100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (124)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (124)

December 25, 1915

Page 3

GRANADOS HERE FOR PRODUCTION OF “GOYESCAS”

Composer Anxious to Spread a Knowledge of Spanish Music in America as Well as to Superintend the Preparation of His Opera at the Metropolitan—Real Spanish National Music Unknown Here, He Declares—The Genesis and History of “Goyescas”—Operatic Convention Ignored in Fitting Libretto to the Music

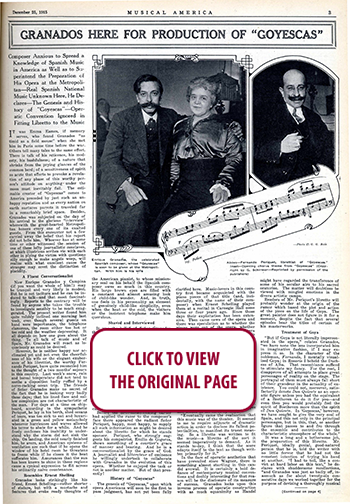

IT was Emma Eames, if memory serves, who found Granados “as timid as a field mouse” when she met him in Paris some time before the war. Others tell many tales to the same effect. There is talk of his reticence, his mode ty, his bashfulness; of a nature that brinks from the prying glances of the common herd; of a sensitiveness of spirit so acute that efforts to provoke a revelation of any phase of this worthy person’s attitude on anything under the moon must inevitably fail. The estimable creator of “Goyescas” comes to America preceded by just such an unhappy reputation and as every nation on earth nurtures parrots it traveled far in a remarkably brief space. Besides, Granados was subjected on the day of his arrival to the glorious “interview” wherewith the great-hearted Metropolitan honors every one of its exalted guests. From this encounter not a few carried away the belief that his report did not belie him. Whoever has at some time or other witnessed the session of one of these lofty journalistic conclaves, at which illustrious scribes vie with each other in plying the victim with questions silly enough to make angels weep, will realize with what excellent cause the stranger may covet the distinction of placidity.

A Fluent Conversationalist

Now Enrique Granados y Campina (if you want the whole of him!) may be tranquil and very likely is modest. But he is not taciturn and he can be induced to talk3and that most fascinatingly. Reports to the contrary will be found by anyone who takes the trouble to investigate sensibly to be much exaggerated. The present writer found him quite volubly inclined one morning last week, even though several guests on hand were importunate, the telephone clamorous, the room either too hot or too cold and the weather depressing. It all depends on how one goes about the thing. To all talk of music and of Spain, Mr. Granados will react as loquaciously as could be desired.

However, he is neither happy nor acclimated yet and not even the cheerfulness of his wife or the elegant exuberance of his librettist, the worthy Fernando Periquet, have quite reconciled him to the thought of a two months’ sojourn in this country. Last week’s snow, rain and boreal temperature did not tend to soothe a disposition badly ruffled by a nerve-racking ocean trip. The friends of Señor Granados make no secret of the fact that he is looking very badly these days; that his lined face and sallow complexion are not characteristic of the man. For days at a time on shipboard, according to the sympathetic Periquet, he lay in his berth, shed oceans of tears, was too sick to eat and luxuriated in a green and yellow melancholy whenever hurricanes and waves allowed his terror to abate for a while. And he freely confesses his inability to understand why the storm did not sink the ship. On landing, the cold nearly finished him, he avers, and American systems of ventilation are such that if he opens the window of his hotel room he threatens to freeze while if he closes it the heat suffocates him. Assurances that the sun has been known to shine in these regions cause a cynical expression to flit across his ordinarily naïve countenance.

Resembles Ernest Shelling

Granados looks strikingly like his friend, Ernest Schelling—rather shorter of stature, but with a mustache and features that evoke ready thoughts of the American pianist, to whose missionary zeal on his behalf the Spanish composer owes so much. His large brown eyes are filled with a constant and almost amusing look of child-like wonder. And, in truth, one feels in his personality an element of genuinely child-like simplicity, even when the heat or the cold, the visitors or the insistent telephone make him querulous.

Shaved and Interviewed

It was the belief of Señor Granados that in America the individual interviewed deferred to the interviewer’s convenience and pleasure to the extent of seeking him out at the newspaper office instead of receiving him with more or less amiable condescension at his own domicile. Hence the writer, calling at the appointed hour, found him fuming and fretting in his anxiety to be on time at the offices of MUSICAL AMERICA. Apprised that the national custom did not favor such concessions to the bodily wellbeing of minions of the press, he rejoiced inwardly and summoned the barber. Ensconced in a plush armchair in the drawing room of his suite he suffered himself, with the best grace in the world, to be shaved and questioned at the same time. He speaks no English, but those who have no Spanish at their command can meet him on equal terms in French.

Before the determined-looking barber had applied the razor to the composer’s face there appeared the radiant Señor Periquet, happy, most happy, to supply all such information as might be desired about the libretto for which he stands sponsor. Periquet, who strongly suggests his compatriot, Emilio de Gogorza, shows something of a courtier’s grace of manner and bearing. And he is a conversationalist by the grace of God. A journalist and litterateur of eminence he willingly undertook to collaborate with Granados in the evolution of this opera. Whether he enjoyed the task or not is another matter. But of that presently!

History of “Goyescas”

The genesis of “Goyescas,” upon which opera Americans will soon be the first to pass judgment, has not yet been fully clarified here. Music-lovers in this country first became acquainted with the piano pieces of that title (and, incidentally, with the name of their composer) when Ernest Schelling played them at a recital in Carnegie Hall some three or four years ago. Since those days their exploitation has been extensive. Then came news of the opera and there was speculation as to whether the pieces were out of the opera, whether they were sketches from which the opera was evolved or whether any relationship existed between them and the opera at all. And now the score of the latter is available and it is seen to consist largely of the much-admired piano pieces.

Thus the composer’s elucidation:

“About seventeen years ago I put forth a work which failed. It doubtless deserved failure; nevertheless, I was broken-hearted over the matter. Whatever may have been its faults as a whole, I felt convinced of the value of certain portions of it and these I carefully preserved. In 1909 I took them up once more, reshaped them into a suite for piano. The conception I had sought to embody in this music was Spain—the abstract sense and idea of certain elements in my country’s life and character. And I had in mind, coincidentally, types· and scenes as set forth by Goya.

“Eventually came the realization that this music was of the theater. It seemed to me to require adjuncts of dramatic action in order to disclose its fullest potentialities, to manifest its truest meaning. So a libretto was written to fit the music—a libretto of the sort it seemed imperatively to demand. As it stands to-day, I think that the score adapts itself to the text as though written primarily for it.”

In the face of operatic aesthetics that have prevailed since Wagner, there is something almost startling in this candid avowal. It is certainly a bold defiance of contemporary musical conventions and doubly interesting for that reason will be the disclosure of its measure of success. Granados looks upon this inverse process of operatic construction with as much equanimity as Handel might have regarded the transference of some of his secular airs to his sacred oratorios. The matter will doubtless be viewed with mingled emotions in the divers artistic camps.

Readers of Mr. Periquet’s libretto will probably wonder at the origin of the rumor which based the plot and action of the piece on the life of Goya. The great painter does not figure in it for a moment, despite the fact that several episodes bear the titles of certain of his masterworks.

Treatment of Goya

“But if Goya is not literally impersonated in the opera,” relates Granados, “we have none the less incorporated him in imaginative fashion, if I may express it so. In the character of the nobleman, Fernando, I mentally visualized Goya; in Rosario I beheld the Duchess of Alba. That resemblance sufficed to stimulate my fancy. For the rest, I disapprove of all attempts to place great personages of reality on the stage. The portrayal of them must always fall short of their grandeur in the actuality of existence. You could not, moreover, satisfactorily denote Don Quixote as an operatic figure unless you had the equivalent of a Beethoven to do it for you—and even then you would probably feel the spirit of Beethoven more than the spirit of Don Quixote. In 'Goyescas,' however, we have sought to give the very soul of Spain, and this not only in the principal personages, but in this, that, or another figure that passes to and fro through the ensemble and contributes to the characteristic atmosphere of the whole.”

It was a long and a bothersome job, the preparation of this libretto. Mr. Periquet, ideally genial, good-natured person that he is, told the writer with no little fervor that he had not the remotest intention of trying his hand at another. “I had to toil, like a convict at hard labor on this text,” he declares with shudder-some recollections, “and Granados was just as badly off, inasmuch as for about twenty-six consecutive days we worked together for the purpose of devising a thoroughly musical and singable poem. I wrote it originally in my own fashion and without regard for musical exigencies. Of course, I knew that much reconstruction would be required, but the work it did involve was simply fearful. I believe we rewrote the thing six or seven times before we got what satisfied us. But once in shape, words and music fitted admirably.”

All of which reminds one of Weber, Helmine von Chezy and “Euryanthe” with all due apologies to Mr. Periquet!

May Give Piano Recitals

If the nostalgic yearnings of Composer Granados are not too irrepressible, there is a possibility that he may tarry awhile, after the launching of his opera, for some piano recitals.· His gifts as a pianist are freely admitted abroad and he would unquestionably be listened to with unconcealed interest here. His aim, in such an event, would be to spread the gospel of Spanish music in America.

“For you, like so many other people,” he declares, “know nothing of the real musical contributions of Spain. The musical interpretation of Spain is not to be found in tawdry boleros and habaneras, in· Moszkowsi, in “Carmen,” in anything that has sharp dance rhythms accompanied by tambourines or castanets. The music of my nation is far more complex, more poetic and subtle.

“We have a number of extremely talented young composers. The principal drawback in their work is the tendency to ally themselves to some foreign school. Thus one leans on Wagner, another on Debussy. Albeniz himself, a man of tremendous gifts, did not accomplish all he might have for a national Spanish school through his adoption of French methods and his total subservience to modern Parisian models by the time he wrote ‘Iberia.’ It is a pity, for his genius was pronounced. One great composer we have of ingrained nationalism, the wonderful octogenarian, Felipe Pedrell, who was one of my masters, and whom one might call the Spanish Glinka.

“For myself I have always shunned imitation of the methods of any one established school of composition. I have allowed myself to develop spontaneously, never seeking to accomplish this effect or that in a fashion alien to my personality and always keeping the ideal of nationalism in mind. Great, to my mind, is the future of Spanish composition. It is gathering strength at present and I feel certain that, at the close of the war, when art as a whole will be forced to take a new start everywhere, it will step into its proper place, untrammeled by long established competition, and rejuvenate the art of music by its freshness, novelty and wholesome beauty.” —H. F. P.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO