100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (199)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (199)

June 23, 1917

Page 13

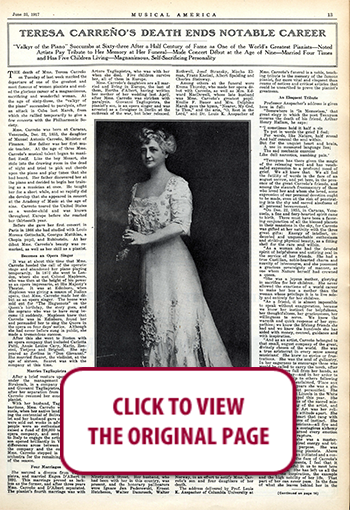

TERESA CARREÑO’S DEATH ENDS NOTABLE CAREER

“Valkyr of the Piano” Succumbs at Sixty-three After a Half Century of Fame as One of the World’s Greatest Pianists—Noted Artists Pay Tribute to Her Memory at Her Funeral—Made Concert Debut at the Age of Nine—Married Four Times and Has Five Children Living—Magnanimous, Self-Sacrificing Personality

THE death of Mme. Teresa Carreño on Tuesday of last week marked the departure of one of the greatest and most famous of women pianists and ended the glorious career of a magnanimous, sacrificing and wonderful woman. At the age of sixty-three, the “valkyr of the piano” succumbed to paralysis, after an attack in Cuba last March, from which she rallied temporarily to give a few concerts with the Philharmonic Society.

Mme. Carreño was born at Caracas, Venezuela, Dec. 22, 1853, the daughter of Manuel Antonio Carreño, Minister of Finance. Her father was her first music teacher. At the age of three Mme. Carreño’s musical talent began to manifest itself. Like the boy Mozart, she stole into the drawing room in the dead of night and tried to pick out chords upon the piano and play tunes that she had heard. Her father discovered her at the piano and decided to begin her training as a musician at once. He taught her for a short while, and so rapidly did she develop that she appeared in concert, at the Academy of Music at the age of nine. Carreño toured the United States as a wonder-child and was known throughout Europe before she reached her thirteenth year.

Before she gave her first concert in Paris in 1866 she had studied with Louis Moreau Gottschalk, Georges Matthias, a Chopin pupil, and Rubinstein. At her debut Mme. Carreño’s beauty was remarked, as well as her skill as a pianist.

Becomes an Opera Singer

It was at about this time that Mme. Carreño heeded the call of the operatic stage and abandoned her piano playing temporarily. In 1872 she went to London where she met Colonel Mapleson, who was then at the height of his power as an opera impresario, at His Majesty’s Theater. It was at Edinboro, when Mapleson was giving a season of Italian opera that Mme. Carreño made her début as an opera singer. The house was sold out for “The Huguenots” on the Queen’s birthday, the story goes, and the soprano who was to have sung became ill suddenly. Mapleson knew that Carreño was in Edinboro, found her and persuaded her to sing the Queen in the opera on four days’ notice. Although she had never before sung in public, she made a tremendous success.

After this she went to Boston with an opera company that included Carlotta Patti, Annie Louise Cary, Mario, Ronconi, Tietjens and Brignoli. She appeared as Zerlina in “Don Giovanni.” She married Sauret, the violinist, at the age of sixteen. Sauret was with the company at this time.

Marries Tagliapietra

After a brief venture upon the stage, under the management of Maurice Strakosch, in a company with Brignoli and Giovanni Tagliapietra, her husband after her separation from Sauret, Mme. Carreño resumed her concertizing as a pianist.

With her husband, Tagliapietra, the baritone, Mme. Carreño went to Venezuela, when her native land was celebrating the centennial of Bolivar. The pianist and her husband gave concerts which were sold out weeks in advance, and the people were so enthusiastic that they raised a fund of $20,000 to establish an opera company, and· sent Tagliapietra to Italy to engage the artists. The season opened brilliantly in Venezuela, but differences arose between members of the company and the conductor, and Mme. Carreño stepped in to direct the orchestra for the remaining three weeks of the season.

Four Marriages

She secured a divorce from Tagliapieltra, and married Eugen D’Albert in 1892. This marriage proved as luckless as the former, and after three years Mme. Carreño and D’Albert separated. Tile pianist’s fourth marriage was with Arturo Tagliapietra, who was with her when she died. Five children survive her, all of them in Europe.

Mme. Carreño’s daughters are all married and living in Europe, the last of them, Hertha d’Albert, having written her mother of her wedding last April, after Mme. Carreño was stricken with paralysis. Giovanni Tagliapietra, the pianist’s son, is an opera singer and was arrested as a foreigner in Berlin at the outbreak of the war, but later released. The eldest daughter, Teresita Carreño, is now giving concerts in London.

Noted Pallbearers

The funeral of Teresa Carreño, who in private life was Mrs. Arturo Tagliapietra, was held on Thursday, June 14, from her late home in the Della Robbia Apartments, at West End Avenue and Ninety-sixth Street. Her husband, who had· been with her in this country, was present, and the honorary pallbearers were Ignace Jan Paderewski, Ernest Hutcheson, Walter Damrosch, Walter Rothwell, Josef Stransky, Mischa Elman, Franz Kneisel, Albert Spalding and Charles Steinway.

Among others at the funeral were ·Emma Thursby, who made her opera début with Carreño, as well as Mrs. Edward MacDowell, whose late husband was Mme. Carreño’s greatest pupil. Emilie F. Bauer and Mrs. Delphine Marsh gave the hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee,” and the aria, “0, Rest in the Lord,” and Dr. Louis K. Anspacher of Columbia read a service for the dead.

Dr. Anspacher remarked on the great span of years of Mme. Carreño’s public career. Though sixty-three at her death, she had been a half century on the concert platform, and she played in the White House to Abraham Lincoln, and last year to President Wilson. Ernest Urch cabled to the composer, Sinding, in Norway, in an effort to notify Mme. Carreño’s son and four daughters of her death.

The address delivered by Prof. Louis K. Anspacher of Columbia University at Mme. Carreño’s funeral is a noble, touching tribute to the memory of the famous pianist, far more vital and eloquent than reams of notices and critical articles that could be unearthed to prove the pianist’s greatness.

An Eloquent Tribute

Professor Anspacher’s address is given here in full:

“Somewhere in ‘In Memoriam,’ that great elegy in which the poet Tennyson mourns the death of his friend, Arthur Henry Hallam, he says:

“‘I sometimes hold it half a sin

To put in words the grief I feel;

For words, like Nature, half reveal

And half conceal the soul within.

But for the unquiet heart and brain,

A use in measured language lies;

The sad mechanic exercise

Like dull narcotics, numbing pain.’

“Tennyson has there given the magic of the releasing word and has vouchsafed expression to a profound mood of grief. We all know that. We all feel the futility of words in the face of an august sorrow, and yet here, in the presence of the great Carreño’s friends, and among the staunch freemasonry of those who loved her and whom she loved, some expression of our personal devotion ought to be made, even at the risk of penetrating into the shy and sacred aloofness of all personal bereavement.

“On Dec. 22, 1853, in Caracas, Venezuela, a fine and fiery-hearted spirit came to birth. There must have been a favoring conjunction of all the blessed planets in their mansions in the sky, for Carreño was gifted at her nativity with the three great gifts: Energy of intellect, undaunted and unquenchable enthusiasm and striking physical beauty, as a fitting shell for the rare soul within.

“As a woman she had the devoted spirit of helpfulness and untiring zeal in the service of her friends. She had a true Castilian, noble-hearted charm and suavity of intercourse, and she possessed a gracious sovereignty of manner, as one whom Nature herself had crowned a queen.

“She was a joyous mother, glorying in sacrifice for her children. She never allowed the ·exactions of a world career to make her less a mother than the woman whose privilege it is· to live solely and entirely for her children.

“As a friend, it is almost impossible to speak without exaggeration, because we know her instinct for helpfulness, her thoughtfulness, her graciousness, her willingness to serve. We know the warmth and quick response of her sympathies; we know the lifelong friends she had and we know the hundreds she has aided with money, counsel, guidance and with inspiration.

“And as an artist, Carreño belonged to that small, august company of the great, divinely chosen of the world. She was a true aristocrat in every sense among musicians: She knew no envies or frustrations. She was the soul of gallantry. In her eagerness to encourage those who would be called to carry the torch, after it must perforce fall from her hands, as it has done to-day—and in her ardor to give unstinted help to others following after, she always exclaimed, ‘Place aux Jeunes.’ For fifty years she was a glorious accomplishment personified. She played for President Lincoln in the White House and she played this year. She was always conscious of the sacred mission and the calling of the artist, and her devotion to her Art was her religion. It gave her an attitude apart. She had a bell in her heart that rang with beauty, by sheer force of instinct. She was an opal of musicians—all fire and pearl, and she had a contagious alchemy in her soul that· turned every emotion int

o loveliness and rapture.

“As an artist she was a master-woman, full of inspired energy and triumphant, majestic purpose. She was truly a Valkyr among pianists. Above all things, she was an initiated and a consecrated soul. In the face of Carreño’s superb accomplishments, I feel that it would be ungrateful in us to meet here solely to mourn. She has left us all the richer by the inspiration, the example and the high nobility of her life. That part of her can never pass. In the face of what she leaves behind. her in the eternities of Art and in the perfect memories of friendship and of love, it is, I hope, possible to look upon our gathering here as an occasion of solemn joy—a loving farewell to a great woman, a great friend and a great artist, who has done her work well and who has earned her rest—

“‘A little sleep, a little slumber—a little folding of the hands to sleep.’”

After the funeral the body was taken to Union Hill, N. J., for cremation and will be held until after the war for burial in Berlin.

A True American

Mme. Carreño counted herself an American. It is said that when Mme. Carreño was traveling in Europe, she encountered Sarasate, who was heaping abuse upon America. The pianist rallied to America’s defense, saying: “I am a Yankee, if you like. I have lived in the United States almost all my life. It is my country, and no man can say things against it in my presence. It is the greatest country in the world and l love it.”

It was a great tribute to Mme. Carreño’s popularity as a pianist that during the time of war, from Oct. 10, 1915, to April 18, 1916, she filled sixty-five recital and concert engagements in the Central Empires and Scandinavia. The April 18 concert was given in Berlin and one of the most enthusiastic members of the audience was the Crown Princess of Germany. At the end of the concert she sent for Mme. Carreño to come to her box in order to thank her in person for the pleasure that she had derived from her playing.

Suspected as Spy

In an interview with Mme. Carreño published in MUSICAL AMERICA on Sept. 30, 1916, her thrilling experiences of three years in Germany were related. “The great and glorious ‘lioness,’ ‘tigress,’ ‘Valkyrie’ or ‘Brünnhilde’ of the keyboard (take your choice, they all fit),” the writer says, “who came back from three years of Germany last week was held up so often by apprehensive officials, both in belligerent and neutral countries, that she will undoubtedly feel a bit out of her element in being allowed free circulation here.” The pianist tells how she was suspected of being a spy, how she had to produce passports, birth certificates, marriage certificates, at unearthly hours and permitted to go on her way, only after submitting to unheard of indignities.

In this same article Mme. Carreño’s memories of Liszt are given. She played for· the great master only once, but that occasion was indeed memorable. Liszt played for Carreño (she was only twelve years old at the time), and then Carreño played for him. “Let it not seem immodest if I tell that, at the end of my performance, Liszt, who stood in back of me, approached and laid his hands on my head,” said Mme. Carreño. “‘The child will be one of us,’ he said, turning to his friends. For me Liszt’s action was like a benediction.”

Her Principles in Playing

Mme. Carreño’s principles in piano playing, stated last year to a MUSICAL AMERICA writer, are worthy of repetition at this time.

“The great principle in piano playing, relaxation, is what I seek most indefatigably’ to inculcate in my pupils,” said Mme. Carreño. “By relaxation I do not mean flabbiness, or the tendency of some students to flop and swim all over the piano. Relaxation signifies control, and it affects the mentality of the pianist no less than his arms, wrists and fingers. I wish to make my pupils feel that piano playing is easy, not difficult; to make them regard practice as a joy, not a burden; to have them go to the piano as a painter, with a beautiful idea to express, goes to his canvas, takes up his palette and brushes and mixes his colors. But the tension under which so many players labor is dreadful. It is seen even in the muscles of the neck and face. Now this physical distress communicates itself to the intellect, so that the interpretation comes to suffer from strain. When I hear such pianists in recital I instantly feel all the discomfort they are experiencing. My sensations are the same as when I see a cripple hobbling through the street. But too few piano students understand that relaxation is to be achieved by mental process.”

Her Maternal Instinct

Mme. Carreño’s maternal feeling is best described in her own words, when she was commenting upon the numerous letters and messages of affection that she received from her pupils. “That, after all, is the greatest delight in a teacher’s life—or should be—this altogether maternal love which she gives her pupils and to which they respond. I have had no happiness comparable to that of beholding mine turn to me as to a mother. To fathom the student’s soul is the teacher’s highest duty.”

This is Philip Hale’s tribute to Mme. Carreño upon the occasion of her last visit to Boston:

“Mme. Carreño belongs to a Titan race of artists—a race, unfortunately, fast disappearing, to be replaced by youth impertinently eager to rush upon the concert stage, with few lessons learned from the great book of life and in various stages of callowness and crudity. Mme. Carreño, like other artists of her generation, is first of all an interpreter. Her eloquent hands, calm and direct in relation to the keyboard, free from distorting mannerisms in the mysteries of producing tone as in the performance of “intricate technical passages, weave enchanting spells. Broad contact with life has quickened her imagination and stimulated her emotional nature. She has much to say, and she knows the language of tenderness, poetry and passion.”

Memories of MacDowell

One of the last interviews with Mme. Carreño was that given to Hazel Gertrude Kinscella and published in the Dec. 30, 1916, issue of MUSICAL AMERICA. “A Half Century of Piano Playing as Viewed Through Teresa Carreño’s Eyes” was the subject of the article, and in it the famous pianist recalled a multitude of personal experiences. She told of her famous pupil, Edward MacDowell, who was about nine years old when he began to study with her.

At the age of seventeen MacDowell sent to Mme. Carreño a roll of manuscript, accompanied by a letter in which he said: “You know, I have always had absolute confidence in your judgment. Look these over, if you will. If there is anything there any good, I will try some more, but if you think they are of no value, throw them in the paper basket and tell me, and I’ll never write another line.”

“So,” says Mme. Carreño, “I sat down and played them. There were in that bundle, the First Suite, the ‘Hexentanz,’ ‘Erzählen,’ Barcarolle and Etude de Concert. I wrote to MacDowell, ‘Throw no more into the paper basket, but keep on!’”

Mme. Carreño on Some of MacDowell’s Difficulties as Pianist

As a teacher of Edward MacDowell, Mme. Teresa Carreño, the eminent pianist, had some anecdotes to relate of the famous composer. Mme. Carreño said, that as a boy MacDowell was an· example of lack of relaxation. “His forearm was very stiff and I had no end of trouble with him,” said Mme. Carreño in an interview published in the Etude. “I used to sit at the keyboard and illustrate and then say, ‘Now, Eddie, do it just as I did.’ He would reply, ‘I can’t—that’s you—not me.’ However, the example had a good effect upon him and all through his life those who knew him realized how earnestly he worked for relaxed arms and hands.”

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO