100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (130)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (130)

February 12, 1916

Page 3

TECHNIQUE, NOT BRAINS, PIANISTS’ CHIEF ASSET

Such Is the Dictum of Martinus Sieveking, Who Further Declares That Building a Technique Is Merely a Matter of Physical Culture—Dutch Pianist Has Special Keyboard Constructed to Fit His Broad Fingers—At His Recitals His Chair Is Placed at Spot Measured Off by Him—Same Shoes for Concerts as for Practicing

BUILDING a perfect piano technique is only a question of physical culture, says Martinus Sieveking, the noted Dutch pianist who arrived in New York recently from Paris, and who will be heard here in recital later in the season.

Ten years ago Mr. Sieveking gave up composition, concertizing and pedagogy, cut himself off from all outside interests, and devoted his life to evolving a method whereby an absolutely perfect piano technique could be mastered in a comparatively limited space of time.

Secrets of Tone Production

“You want to know about my method? Very good, I tell you. Sit down here. No, that is not near enough the piano for you.” Mr. Sieveking adjusted the chair before the piano, picked up my arm, dropped it. Then—“Relax,” he said. “Let all your arm relax—so; that is better. Higher, now! There, you see that you have no control over your hands and arms, yet you have learned to play. Well, well, so it is with many people who are playing in public; they have not learned the secrets of dead weight, and dead weight of the arm increases the volume of tone 100 per cent.

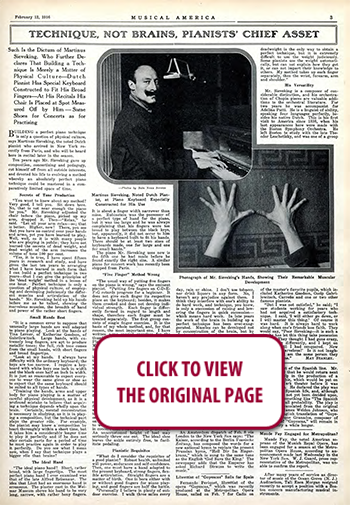

“Yes, it is true, I have spent fifteen years in research and study, and have given the last ten years to arranging what I have learned in such form that I can build a perfect technique in two years-that I can give the principles of the 'dead weight' method in a lesson of one hour. Perfect technique is only a question of physical culture, of employing and deve-loping judiciously the different muscles and articulation of the hands.” Mr. Sieveking held up his hands before me as he talked, showing the marvelous mus~les, the breadth of hand and power of the rather short fingers.

Small Hands Best

“It is a common error to suppose that unusually large hands are well adapted to piano playing. ·Look at the hands of Tina Lerner, of Katherine Goodson, of Gabrilowitsch. Large hands, with extremely long fingers, are apt to produce metallic tones; the full, rich tone comes from the small hands, with short fingers and broad fingertips.

“Look at my hands. I always have difficulty with the ordinary keyboard; the keys are too narrow. I require a keyboard with white keys one inch in width and the black ones half an inch in width. It is just as reasonable to expect everyone to wear the same glove or shoe as to expect that the same keyboard should be suited to all types of hands.

“Training the hands, arms and upper body for piano playing is a matter of careful physical development, as it is a profound mistake to believe that acquiring a technique depends wholly upon the brain. Certainly, mental concentration is necessary in studying, as it is in playing a composition, but the technical part plays the greater role. For example, the pianist may know a ' composition by heart thoroughly within a short time, but it takes him a considerably longer time to play it perfectly and if he does not play certain parts for a period of time he must practice again in order to play it perfectly. Do you see what I mean now, when I say that technique plays a bigger role than brains?

The Ideal Hand

“The ideal piano hand? Short, rather broad, with large fingertips. The most perfect piano hand I ever examined was that of the late Alfred Reisenaur. The idea that Liszt had an enormous hand is erroneous. The plaster cast in the Weimar Museum shows his hand to be very long, narrow, with rather bony fingers. It is about a finger width narrower than mine. Rubinstein was the possessor of a perfect type of hand for the piano, but it was too large and he was always complaining that his fingers were too broad to play between the black keys, but, apparently, it did not occur to him to have a keyboard built to fit his hands. There should be at least two sizes of keyboards made, one for large and one for small hands.”

The piano Mr. Sieveking uses now is the fifth one he had made before he found exactly the right size. A similar piano for concert work has recently been shipped from Paris.

“Five Finger” Method Wrong

“The usual way of putting five fingers on the piano is wrong,” says the eminent pianist. “Putting five fingers on C-D-E-F- G retards progress for a beginner. It does not give each finger its respective place on the keyboard; besides, it makes them crooked and does not develop individual strength. Each finger is differently formed in regard to length and shape, therefore each finger must be treated separately. The first group consists of single finger exercise. It is the basis of my whole method, and, for that reason, the most important one. I have written some special exercises for the thumb preparatory to scale playing. Playing a perfect scale—especially in C Major—is one of the hardest problems in piano technique.

“The seat and the position at the piano is of the greatest importance, a thing that many pianists do not realize. Personally I always use the same chair. It took me several years to find the proper position. After much experimenting I found the most satisfactory seat to be low and rather close to the keyboard. A high seat makes rapid wrist work and octaves in quick succession rather tiresome, and the tone produced is not so good.

“Have you seen famous pianists move their chairs about and adjust them before starting a concert program? I measure the distance from the keyboard to the back of the chair, mark the place on the floor and have the chair placed on the indicated spot. Then I am careful to wear the same shoes when appearing in concert that I have used in practicing. An unaccustomed height of heel may seriously throw one out. The ideal shoe leaves the ankle entirely free, to facilitate pedaling.

Pianistic Requisites

“What do I consider the requisites of a good pianist? Robust health, unlimited will power, endurance and self-confidence. Then, one must have a hand adapted to the present keyboard, strong fingers, flexible articulation. Straight fingers are a matter of birth. One is born either with or without good fingers for piano playing, and good fingers are half the battle. “Personally I believe in plenty of outdoor exercise. I walk three miles every day, rain or shine. I don't use tobacco, nor drink liquors in any form. No, I haven't any prejudice against them. I think they interfere with one's ability to do hard work, and technique, you know, is only a succession of raising and lowering the fingers in quick succession—which means hard work. In late years the work of the brain in building up a perfect technique has been over-exaggerated. Muscles can be developed not by concentration of the brain, but by playing, thousands of times, some sets of exercises. Technique is a thing quite apart from phrasing, memorizing, dynamics, and all that, and must be developed first.

“I came to the conclusion about ten years ago that the constant use of the deadweight is the only way to obtain a perfect technique, but it is extremely difficult to use the weight judiciously. Some pianists use the weight automatically, but cannot explain how they got it, or cannot impart their knowledge to others. My method takes up each finger separately, then the wrist, forearm, arm and shoulder.”

His Versatility

Mr. Sieveking is a composer of considerable distinction, and his orchestration of Chopin pieces are valuable additions to the orchestral literature. For two years he was accompanist for Adelina Patti. He is a linguist of ability, speaking four languages perfectly, besides his native Dutch. This is his first visit to America since 1898, when his last appearances here were made with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He left Boston to study with the late Theodor Leschetizky, and was one of a group of the master's favorite pupils, which included Katherine Goodson, Ossip Gabrilowitsch, Carreño and one or two other famous pianists.

“But I was not satisfied,” he said; “I saw students working for years who had not acquired a satisfactory technique. I said, ‘I will either go down, or ·I will master this thing.’ Of course it was hard. It is always hard to work along when one's friends lose faith. They would say, “Poor Sieveking—it is such a pity he has let this thing take possession of him.’ They thought I had gone crazy, but I knew differently, and I kept on working until I had conquered. Now they say, ‘Marvelous!’ Is it not laughable? For I am the same person they thought insane.” —MAY STANLEY.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO