100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (383)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (383)

April 23, 1921

Page 3

Einstein, Scientist Supreme, Viewed from the Plane of Music

World’s Master of Physics, Here to Aid Zionist Movement, May Appear Single Time as Violinist for Charitable Cause—Mrs. Einstein Discloses Musical Phases of Her Husband’s Personality—Music His Recreation and Greatest Joy—His Gifts as Improvisor

[Albert Einstein is the propounder of an epochal theory of relativity. A world famous scientific genius, he unites with his specialty a love of and gift for music. He has resolutely barred his door to the press; but MUSICAL AMERICA was privileged to obtain a personal interview with Mrs. Einstein, and is thus enabled to present interesting data concerning the professor’s musical side. Among other distinguished posts, Einstein occupies that of lecturer at the Friedrich Wilhelm University, Berlin, and the University of Leyden, and is a member of many learned bodies and societies. The shock of his great discovery—the principle of relativity—is said to have induced a fourteen-day illness, since he was unable to believe his fornulas had told him the truth. —Editor, MUSICAL AMERICA.]

By Frederick H. Martens

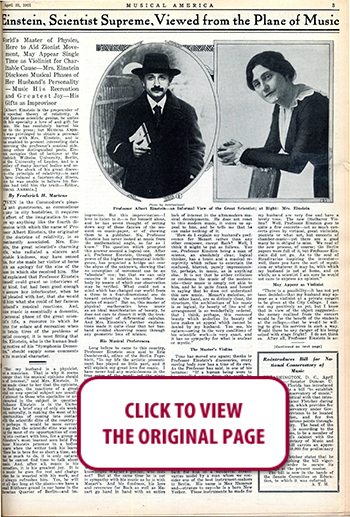

EVEN in the Commodore’s pleasant guestrooms, as commodious as any in city hostelries, it requires an effort of the imagination to conjure up anything like the fourth dimension with which the name of Professor Albert Einstein, the originator of the doctrine of relativity, is so prominently associated. Mrs. Einstein, the great scientist’s charming wife, who radiated a sincere and amiable kindness, may have sensed this, for she made her visitor at home with an apology for the size of the room in which she received him. She had explained that Professor Einstein himself could grant no interviews of any kind, but had been good enough to assure her interlocutor, when he bad pleaded with her, that she would tell him what she could of her famous husband’s musical reactions. And, since music is essentially a domestic, a personal phase of the great scientist’s life, a resource to which he turns for solace and recreation when his brain tires of the problems of spatial concept, it is most fitting that Mrs. Einstein, who is the human leading motive of his “Symphonia Domestica,” should supply some comments on its musical character.

“But my husband is a physicist, not a musician. That is why it seems strange that his musical opinions should be of interest,” said Mrs. Einstein. It was made clear to her that the opinions, the feelings, the reactions of a great mind on any special subject are usually of interest to those who specialize or are interested in the subject in question. Professor Einstein is in the United States for a brief stay of only six weeks and, naturally, is making the most of his opportunities of coming into contact with the scientific elite of the country—or perhaps it would be more correct to say that the scientific élite was making the most of its opportunities of coming into contact with him, for a group of Princeton’s most learned men held Professor Einstein prisoner in a hollow square when the writer took his leave. “Since he is here for so short a time, and has so much to do, it is only natural that he cannot find time to talk about music. And, after all, music is his recreation, it is his greatest joy. It is to music he goes for rest and change when he is wearied with his work, and it always refreshes him. Yes, he will sit all day long at the piano—we have a small Blüthner grand in our home in the Bavarian Quarter of Berlin—and improvise. But this improvisation—I love to listen to it—is for himself alone, and he has never thought of setting down any of these fancies of the moment on music-paper, or of showing them to a publisher. No, Professor Einstein has never looked at music from the mathematical angle, so far as I know.” The question which prompted this answer seemed a logical one. After all, Professor Einstein, through sheer power of the higher mathematical intelligence, has projected a bridge out over the abyss of the unknown, showing that no conception of movement can be an “absolute” one; but that we can only conceive it in relation to some other body by means of which our observation may be verified. What could not a mind which has changed our world from a three to a four-dimensional one do toward extending the scientific boundaries of music? But no, this master of physical mathematics loves music as an ideal manifestation of beauty, he does not care to dissect it with the trenchant scalpel of differential calculus. And Mrs. Einstein’s further explanations made it quite clear that her husband avoided observing music through any geometric lens of science.

His Musical Preferences

Long before he came to this country, Professor Einstein once said to Eric Dombrowski, editor of the Berlin Tageblatt, “In my life the artistic presentiment has played no little part, and it will explain my great love for music. I have never had any music-lessons in the true sense of the word; yet the piano and violin are the most faithful companions of my earthly pilgrimage. In all my intervals of labor I go to them again and again.”

But, as Mrs. Einstein testifies, her husband is not invariably a solitary worshipper at music’s shrine. “My husband has a number of musical friends and, aside from his own individual enjoyment of improvisation at the piano, is a violinist. The violin, in fact, is his instrument rather than the piano. Nothing gives him more pleasure than to unite a few music-lovers and players for a quiet evening’s enjoyment of chamber-music. He is especially fond of the classical quartet literature, of Mozart and Haydn. Mozart rather than Beethoven is his favorite god of music, and of Mozart’s music—his absolute music, in any form—for Professor Einstein does not care for opera—he never tires. Wagner? Naturally, my husband acknowledges Wagner’s genius; who does not? But at the same time he is not in sympathy with his music as he is with Mozart’s. And his fondness, his love and reverence for Bach as well as Mozart go hand in hand with an entire lack of interest in the ultramodern musical developments. He does not react to this modern music, it voices no appeal to him, and he tells me that he can make nothing of it.

‘How do I explain my husband’s preference for Mozart rather than any other composer, except Bach? Well, I think it might be put as follows. You see, Professor Einstein being a man of science, an absolutely clear, logical thinker, has a brain and a musical receptivity which refuse to entertain the confused, blurred, purely impressionistic, perhaps, in music, as in anything else. It is not that he either criticizes or condemns the music of the modernists—their music is simply not akin to him, and he is quite frank and honest in saying that he does not understand this new music. Mozart’s melodies, on the other .hand, are so divinely clear, the structure, the architecture of his music is so logical, its beauty of line and of arrangement is so wonderfully ordered, that I think, perhaps, this reasoned beauty which underlies its beauty of tone makes an appeal which cannot be denied by my husband. You see, his nature—owing to the very conditions of his scientific work—is very exact, and it has no sympathy for what is unclear or mystic.”

The Master’s Violins

Time has moved one apace; thanks to Professor Einstein’s discoveries, every moving body now has a time of its own. As the Professor has said, in one of his lectures: “If a human being were to be propelled away from the earth by means of luminiferous speed to a certain point, and thence shot back again at exactly the same rate of speed, he would not have grown a second older in the interim, even though earthly time might have run on a thousand years while he was underway.” Yet, despite researches which determine the luminiferous rapidity of a body at, say, 300,000 kilometers per second, the violins upon which the man who has rendered obsolete the old geometry we studied at school, plays, are built on the model which Antonius of Cremona perfected from 1700 to 1725. “Yes, my husband has two really fine violins, and one of them he usually carries with him wherever he goes—you know he travels quite a little while in Europe. In Holland, for instance, he has to go from time to time to lecture at the University of Leyden, and he also has lectures to deliver elsewhere. Both his violins were built for him on a wonderful Stradivarius model by a man whom we consider one of the best instrument-makers in Berlin. His name is Max Hummer and—strange to say—he is a born New Yorker. These instruments he made for my husband are very fine and have a lovely tone. The new Ohelhaver Violins? Well, Professor Einstein goes to quite a few concerts—not so much concerts given by virtuosi, great violinists, pianists or what not, but concerts of chamber-music—yet there are a good many he is obliged to miss. We read of the new process, of course; the Berlin papers were full of it, but Professor Einstein did not go. As to the soul of Stradivarius inspiring the inventor—well, there you have the sort of mysticism or whatever it may be, with which my husband is not at home, and on which, as a scientist I am sure he would not care to express an opinion.”

May Appear as Violinist

“There is a possibility—it has not yet been decided—that my husband may appear as a violinist at a private concert to be given at the City College. I cannot say positively as yet, but I know that in view of the object suggested—the money realized from the concert would be for the benefit of the students at the college, —that he would be willing to give his services in such a way. Would there be any danger of his being seized with stage fright? I do not think so. After all, Professor Einstein is accustomed to facing audiences in his lectures, and I do not think he would be at all nervous. His program? I do not know what he would play—perhaps some of the older Italian music; he is very fond of Corelli and Locatelli; or perhaps Bach, and very likely Mozart. After all, he has played with some of our best artists in Berlin, in our musical evenings at home—with Busch and Edwin Fischer. I feel quite certain that you would never hear him play a Wagner transcription, because to his thinking his music is too theatrical.” There is no gainsaying the fact that were Professor Einstein to play a violin recital in New York, it could not help but be an occasion of unique interest. One might compare it to Copernicus consenting, shortly after the appearance of his epoch-making treatise, the De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, to give a lute concert in the diocese of Ermeland; or to Galileo agreeing to play an organ recital at Florence after his Dialogo dei due massimi sistemi del mondo had come from the Landini presses in that city in 1632. Yet both Professor Einstein’s great scientific predecessors were men who never turned a deaf ear to a deserving appeal; and the man who, in the course of a few decades has evoked on a basis of scientific investigation, a world panorama, whose grandeur almost exceeds human comprehension, is deserving of all respect if he consents, in a worthy cause, to show for once that he is an artist-philanthropist as well as a physicist. It is to be hoped, since Professor Einstein—as well he may, in view of the continuous demands on his time—cannot himself very well give his musical reactions viva voce, that he will consent to “say it with tones” at the projected concert.

New York Has Other Rhythms Than Berlin

“You ask me how I like it here?” Yes, the old, old question had been put once more. It is always a temptation, when one is addressing it to an active, keen intelligence. Nor did Mrs. Einstein’s answer prove a disappointment. “You have other rhythms here than in Berlin. And the wild, ceaseless ebb and flow of your crowds. . . .” At this juncture there was a knock at the door and a visitor was announced. He who reads should know how to run. Mrs. Einstein had been so genuinely kind and amiable that a courteous acquiescence in the inevitable seemed the only right and proper course. With hosts of stillborn questions rising to his lips the writer withdrew. As he went he could see Professor Einstein, his gray hair billowing about his high brow, his intelligent, reflective eyes ruminating some point just advanced, standing like a planetary body among a group of scientific satellites. What were the learned men discussing? Some delicate, subtle detail of relativistic positivism? The curvature of rectilinear light-rays? The specific mathematical expression in formulae of the new dimensional radius? Certainly not music.

But the fact that the wife of a great scientist had found time, despite the thousand and one demands upon her attention, to give some details anent the musical side of her husband’s personality, is not without a meaning of its own. It reflects, in a manner, the scientist’s willingness to give of his knowledge to those who ask. He himself may not grasp why he, who is a prophet of the higher mathematics, should be asked to express himself with regard to an art which is his recreation. But, knowing that he was asked in all sincerity (the mere fact that a man of Einstein’s pre-eminent attainment in another field holds music in such esteem honors the art), and it being impossible for him to speak for himself, he was kind enough to select for his mouthpiece Mrs. Einstein, who knows his views, his feelings, his reactions, and could express them with authority. The compliment implied for MUSICAL AMERICA readers is a delicate one, and one which they have every reason to appreciate.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO