung by Louis Graveure next October.

America has listened recently to French, Russian German and Italian composers without number. In Mr. Treharne’s work will be given the compositions of a Welshman—race of poets, musicians, dreamers and fighting men—and the Keltic strain of mysticism, which at times makes the Irish and Welsh near of kin to the Orient, is very evident in his work.

One is inclined to picture the composer as a man apart, a bit aloof from his fellow men, sitting in a very special little world in which he weaves the fabric of his special dreams. But Mr. Treharne is not one of the aloof ones: Like Kipling’s celebrated “soldier and sailor, too,” he has been busy “doin’ all sorts of things,” and the result has been a highly variegated life, from which he has drawn color for the fine work he has already done and the still more pretentious things which he has in the making.

Mr. Treharne began his musical career as a teacher of piano in the department of music at the University of Adelaide, Australia, following extensive study in London, Paris and Munich. A notable series of pianoforte recitals and chamber music concerts made his name familiar to Australian audiences in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne.

Then the rebel Keltic blood had its way, and he took up a new enterprise—the establishment of a theater in Adelaide that would present the work of such revolutionists as Gordon Craig, of Rostand, Lady Gregory, Galsworthy, Schnitzler and Yeats. This was in 1908, when the revulsion against the commercial theater was yet in its infancy.

For four years Mr. Treharne managed the Adelaide Literary Theater, as it was called, gathering about him people who believed with Shaw that “the great dramatist has something other to do than to amuse either himself or his audience, he has to interpret life.” The work grew tremendously and during the four years of Mr. Treharne’s management more than eighty plays were produced, plays that lived up to the ideal sought—of making the theater a temple of aspiration.

Mr. Treharne managed all the productions, wrote a vast quantity of incidental music for the productions and—important item—made his theater self-supporting. The urge to serious musical work led him, in 1912, to give up his theatrical work and return to Europe, where he lived in London, Paris, Milan and Berlin, studying, teaching and continuing his work in composition.

Life in a Prison Camp

Then came the war and after several futile attempts to get out of Germany Mr. Treharne found himself, with about 5000 other British subjects, interned in the big prison camp at Ruhleben, near Berlin:

“At first conditions were appalling,” Mr. Treharne said in recounting some of his prison camp experiences. “There was not even a blanket to be had and we slept on the ground. Then, finally, we were given one blanket each; much later beds were provided, and prisoners were allowed to receive packages of food from home, but for the first six months we subsisted largely on acorn coffee—without milk and sugar—and prison bread. It was not the regulation ‘war bread,’ which is largely composed of rye and potato flour, but contained chopped straw and sand, to which the rye and potato flour was added. The sand got in one’s teeth in shocking fashion,” he added reminiscently.

“Why the sand?” was the very natural question asked.

“Because, to comply with the requirements of international law, the bread served to prisoners had to be of a standard weight," was the answer. “And the straw was added for bulk.”

“Once a week we got rice, for which we were very grateful, but the greater part of our meals consisted of the acorn coffee, prison bread and soup made from boiled cabbage or turnips; meat was a rarity. We were marched ·down to the kitchens to get our portion of acorn coffee at seven o’clock in the morning, then we were marched back to barrack before we were allowed to drink it; sometimes we were delayed a half hour in reforming in fours to march back, so the coffee was not very hot by the time we got a chance at it. In some of the lofts in the stables at Ruhleben where we were held, there were from 250 men to 300 men ; they were crowded so closely that it was impossible to lie on one’s back in sleeping, there was just room to lie on one’s side. Men with all sorts of ailments were crowded in together. There was one especially shocking case of tuberculosis, but finally we had a change of doctors and the new physician sent the man at once to a sanitarium. He was exchanged later and died shortly after reaching England.

“Our chief hardships came from the brutality of the guards, who seemed to delight in ‘taking out’ their personal hatred of the English directly on us. Another hardship was in being refused all visitors, but we were allowed to receive and send letters. The English prisoners owe a very real debt of gratitude to Ambassador Gerard, for conditions became much better after he interested himself in our behalf.

“Yet, in spite of all the hardships and discomforts, I found Ruhleben a good place in which to work. One becomes very active mentally on a limited diet. It really seems to act as a spur; one’s head becomes clear and the amount of mental labor which can be performed under such conditions is quite surprising. Then the setting was ideal. Off on one side was a green, rolling forest. I never tired of gazing at it and it was no end of an inspiration to composition.”

When it is remembered that Mr. Treharne composed nearly two hundred songs while in the prison camp, in addition to several orchestral pieces and the score of one act of a Japanese opera—which is still incomplete—it will be seen that his contention regarding a limited diet has good grounds.

“We had plenty of music in camp at all times,’’ he said. “A really fine orchestra was organized among the prisoners and we gave many concerts; once we presented the ‘Messiah’ with a male choir, a very interesting innovation.”

The rigors of eighteen months of prison camp life caused a complete physical collapse, and Mr. Treharne was included in a list of 150 men sent out at the time an exchange of prisoners was effected. He went to the censor with the precious manuscript of his work—as no prisoner was allowed to take out papers of any description—and the censor promised to use his influence to get the manuscript through to Mr. Treharne. He did so with such good effect that in three weeks’ time all the work was received by Mr. Treharne in England.

In America

About ten months ago Mr. Treharne came to America. He passed the early months of his arrival in Boston, where the Boston Music Company became interested in his work and arranged to publish a number of his songs.

The program which Mr. Graveure will give is to contain several of the songs just published, which include a number of those done in the Ruhleben camp.

Since coming to New York Mr. Treharne has been continuing work on two operas which promise to give something decidedly new to the musical world. The Japanese opera, with libretto by Oka-kura-Kakuzo, is builded on a legend of old Japan, but its musical treatment will be of the Occident rather than the Orient. Another opera is founded on an old Welsh legend, and the libretto is by Leigh Henry, a Welshman, who is also interned in the Ruhleben camp.

The interesting group of nine songs just published contains “The Renunciation,” poem by Elizabeth Barrett Browning; an “Invocation,” for which the text was by Thomas Treharne, an ancestor of the composer, whose poems form part of a collection of sixteenth century poetry in the British museum; “Uphill,” a rarely beautiful song, rich in poetic treatment, from the familiar text of Christine Rossetti; “The Terrible Robber Men,” Padraic Colum’s text; “The Fair Circassian,” “The Night” and “A Widow Bird Sat Mourning.”

Composition, however, will not occupy Mr. Treharne to the exclusion of other musical work, as he will be a member of the faculty of the Mannes School of Music this winter. But those who have been privileged in hearing the work of this brilliant young composer are hoping that pedagogical labors will not interfere with the early completion of at least one of his operatic works. —MAY STANLEY

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO