100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (366)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (366)

November 20, 1920

Page 2

CARUSO ACCLAIMED AS METROPOLITAN LAUNCHES SEASON

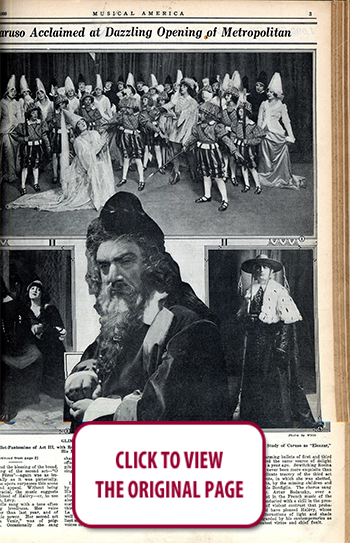

King of Tenors Triumphs in “La Juive”—Shares Stellar Glory with Rosa Ponselle and Leon Rothier—Cast, with One Exception, Same as Last Year’s—Gorgeous Pageantry on Stage Matched by· Brilliance of Audience—Capacity Throng Recalls Principals Many Times

By OSCAR THOMPSON

OPERA—that other name for joy—at last is unconfined. The Metropolitan is irradiate once more. The season has taken the high road and is proceeding blithely on its way, after an opening night of the traditional scintillance, suspense and suffocation. Caruso is—as he always was and ever shall be—Caruso: The diamond horseshoe is no less transplendent. The standee is in his heaven. All’s right with the world!

The perspicacious Gatti-Casazza made no mistake. Halévy’s “La Juive”—the gorgeously caparisoned revival carried over from last season—was his logical salutatory, in spite of the three and a half hours of it. It matched glitter with glitter and gave sigh for sigh. With its pageantry and its exceptional opportunities for the king of tenors, it was ordained for just such spectacular duty as it was called upon to do on Monday night. Oracular powers scarcely were needed to prophesy as much when the dust was blown from its covers a year ago. From its churchly opening to its grisly close, “La Juive” embodies the qualities—save brevity—regarded as most desirable in a first night opera. A further cut has been made in the first scene of the fourth act, and—long as the work still is—early departures were not more than customarily numerous. Of course not a third of the audience was seated when the first curtain parted.

It has been said of successive opening nights at the Metropolitan that all are alike, save that the latest one always is more dazzling than all that have gone before, and by inference, any that are likely to follow after. This one was preluded in the morning by a swirl of snow, but Boreas blew too faintly to interfere with social pomp and circumstance. The cast was virtually that of last year: Ponselle, Scotney, Caruso, Harrold, Rothier, Leonhardt and Ananian. There was the expected capacity throng which did not need the assistance it received from the claque in bringing on the inevitable recalls for the participants. At the last of these, Eleazar doffed his nose, and again was Enrico, even behind his boscage of beard.

What matters it on an opening night if some of the principals are not in midseason form, or the musical fare is a curious commingling of haunting and only half captured melody, heavy-footed recitative and opera comique!

Of Halévy’s music, it was Richard Wagner who said it represented a “praiseworthy striving after simplicity.” He gave Halévy credit for having “banished all those perfidious little tricks and intolerable prima donna embellishments which had flown from the scores of Donizetti and his accomplices into the pen of French opera.” To-day, the melodies of Halévy have a wistful elusiveness which gives them a charm long since vanished from many franker and bolder tunes of his day. Monday night it was again proved that for these moments of tender grace, when linked with a characterization such as Caruso’s, Metropolitan audiences gladly will abide the ponderous, senescent secco passages which serve to link the lyric scenes.

Stirring Triumph for Caruso

Time was when Caruso was regarded as a trumpet set for Verdi’s lips to blow. The greater Caruso—the singing-actor of to-day, whose powers of characterization keep pace with his vocal might—has come into his own with “La Juive.” His Eleazar, deeper and subtler than when he added it to his repertoire last season, has brought him to the summit of his career. Monday night he gave all he had to the role—brain, craft, personality, as well as voice. It was an unforgettable portrait, worthy of place with those dramatic impersonations which in the past have been associated with great baritones more frequently than with their tenor confrêres. Maurel or Renaud or Scotti might justly have been acclaimed for its craftsmanship. Vocally the tenor was not without the constraint and the faults of muscular propulsion which so curiously have gone hand in hand with his golden tone—now a darker gold, to be sure, but still the most precious of metals. This tonal opulence was expended with all the Caruso prodigality in the long fourth act air, “Rachel Quand Seigneur,” and the moving’ eloquence of the lament brought the peak of the evening’s enthusiasm. He labored somewhat in the first act, though there was the familiar outburst of frenzied approbation after “O ma Fille Cherie,” in the finale. This, in spite of some uncertainty in the attack of his upper tones, which sounded jagged and lacking their old-time resonance. The real test of Caruso’s powers came later, however, and was met in a way to dispel all misgivings as to his condition for the season. His mezzo voce was of surpassing beauty. The prayer and the blessing of the bread, at the opening of the second act—”O Dieu de nos Pères” —again was as impressive vocally as it was pictorially. Nothing in the opera surpasses this scene in beauty and appeal. Without being imitatively racial, the music suggests the Hebraic blood of Halévy—or, to use his real name, Lévy.

Miss Ponselle sang with a tone often of caressing loveliness. Her voice seemed larger than last year, and of more dramatic power. Her second act air, “Il Va Venir,” was of poignant charm. Occasionally she sang sharp on upper tones, by way of offsetting the several deviations from pitch in the opposite direction in the singing of Orville Harrold.

Rothier Admired as “Cardinal”

Leon Rothier evoked only admiration by his noble portrayal of the Cardinal. His sonorous voice redeemed many of the attenuated recitatives in which the score abounds; and his singing of the dramatically impressive malediction in the third act, and the first act cavatina, “Si La Rigeur,” had authority of style as well as vocal richness. One of the loveliest moments of the opera came when the voices of Ponselle and Caruso were united with Rothier's in the latter portion of "Si La Rigeur," the cavatina broadening into a well-written ensemble.

Though not in his best voice, Orville Harrold did what he could with the part of Leopold, at best an ungrateful one. The second act trio, in which he sang with Caruso and Ponselle—“Je Vois Son Front Coupable”—was gratefully sung. Statuesque Evelyn Scotney again was the Princess Eudoxia, and, as last year, was more attractive to the eye than her well-managed but miniature and colorless voice was stimulating to the ear. Robert Leonhardt, in the rôle of Ruggiero—last season assigned to Thomas Chalmers—returned to friends of other years.

The charming ballets of first and third acts proved the same source of delight they were a year ago. Bewitching Rosina Galli has never been more exquisite than in the delicate tracery of the third act divertimento, in which she was abetted, as hitherto, by the miming children and the capable Bonfiglio. The chorus sang admirably. Artur Bodanzky, ever a precisionist in the French music of the period, conducted with a skill in the presentation of violent contrast that probably would have pleased Halévy, whose sharp alternations of light and shade were regarded by his contemporaries as his greatest virtue and chief fault.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO