100 YEARS AGO...IN MUSICAL AMERICA (92)

100 YEARS AGO...IN MUSICAL AMERICA (92)

May 22, 1915

Page 11

ECHOES OF MUSIC ABROAD

Mary Garden Announces That She Will Make Propaganda for Delius in This Country Next Season—Joseph Holbrooke Breaks Away from the Gloom of His Music Dramas in Opera Ballet He Has Composed for Pavlowa—Prominent English Critic Hopes to See “A New Sense of the Emotional Solidarity of Mankind” in Music After the War—Ysaye Plays at a London Concert—German Language Heard at Budapest Opera Again After Many Years—“Parsifal” Sung in Danish in Copenhagen for First Time—Armand Crabbe Now in Florence

NEXT season Frederick Delius, the much-discussed British composer, is going to have a self-constituted propagandist in this country, and it is none other than Mary Garden that is going to see to it that he is brought to the attention of the American public as he has never been heretofore.

“Delius is a revelation to me,” said the Scottish-American singing actress to a London interviewer the other day. “His works bear the stamp of genius. I am booked up for twenty important concerts in America, and I shall see that the compositions of Delius have a prominent place on my programs. If the British public and those whose business it is to attend to matters musical have not brought Delius into prominence then someone is to blame.”

Miss Garden’s London agents have announced that all her available dates are booked until April, 1916, after which time she may again visit England.

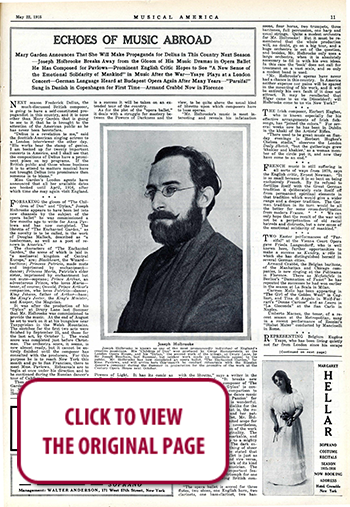

* * * FORSAKING the gloom of “The Children of Don” and “Dylan,” Joseph Holbrooke appears to have been led into new channels by the subject of the opera ballet he was commissioned a few months ago to write for Anna Pavlowa and has now completed. The libretto of “The Enchanted Garden,” as the novelty is to be called, is the work of Douglas Malloch, described as “a lumberman, as well as a poet of renown in America.”

The characters of “The Enchanted Garden,” the scene of which is laid in “a mediaeval kingdom of Central Europe,” are: Blackheart, the Wizard—baritone; Princess Patricia, made mute and imprisoned by enchantment—dancer; Princess Maria, Patricia’s elder sister, imprisoned by enchantment but not mute—soprano; Prince Arthur, an adventurous Prince, who loves Maria—tenor, of course; Oswald, Prince Arthur’s companion, who loves Patricia—dancer; King Johann, father of Arthur—bass; the King’s Jester, the King’s Minister, and Kasper, the Magician.

It was after the production of his “Dylan” at Drury Lane last Summer that Mr. Holbrooke was commissioned to provide the music. At the end of August he set to work on it at his bungalow near Tanygrisian in the Welsh Mountains. The sketches for the first two acts were finished by September 25, and those for the last act, by October 1. The vocal score was completed just before Christmas. The orchestra score, it seems, is now almost ready, but it cannot be entirely finished until the composer has consulted with the producers. For this purpose he is to reach New York this month and go to San Francisco, there to meet Mme. Pavlowa. Rehearsals are to begin at once under his direction and to be continued during the Russian dancer’s tour of California.

Then early in October “The Enchanted Garden” is to have its world première in New York at the Century Opera House, the composer conducting. If it is a success it will be taken on an extended tour of the country.

As for the plot of the “opera ballet,” it deals with a struggle for mastery between the Powers of Darkness and the Powers of Light. It has its comic as well as its tragic moments and may be regarded as a rather heavy type of opera bouffe. The poem is said to be highly suitable for a musical setting, and, judged from a dramatic point of view, to be quite above the usual kind of libretto upon which composers have to base operas.

“Mr. Holbrooke’s music is most interesting and reveals his infatuation with the libretto,” says a writer in the Musical Standard. "It breaks new ground, so far as the composer of ‘The Children of Don’ and ‘Dylan’ is concerned, but bears some comparison to ‘Pierrot and Pierrette.’ The dance music (notably the ‘Dance of Passion’ for Patricia in the last act) is wonderful. Owing to Mme. Pavlowa’s dislike for the modem Russian ballet (that is, the romantic school of dance, and her patronage of the classic ballet, Mr. Holbrooke has had rather a limited scope for dance music, but he has, nevertheless, managed to give this portion of the work a touch of striking originality. The choral writing is also remarkable, and the final chorus worked up to a mighty climax. ‘Joy! Joy! Joy! The dark enchantment vanishes!’ is a thing of sheer beauty. It should here be stated that in the opera ballet the ballet is just as important as the opera and vice versa, and that this is the first work of its kind from the pen of a British musician. The long prelude is another important feature of a work that is a triumph for one of the foremost of living British composers.

“The opera ballet is scored for three flutes, two oboes, one English horn, two clarinets, one bass-clarinet, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three baritones, full percussion, one harp and usual strings. Quite a modest orchestra for Mr. Holbrooke! But it must be remembered that the whole production will, no doubt, go on a big tour, and a huge orchestra is out of the question, and besides, Mr. Holbrooke only uses a large orchestra, when it is absolutely necessary to fill in with his own ideas. In this case the ‘book’ does not call for treatment on a vast scale, and so only a modest band is used.

“Mr. Holbrooke’s operas have never had a chance in this country. In America neither expense nor pains will be spared in the mounting of his work, and it will be entirely his own fault if it does not attract. It may be recollected that Elgar came to us via Düsseldorf; will Holbrooke come to us via New York?”

* * * THE Irish composer, Herbert Hughes, who is known especially for his effective arrangements of Irish folksongs, has “joined the colors.” F or several weeks now he has been in Dublin in the khaki of the Artists’ Rifles.

“There used to be great music on Sunday evenings in Herbert Hughes’s Chelsea studio,” observes the London Daily Sketch, “but the gatherings grew ‘khakier and khakier,’ as a woman member of the circle put it, and now they have come to an end.'”

* * * FRENCH music is still suffering in all sorts of ways from 1870, says the English critic, Ernest Newman. “It is so small because it is so bent on being exclusively French. By its refusal to fertilize itself with the Great German tradition it deliberately cuts itself off from permanent spiritual elements in that tradition which would give a wider range and a deeper tradition. The German tradition in its turn, would be all the better for some cross-fertilization from modern France. We can only hope that the result of the war will not be a perpetuation of old racial hatreds and distrusts, but a new sense of the emotional solidarity of mankind.”

TWO Easter performances of “Parsifal” at the Vienna Court Opera gave Frieda Langendorff, who is well known here, further opportunities to make a success as Kundry, a rôle in which she has distinguished herself in several German cities.

Armand Crabbé, the Belgian baritone, of the Manhattan and Chicago companies, is now singing at the Politeama in Florence. There as Mefistofele in Berlioz’s “Damnation of Faust” he has repeated the successes he had won earlier in the season at La Scala in Milan.

Carmen Melis has been appearing in “The Girl of the Golden West” in Cagliari, and Tina di Angelo in Wolf-Ferrari’s “Donne Curiose” and as Laura in “La Gioconda” at the San Carlo in Naples.

Umberto Macnez, the tenor, of a recent season at the Metropolitan, sang in a recent performance of Rossini’s “Stabat Mater” conducted by Mancinelli in Rome.

* * * REPRESENTING Belgium Eugène Ysaye, who has been living quietly not far from London since his escape from his own country, was one of the soloists at Albert Hall the other day in the Special Series of Sunday Concerts by the Allies. He played the Veracini Sonata in A Minor, the Saint-Saëns Havanaise and numbers by Vieuxtemps and Wagner-Wilhelm.

Jean Vallier, the basso, who spent a season in Oscar Hammerstein’s company at the Manhattan, appeared for France, while William Murdock, pianist, represented Britain.

* * * FOR the first time in many years, and as one of the results of the war that affect musical relations, the German language has been heard once more at the Royal Hungarian Opera in Budapest. The Magyars hitherto have combated energetically and effectually every attempt to infringe upon their national chauvinistic principle that “in the Royal Hungarian Opera only Hungarian should be sung.” The occasion for which this rule was suspended was the guest engagement as Lohengrin of Theodor Kirchner, the new tenor of the Berlin Royal Opera.

* * * THE recent premature death of Alexander Scriabine calls attention to the fact that Russia has been made the poorer by the loss of two of her most gifted creative musicians within the space of eight months. It was in August last that Anatol Liadoff died. Though known to the American public almost exclusively as the composer of two or three grateful pieces of salon music for the pianoforte he was looked up by his countrymen as one of the most illustrious men in their music world. His limited productivity, however—he had scarcely gotten beyond the opus number 70 during the thirty-six years of his creative period—has been the subject of some discussion.

Seeking to find the cause of “this poverty of creative thought,” a Russian writer quoted in the Music Student notes that “the ways of creative genius are past finding out, and it is difficult, therefore, to explain with any certainty the slowness of production which was characteristic of Liadoff. Possibly it was due to his inherent languor and apathy. Rimsky-Korsakoff speaks in his ‘Memoirs’ of Liadoff’s laziness as a lad, and says that he was incapable of compelling himself to do anything. Probably he suffered from this lack of willpower all his life, and this may explain why the ballet on the subject of Remizoff’s ‘Leila and Adelai,’ planned some years ago, remained unfinished.

“Again, Liadoff’s unproductiveness may be connected with the peculiarities of his musical nature, which was extremely sensitive and responsive to anything that was fresh, new, powerful or original, and extraordinarily susceptible to external influences. Not that he lacked originality; on the contrary, most of his compositions have a distinct style of their own, easily recognizable even by those who are not specialists. Nevertheless the development of Liadoff the artist was always dependent on his passionate enthusiasm for this or the other authority. Therein he differed from such men as Scriabine, of the later period, who are able to protect themselves from external influences and to devote all their powers to revealing the potentialities hidden within themselves.

“Liadoff seemed to be stimulated to composition by impressions that came from without. Of course his treatment of those impressions always transformed them into original creations, but he did not manage entirely to conceal the influence of other composers. Thus the pianoforte compositions of his first and longest period are clearly influenced by Schumann and Chopin, and his orchestral pictures by Rimsky-Korsakoff and Wagner. His latest pianoforte works reveal an acquaintance with his great contemporary, Scriabine. But though Liadoff yielded so easily to external influences, he has succeeded in retaining his individuality, by virtue of his great natural talent for composition. At the same time this susceptibility no doubt had a pernicious effect on his output.

“Nor must we forget that Liadoff preferred to work on a small scale, and the miniature demands exceptional efforts from the composer; it is sometimes as difficult to cut a cameo as to carve a monument.”

* * * AN amateur musician who would go neither to concerts nor to opera “because he derived as much pleasure from reading the scores at home as from hearing the music,” must be pronounced a rara avis indeed. Such a one, it seems, was the late Baron de Reuter, who died a tragic death last month. As a young man he began to study music seriously in Paris, according to Musical News, but, becoming dissatisfied with his rate of progress, he returned to London and entered his father’s business, the well-known Reuter’s Agency. Although he devoted himself to this for the rest of his life his love for music remained unabated.

* * * AT a second Red Cross' Benefit Sale of donated manuscripts and other souvenirs of celebrities in London a few days ago an autograph copy of Paderewski’s Minuet brought $40. —J. L. H.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO