100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (236)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (236)

April 13, 1918

Page 5

DEBUSSY THE MAN, AS MAGGIE TEYTE KNEW HIM

English Soprano Describes Late Composer as “Primitive, Self-Centered and Relentless,” Whose Creative Genius for Music Was a Thing Apart from His Personal Life—Anecdotes That Were Typical of the Frenchman’s Philosophy—Hated to Hear His Own Music Performed

By MAY STANLEY

ONE might count on the fingers of one hand the persons who have been admitted to the inner circle of the life of Claude Debussy, the famous French composer, whose passing removes an absolutely unique figure from the world of art. One of this little group is Maggie Teyte, the gifted English soprano, who had the rare privilege of not only preparing her Mélisande for the Paris presentation of Debussy’s “Pelléas and Mélisande” under the personal direction of the eminent composer of the opera, but who also worked with Debussy on the programs of his songs which she has presented in recital in France, England and America.

Interviewing Miss Teyte these days is rather a difficult matter, as the singer’s engagements for the spring season are treading on one another’s heels, but I managed to get a half hour’s chat with her sandwiched in between an afternoon concert she had been attending and the train that was taking her to Wheeling for a recital.

“To describe one’s impressions of Debussy is a difficult matter,” the singer replied thoughtfully, when the question was asked. “His was such an unusual personality. With most geniuses their work, their dreams, color the rest of their lives. It was not so with him. It was as if someone had taken a bit of genius, put it in a box and thrown it violently at his head. It stuck, yes, but it was not a part of him, of his everyday life, his modes of thought. You see what I mean?

“In his personal life, his methods of dealing with the problems of life, Debussy was primitive, self-centered and as relentless and pitiless as life itself. His music, on the other hand, is the essence of exotic refinement. He gathers up all the color of modern life under his hand, as if it were the strings of a piano. Sometimes he thumps and sometimes he plays delicate arpeggios, but always it is the discord on the subtle harmonies of modernity—never that of the primitive, the barbaric.

Hated to Hear His Music

“He was the most taciturn man I have ever met, and the most nervous. The one thing that he hated above all others was to hear someone else play his music. I recall one evening at a concert of his works in Paris that the first violinist came off the stage in high spirits after the playing of Debussy’s Quartet. ‘Was it not fine, was it not beautifully played?’ he demanded of the people standing ‘back stage.’ Debussy overheard him and withered the unfortunate man with a look. ‘You played like pigs,’ he said scornfully, and strode away, leaving the hapless player covered with shame and confusion. I have never in my life felt so sorry for anyone as I did for my accompanist who went with me for the dress rehearsal of a recital which I was to give of Debussy songs. He always insisted on this—a rehearsal with accompanist of the program just as it was to be given. My accompanist stood in mortal dread of Debussy’s anger, knowing his active dislike for listening to his music done by other people. Once during the program he held a note a bit too long; it was not enough to call a mistake, but I saw the man actually turn red, then deathly white, every ·bit of color left his face in sheer dismay. It was one of the most dramatic incidents of my life and left an indelible impression on my mind.

“I have said that Debussy was taciturn. A typical illustration is the reception he gave me when I first went to him to study the music of ‘Pelléas and Mélisande.’ He was sitting in a room adjoining his study and listened to me sing some of the music before coming into the room. I was very young at the time, and he appeared surprised at my youthful appearance and seemed to doubt that I was the singer he had heard at the Opéra Comique.

“He came into the room where I was and abruptly seated himself at the piano. ‘Are you Mlle. Teyte?’ he asked suddenly. ‘Qui, Monsieur,’ I replied. ‘Mlle. Maggie Teyte of the Opéra Comique?’ he persisted. ‘Oui, Monsieur,’ I again answered. ‘Très bien,’ he said, and turned to the music. There were days in our work together when he would come in, plunge into the score and never exchange a word beyond a slight comment on the score here and there.

A Supreme Teacher

“If Debussy had not had the creative gift I think he would have been one of the most inspired teachers that the world has known. He had almost supernatural gifts of making one see with his eyes, think his thoughts, about the work. But the creative power came in to distract him, and so a great teacher was lost.” Miss Teyte describes Debussy as “one of the most dynamic men imaginable.” He surcharged the atmosphere of a room when he entered it with his nervous force.

“He had a most noticeable way of breathing, a sort of whistling.” she says. ‘I do not know if it was caused by heart trouble or simply nerves, but the effect was to key one up; one was always conscious of that powerful, nervous force at work, directing and controlling. With all his nervousness and irritability he was most fair-minded and open to conviction. Once, I recall, I sang a passage slightly different from the way in which it was indicated. He looked up quickly, thought a moment, and then said, ‘You are right, quite right; that is the way you should sing it,’ and passed on·without further comment.

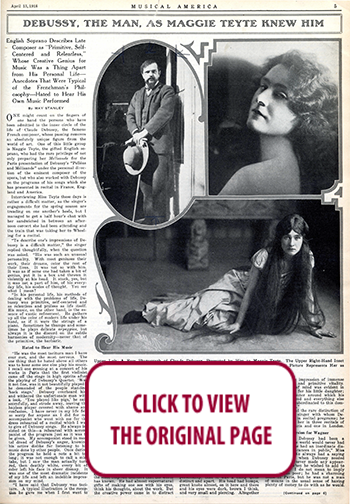

“If you look at Debussy’s portrait you will see at once what I mean when I say that his genius did not permeate his personality, that it was a thing quite distinct and apart. His head had bumps, great knobs almost, on it here and there and his eyes were dark, brown I think, and very small and piercing. Altogether he gave one the impression of immense physical power and primitive vitality. His singleness of mind was evident in the love he had for his little daughter; she was the center around which his affections revolved and everything else in his life was subordinated to this dominating emotion.”

Miss Teyte had the rare distinction of being the only singer with · whom Debussy appeared in recital programs; he was heard with her in three recitals of his songs in Paris and one in London.

His Aversion for Wagner

“I think if Debussy had been a wealthy man the world would never had heard him, as he had an inordinate distaste for appearances in public,” Miss Teyte says. “We always had a saying that we knew when Debussy needed money, for he never made any appearances except when he wished to add to his finances. I do not mean to imply that he was poor; he had a charming home in Paris, but he was not a man of means in the usual sense of having plenty of money to do with as he would.

“One of his idiosyncrasies was his great dislike for having his picture taken; he could not endure the thought and I was very proud indeed when he posed once for a picture for me at my earnest request.

“I think that one of the great mistakes of the modern school of composition has been its tendency to copy Debussy. His work was not the kind on which a school can be founded; it stands out distinctly, a thing apart; it is perfectly groomed even in its discords, but his imitators have achieved only discordant untidiness. That is the reason why I do not believe that there is anything permanent in the art of the modern school, because each example stands out complete in itself as a finished thing, not something on which succeeding generations can build.

“Did you know that Debussy hated Wagner vehemently? To me that was another of his contradictions—that he should so hate Wagner and so admire Mozart. He had a theory that just when Wagner got a lot of lovely jewels of thought together and was about to transmute them into music something came along and joggled his elbow—and Debussy didn’t care for people who allowed their elbows to be joggled.”

And just then the taxi came for Miss Teyte and I had to say goodbye, with a mental reservation that someday I was going to have a much longer chat, when the brilliant little songbird had time to talk about herself.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO