100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (140)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (140)

April 22, 1916

Page 51

NIJINSKY’S ADVENT ACCOMPLISHED WITH DUE ECLAT

“Caruso of the Ballet” Attracts Large Audiences to the Metropolitan and Awakens Considerable Enthusiasm—An Amazing Display of Agility—“Thamar,” in Its Initial New York Performance, Proves Chiefly Remarkable for Its Colorful Bakst Pictures

BUSINESS of high importance was transacted by Diaghileff’s dancers both afternoon and evening at the Metropolitan Opera House on ·Wednesday of last week. At the matinée the largest and ·most expectant audience attracted by the ballet up to date turned out to see Nijinsky, who, having disposed of sordid financial issues with results satisfactory to his exalted artistic dignity, allowed lovers of the dance to behold the operation of his fabled greatness. Now the primary complaint levied against the ballet since its first appearance in America has been the lack of stars of the first magnitude. Nijinsky at last supplies that deficiency. He is the Caruso of the company, if you will, the idol to be worshipped by a public which desires to concentrate its affections on an individual, not feed them piecemeal to an ensemble, however deserving. Thursday afternoon’s gathering reveled in the joy of acclaiming a personality and the auditorium reverberated with sounds and vibrated with emotions that have not disturbed its atmosphere since Caruso went away three weeks ago.

Nijinsky appeared first in the “Spectre of the Rose,” later in the title part of “Petrouchka.” A burst of applause followed his bound through the open window in the visualized version of the “Invitation to the Dance,” and gasps accompanied some of his following evolutions. And when the piece ended and he appeared before the curtain an ovation of which Caruso might have been proud was his reward. He came out fifteen times, to be exact, and in addition to sounds of gladness got flowers and wreaths.

Nijinsky is unquestionably an amazing dancer. He is said to have been nervous last week, partly because of the naturally disquieting effect of a début, partly because he had not danced in a long time. Later performances will, therefore, probably present him in a mere favorable light. But he revealed in his first dance his great technical facility, the agility of a deer, an exceptionally subtle rhythmic sense, great vitality and suave bodily grace. His far-reaching leaps as he entered the window and circled about the room and his volant exit were calculated to stir even the phlegmatic. The rest of the dance impressed one somewhat less and at moments Mr. Nijinsky seemed a trifle heavy—a condition conceivably due to temporary causes. Yet, if possibly a shade more airy of motion than the warmly remembered Michael Mordkin, it may be questioned whether he will exert so lasting an effect, wanting as he does the bold virility of the latter. ·Except for his legs, which are ·as palpably muscular as those of an athlete, Nijinsky’s appearance, bearing and manner disturb by a most unprepossessing effeminacy—an element as forcibly apparent in the airs and graces with which he acknowledged the favor of the audience as in his evolutions.

In “Petrouchka”

In “Petrouchka” Nijinsky executed some of the business of the part differently from his predecessor, Mr. Massin, but without any perceptible improvement in consequence. Indeed, he lacked the mechanical rigidity of gesture and motion whereby Mr. Massin so perfectly carries out the marionette illusion. And the whole impersonation fell in its way below the artistic level attained by Mr. Bolm as the Moor.

The other works given at the matinée were “Scheherazade” and “Prince Igor.” The scheduled order had to be reversed on account of the accident which befell Flora Revalles just before the performance began. Opening a letter handed to her in her dressing room she received in her eyes a cloud of powder and straightway fainted. Coming to she insisted that the stuff was poison sent, most probably, by a German spy. “In Russia,” she declared, “there is a method of poisoning persons in that way. I thought surely it was some kind of black-hand letter when I read that this man, whom I do not know of, was related to a German prince. Anyway, I’m glad I didn’t breathe any of the powder or I’m sure I’d be quite dead by now.” The man referred to was one “Prince A. A. von Zeil,” who sent a note with the powder to the effect that he was descended from Napoleon and that his family tree had borne such fruit as the wife of Peter the Great, a certain German Prince Maximilian von Zeil and a contemporary chief of police in Philadelphia.

Another theory, however, was advanced by the friends of Nijinsky, who hinted darkly that the whole affair was engineered by the dancer to detract attention from the debutant.

First Performance of “Thamar”

In the evening took place the initial New York performance of “Thamar.” Boston got the first American view of it about two months ago and liked it. Last week’s audience took it politely, but declined to lose its head over it. Pictorially the piece is without question the most gorgeous thing Diaghileff’s people have thus far exhibited; but the plot and music scarcely suffice to raise a ripple of interest. However, it barely plays over fifteen minutes, so there is no danger of boredom, particularly as the eye feasts on Bakst in the very fullness of his colorful splendor. In nothing else has he attained such ideal correspondence of scenic character and order of attire. The color scheme is deep, dark red, relieved with green and old gold, and the forms, proportions and perspectives stir the imagination like visions out of the Arabian Nights. The abode of Thamar·, Queen of “Georgia” (there is really such a place somewhere in the Caucasus), is a sort of funnel-shaped chamber of stupendous height (the sense of altitude being marvelously conveyed), walled with great red tiles, both square and round, save at the rear, where a great gray-green panel rises up, slashed with one broad, zigzagging streak of gold. A curtained portal at the right gives views of snow-covered peaks, while in a remote corner a secret door opens upon a foaming cataract. On a couch by the wide entrance reclines Thamar in the posture of Amneris and waving a scarf at some unseen individual in the distance, like Isolde. A knight comes in and is received amorously. He is given to drink, after which he dances madly, sometimes with Thamar and sometimes alone, while the queen’s guards and female attendants and slaves rush, whirl and eddy in labyrinthine mazes. Then for no apparent reason the knight is stabbed to death by Thamar·and his remains are unceremoniously consigned to the convenient waterfall in back. Thamar returns to her couch and agitates her scarf in invitation to her next would-be lover and dancing partner.

All of which is not unlike “Cleopatra,” though far from as gripping, and the incessant evolutions of the ensemble detract attention from the two principals and the dramatic idea of the piece. Moreover, it seemed so largely pointless last week that a surmise to the effect that the love-making had been meticulously expurgated would not down. The music that does service for the affair is Balakireff's symphonic poem, after Lermontov. It was played here in its original state some years ago by the Russian Symphony Orchestra and without creating any impression. It seemed .as uninteresting last week. Fairly well scored, it is devoid of melodic or dramatic ideas. The best that can be said of it is that it never detracts the attention from the stage pictures or action.

A Stronger Impression

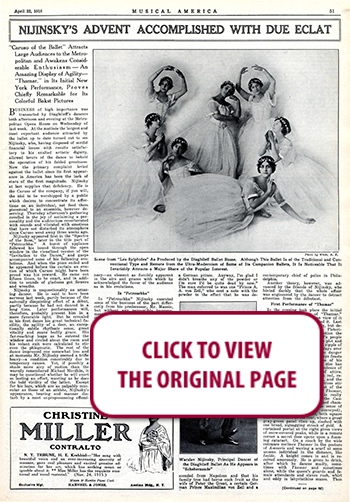

Nijinsky appeared again on Friday and Saturday nights. Laboring under no such stress of nervousness as the previous Wednesday, he created a correspondingly greater impression and the audiences, which grew magically in size, fell into the very ecstasy of enthusiasm. For a time the depression and melancholy which have sat enthroned at the Metropolitan since the ballet took up its abode there were dispelled. On Friday night the star of the company appeared in “Sylphides” and “Carnival.” All the best qualities of his dancing at his début—the amazing rhythm, the ethereal suppleness, the airy grace and floating motion—were noted once more, though not without that effeminacy of manner mentioned above. But the pictorial features of the “Sylphides” were noticeably improved through Nijinsky’s skill as a stage manager.

This skill benefited “Scheherazade” on Saturday night, which showed evidences of restudy. In this Nijinsky appeared as the Moorish slave and caught the huge· audience by his wild abandon and impassioned action. His death scene was particularly remarkable. But the audience took even greater delight in the “Princess Enchantée” disclosed on Saturday night for the first time at the Metropolitan. In that his dancing took on a superlative character. As one spectator observed, “he seemed not to touch the stage more than ten times during the whole ballet.” The other works seen were the “Fire Bird” and “Prince Igor.”

Changes in the bills were made necessary on Thursday night because of an injury to his knee sustained by Mr. Bolm. This eliminated the scheduled repetition of “Thamar,” and substituted for it “Sylphides” and “Prince Igor.” The “Fire Bird” and “Soleil de Nuit” completed the bill. On Saturday afternoon a moderate audience saw “Petrouchka,” “Sylphides,” “Igor” and “Soleil de Nuit.” Last Monday evening Nijinsky danced again in the “Spectre de la Rose” and “Carnival.” The scheduled novelty for the third week was “Narcisse,” billed for Thursday night. —H. F. P.

Other critical comments on Nijinsky’s American début:

Mr. Nijinsky’s début was a success, though he scarcely provided the sensational features that this public had been led to expect of him. —The Times.

Mr. Nijinsky showed himself a stage artist of refinement, taste, direct method and conviction. —The Sun.

Mr. Nijinsky is a male dancer such as New York has not seen in this generation and, perhaps, in any. He lacks the virility of Mikael Mordkin, but as a dancer pure and simple, as an interpretative artist, as an original personality, he stands alone. —The Tribune.

See Nijinsky as Petrouchka and you will never forget the experience. The more you dwell on his portrayal the more it will haunt you. —The Press.

That Mr. Nijinsky is effeminate at times is obvious. But quite apart from that he is a great artist, probably the greatest whom the present generation has seen here. —The Herald.

He dances with a bodily rhythm no man has ever shown Americans, and every movement of head, limbs and torso, as well as his facial expressiveness, has a meaning that is well-nigh perfect. —The World.

While the effeminate quality, almost inseparable from the male ballet dancer, is quite visible in Nijinsky, he has at the same time a certain masculinity of strength and rhythm which counteracts the other impression. —The Evening Post.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO