100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (276)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (276)

March 29, 1919

Page 1

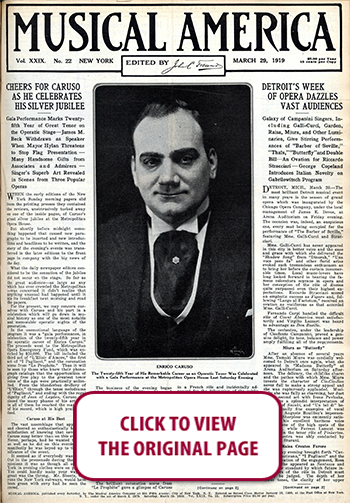

CHEERS FOR CARUSO AS HE CELEBRATES HIS SILVER JUBILEE

Gala Performance Marks Twenty-fifth Year of Great Tenor on the Operatic Stage—James M. Beck Withdraws as Speaker When Mayor Hylan Threatens to Stop Flag Presentation—Many Handsome Gifts from Associates and Admirers—Singer’s Superb Art Revealed in Scenes from Three Popular Operas

WHEN the early editions of the New York Sunday morning papers slid from the printing presses they contained the reviews, unobtrusively tucked away on one of the inside pages, of Caruso’s great silver jubilee at the Metropolitan Opera House.

But shortly before midnight something happened that caused new paragraphs to be inserted and new introductions and headlines to be written, and the story of the evening’s events was transferred in the later editions to the front page in company with the big news of the day.

What the daily newspaper editors considered to be the sensation of the jubilee did not occur on the stage. So far as the great audience—as large as any which has ever crowded the Metropolitan—was concerned it didn’t realize that anything unusual had happened until it ate its breakfast next morning and read the papers.

For the present, we may concern ourselves with Caruso and his part in a celebration which will go down in musical history as one of the most notable and memorable operatic nights of the generation.

In the unemotional language of the program it was a “gala performance, in celebration of the twenty-fifth year in the operatic career of Enrico Caruso.” The proceeds went to the Metropolitan Opera Emergency Fund, which was enriched by $25,000. The bill included the third act of “L’Elisir d’Amore,” the first act of “I Pagliacci,” and the coronation scene from “Le Prophète.” Thus it will be seen by those who know their phonograph catalogs that the opportunities of giving free play to the greatest tenor voice of the age were practically unlimited. From the blunderbus drollery of “L’Elisir,” through the tense melodrama of “Pagliacci,” and ending with the regal dignity of Jean of Leyden, Caruso disclosed the many phases of his art, and in all of them he reached the maximum of his record, which is high praise, indeed.

Caruso at His Best

The vast assemblage that applauded and cheered so enthusiastically had the satisfaction of knowing that never had Caruso sung better than on this evening. Never, perhaps, had he wanted to sing as well as he did on this evening, for manifestly he was keyed up to the significance of the event.

It seemed as if everybody was there. Out in the promenade during the intermissions it was as though all of New York in evening clothes were on parade. You could hardly make your way, so great was the throng. Mr. Shonts, who runs the New York subways, would have been green with envy had he seen the crowd.

The business of the evening began with the third act of “L’Elisir d’Amore,” with Barrientos, Lenora Sparkes, Scotti and Didur as the other members of the cast and with Papi in the conductor’s box. In the opening bars of the famous “Una furtiva lagrima” aria we are certain chills ran down the backs of the hearers as a reaction to the sheer loveliness of tone which issued from the golden throat. It was an exhibition of pure bel canto that will remain long in memories that harbor many another conspicuous artistic experience.

We have always suspected that Caruso likes best to sing Canio. Certainly on this occasion he put his whole soul into the part and his famous sob aria electrified the audience. In the cast with him were Claudia Muzio, a wholly charming Nedda; de Luca as Tanio, Bada as Beppo and Reinald Werrenrath, making his second operatic appearance as Silvio. Moranzoni conducted.

The ·brilliant coronation scene from “Le Prophète” gave a glimpse of Caruso in a French rôle and incidentally advanced for the delectation of the public some of the finest singing that Margaret Matzenauer has done this season. Her Fides becomes a memorable addition to the operatic portraits in New York’s musical galleries. Bodansky conducted.

When the Audience Warmed Up

Until the close of the tear aria in “L’Elisir” the audience was most respectable. It had apparently decided not to split its kid gloves. But the glorious voice and the great climax broke the chill. Pandemonium was loose and during the remainder of the evening there was ovation after ovation.

After the last curtain call and following the performance of Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance,” conducted spiritedly by Richard Hageman, there was a twenty-minute wait, during which politics and music came into close contact though not in public view. James M. Beck, who had been invited to make an address, was the subject of the controversy. Mayor John F. Hylan, who was present in his official capacity, in connection with the proposed presentation by the city to Caruso, of the city flag, to commemorate the tenor’s service in the cause of municipal music, sent his secretary, Grover Whalen, to see Otto H. Kahn and demand the withdrawal of Mr. Beck from the program. The official message bore the threat that if Mr. Beck whose recent criticism of President Wilson’s foreign policies placed him beyond the good graces of the Democratic party, were permitted to make his address the Mayor and his official family would leave the auditorium and there would be no flag presentation to cap the climax of the evening.

Mr. Beck, when informed of the Mayor’s ultimatum, told those who had charge of the celebration that he had no intention of interfering with the honors planned for Mr. Caruso and accordingly would withdraw from the program.

The Presentation Ceremony

When the political contretemps had been settled the big curtain separated, revealing an interior setting with the Metropolitan staff, members of the company, board of directors and others seated about a big table bearing many gifts for the tenor. Mr. Kahn was the first speaker. He said:

“When offering you the tribute of our admiration, it is not the glory of your voice which I have in mind primarily, though it is the most glorious and perfect voice of a generation, for having heard which posterity will envy us.

“One can admire a voice without admiring the man. But in your case we admire the voice, the art and the man. I have in mind your high and artistic striving, your serious artistic purpose, your artist’s conscience, which makes you put forth on every occasion the very best you are capable of giving, and your fine sense of the dignity .and duty and responsibility which attach to your great name and your unique position.

“I have in mind your boundless generosity, your modesty, kindliness and simplicity, your unfailing consideration for others.

“Bearing a name which has become a household word throughout the world, being sought and courted and fêted by the great ones of the earth in all lands you have retained the plain human qualities of a man and a gentleman, which have won you the affection of those whose privilege it is to know you personally.

His Loyalty to America

“I have in mind your fine loyalty to the country and to this city. A son of the noble country which has taken so vital and glorious a part in the war now so happily concluded; a son of the great nation with whom we were linked by close and whole-hearted comradeship in peace, you have given abundant proof again and again of your warm attachment to America and to New York. You have managed even to find a generous thought, a pleasant gesture and a generous word in going through the painful process of paying an income tax running into six figures.”

Then Mr. Kahn introduced Police Commissioner Enright, who made a brief speech, presenting Caruso with the flag of the City of New York in recognition of his aid in the cause of municipal music. Through the efforts of City Chamberlain Philip Berolzheimer, also present on this occasion, the tenor had taken part in Mayor Hylan’s Peoples’ Concerts last summer, and the presentation marked the appreciation of the municipal government for his services.

Mme. Farrar as Cheer Leader

When Caruso arose to respond the house rose to him. There was a tremendous ovation, during which the irrepressible Geraldine Farrar jumped from her seat on the stage and made a flying leap for the singer, deftly planting a kiss upon his blushing cheek. Mme. Farrar led in three cheers for Caruso and Caruso led in three cheers for America.

When quiet was restored the tenor made a speech, probably the longest speech in English he has ever made in his life. He said:

Caruso’s Speech

“My heart is beating so hard with the emotion that I feel that I am afraid I cannot even put a few words together. I am sure you will forgive me if I do not make a long speech. I can only thank you and beg you to accept my sincerest and most heartfelt gratitude for to-night and for all the very many kindnesses which you have showered upon me. I assure you that I will never forget this occasion and ever cherish in my heart of hearts my affection for my dear American friends. Thank you! Thank you! Thank you!”

The gifts to the tenor included a gold medal from the Metropolitan management, and another from the chiefs of departments on the stage; an 18-in. silver loving-cup from the chorus, and from the orchestra men an ornate silver vase, as well as a great Italian vase of silver, 2 ft. high, from the Opera Directors’ Board, and a silver fruit dish from the directors of the Victor Talking Machine Company.

His fellow artists gave Caruso a platinum watch, having seventy-eight little diamonds set around the rim and ornamented on the back with 140 small stones in three circles about the monogram “E. C.,” made up of sixty-one square-cut sapphires. It was presented in a silver box on which were engraved the names of all the members of the Metropolitan’s company of singing stars.

From the Metropolitan Opera and Real Estate Company stockholders, the owners of the theater, there was an illuminated parchment signed on behalf of all the thirty-five families holding boxes in the $7,000,000 Golden Horseshoe by their president, A. D. Juilliard. An engrossed parchment from the Philadelphia Opera directors was signed by Edward T. Stotesbury as president, and an illuminated scroll from the Brooklyn Academy directors by President Thomas L. Leeming.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO