100 YEARS AGO...IN MUSICAL AMERICA (115)

100 YEARS AGO...IN MUSICAL AMERICA (115)

October 30, 1915

Page 9

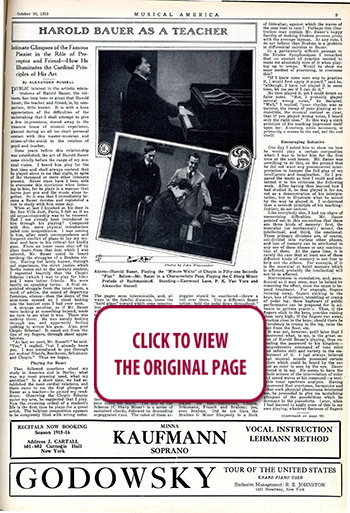

HAROLD BAUER AS A TEACHER

Intimate Glimpses of the Famous Pianist in the Rôle of Preceptor and Friend—How He Illuminates the Cardinal Principles of His Art

By ALEXANDER RUSSELL

PUBLIC interest in the artistic ministrations of Harold Bauer, the virtuoso, has long been so great that Harold Bauer, the teacher and friend, is, by comparison, little known. It is with a keen appreciation of the difficulties of the undertaking that I shall attempt to give a few impressions, stored away in the treasure house of musical experience, gleaned during an all too short personal contact with this master-musician and citizen-of-the-world in the relation of pupil and teacher.

Some years before this relationship was established, the art of Harold Bauer came vividly before the range of my musical vision. I heard him play for the first time and shall always contend that he played alone to me that night, in spite of the thousand or more other listeners present. Never since have I been able to overcome this conviction when listening to him, for he plays in a manner that leaves just you and the music alone together. So it was that I immediately became a Bauer devotee and registered a vow to study with him some day.

When at last I knocked on his door in the Rue Ville Just, Paris, I felt as if an old acquaintanceship was to be renewed. Had I not already been introduced to him through his playing? Compared with this, mere physical introduction paled into insignificance. I was coming to him, after much correspondence and frequent conflict of plans to lay my musical soul bare to his critical but kindly gaze. From an inner room shut off by glass doors from that into which I was ushered, Mr. Bauer could be heard soothing the struggles of a Brahms victim. Having but lately known, through sad experience, the strict justice which Berlin metes out to the unwary student, I regretted heartily that the Chopin Scherzo (which I was to play for him) and I were better friends. We were hardly on speaking terms. A final anguished struggle from the inner room, a word of advice, the sound of departing footsteps, silence—then the doors of the ante-room opened an I stood looking into the keenest eyes I had ever seen.

A strange sensation, as if Mr. Bauer were looking at something beyond, made me turn to see what it was. There was nothing there. He was merely looking through me, and apparently finding nothing to arrest his gaze. Alas, poor Chopin Scherzo! It oozed out from the tips of my fingers, through sheer apprehension.

“At last we meet, Mr. Russell!” he said. “Yes,” I replied, “but I already know you. I was introduced to you through our mutual friends, Beethoven, Schumann and Chopin.” Thus we began.

Playing for Bauer

Then followed questions about my study in America and in Berlin; what was my most pressing need, what my ambition? In a short time, we had established the most cordial relations, and there came to me the first glimpse of Bauer as a teacher—he gained my confidence. Observing the Chopin Scherzo under my arm, he suggested that I play. Now the crowning ordeal of a student's life is the first time he plays for a great artist. The helpless composition appears to be completely filled with wrong notes. The pages seem interminable, and, always in the fateful distance, looms the “hard place” toward which some remorseless current of sinister power drives him with appalling speed. Never does the heart beat so freely or the breath come so easily as when, with set teeth and perspiring brow, he somehow sweeps past the dread spot and comes to anchor in the quiet haven which marks the end of the piece.

Mr. Bauer's first remark when I had ceased to irritate the welkin showed me the second great principle of his teaching. “That was very good. I should say you have sufficient ·technique. Rather than try to give you more just now, I·shall try to make what you have more useful to you.” He was not interested in finding out how little I knew, but in how much I could learn. Later I learned that this principle logically included a third: When that which you have already acquired is made more useful to you, you have already added to your store both of technique and musical knowledge.

His next criticism was a direct application of this principle: “You articulate all your notes too much. The trio of· the Scherzo (C Sharp Minor) is a series of sustained chords, followed by descending arpeggiated runs. The notes of these arpeggios should be smothered—throw a veil over them. Use a different finger action; hold the pedal down throughout.” I had been carefully picking out each note with conservatory correctness of curved fingers. He then played the passage for me, and at once a fourth principle became clear: The value of tonal and color contrasts produced by different kinds of finger touch.

To illustrate this, Mr. Bauer played for me the opening measures of the “Waldstein” Sonata, remarking that it was quite admissible, of course, to play it in a different manner, but that it was always essential that there should be contrasts in the tone qualities produced in the various phrases. Thus, “the study of technique should be based upon its value as a means of expression, for in itself without relation to its employment, it is nothing. These illustrations served to stimulate my imagination to such an extent that it was filled with a vision of endless possibilities in tone-painting. Thus a fifth principle was revealed: He awakened the imaginative faculty. This was true of everything I played for him—Beethoven, Chopin, Schumann, Franck and Brahms; yes, even Brahms. Did he not liken the Brahms G Minor Rhapsody to a Rock of Gibraltar, against which the waves of the seas beat in vain? Perhaps this illustration may explain Mr. Bauer’s happy faculty of making Brahms persona grata with the average layman. At any rate, I do not believe that Brahms is a problem in differential calculus to Bauer. In a particularly difficult passage in the Etudes Symphoniques I remarked that no amount of practice seemed to make me absolutely sure of it when playing up to tempo. Would he show me some method of practicing, to overcome this?

“If I knew some sure way to practice it, I would first apply it myself,” said he, “although, I have not played it in some time, let me see if I can do it.”

He then played it, yet I could detect no false notes. “But, I probably played several wrong notes,” he declared. “Well,” I replied, “your rhythm was so incisive, the sweep of your playing so irresistible, the musical content so clear, that if you played wrong notes, I heard only the right ones.” In this way a sixth principle of his teaching impressed itself upon me: Accuracy, while necessary, is primarily a means to the end, not the end itself.

Encouraging Initiative

One day I asked him to show me how he would play a certain·composition which I was to bring him for the first time at the next lesson. Mr. Bauer was unwilling to do this, on the ground that he did not want any preconceived interpretation to hamper the full play of my intelligence and imagination. So I prepared the music as best I could and submitted it to his criticism the following week. After having thus learned how I had studied it, he then played it for me, not as a demonstration of his interpretation, but to illustrate what he meant by the way he played it. I understood then a seventh principle of his teaching: Initiate, do not imitate.

Like everybody else, I had my share of memorizing difficulties. Mr. Bauer pointed out in this connection that there are three kinds of memory: first, the muscular (or mechanical),·second, the intellectual, and third, the emotional. These primary divisions are, of course, sub-divided into various other phases, and loss of memory can be attributed to any one of these phases or any combination of them. At the same time, it is rarely the case that at least one of these different kinds of memory is not free to help out the others. For example, if it is the muscular or habit memory which is affected, probably the intellectual will not be so affected.

Nervousness is cumulative, and, paradoxical as it may seem, mav be helped bv removing the effect, since the cause is beyond treatment. For example, fingers running away, fingers sticking to the keys, loss of memory, trembling or cramp of pedal leg; these bugbears of public performance can be prepared for in advance in private practice. Thus, if the fingers stick to the keys, practice raising them very high; if the fingers run away, practice close to the keys; should there be a tendency to cramp in the leg, raise the heel from the floor, etc.

It was not, however, until later that I discovered what, to me, is the great secret of Harold Bauer's playing, thus revealing the password to his kingdom—comprehensive command of tone color and infinite skill and variety in the employment of it. I had always believed that musical sounds possessed certain colors which could be heard by the ear just as color is seen by the eye. Bauer proved it to me. He seems to have the whole science of the interrelation of color and sound waves at his command—a veritable tonal spectrum analysis. Having discovered that overtones, harmonics and other such physical phenomena interested me, he proceeded to give me tantalizing glimpses of the possibilities which lie dormant in the pianoforte. Later, when I had learned to apply some of this to my own playing, whatever fleetness of fingers I had acquired took on a new meaning. In this connection I learned several important things:

The notes produced by a violin sound dissimilar, therefore the violinist should endeavor to make them sound as much alike as possible. The notes produced by a piano are similar in sound, therefore the pianist should endeavor to make them sound unlike. (According to this, most piano teaching of to-day is done backwards!)

Three Kinds of Noises

There are three kinds of noises produced by the pianist—the impact of the finger upon the key, the sound of the key against the key bed, the sound produced by the hammer against the string. These three distinctive sounds can be combined so as to produce qualities of various character.

The five fingers of the hand normally produce five different kinds of tone quality; luckily, no amount of technical exercise will ever make this physiological phenomenon entirely disappear.

Mr. Bauer also showed me the mysteries of the interrelation of intervals within any given chord, that is, the colors produced by emphasizing one or two notes more than the rest. By such means I have heard him produce an actual snarl of tone (introduction to F Sharp Minor Sonata of Schumann) and an ethereal floating zephyr from two chords spilled four octaves apart (Etudes Symphoniques). At times he kept the damper pedal vibrating almost incessantly, in a manner not unlike the violinist’s vibrato. Anent this, he remarked: “There are pianists who say that the pedals are not essential. The pedals are the lungs of the instrument. ” Small wonder some piano playing sounds tubercular!

“The piano,” Mr. Bauer continued at another lesson, “is a mechanical instrument, therefore nothing of the physical characteristics of the performer enter into it; the case with the voice is exactly opposite. However, such individual characteristics can be approximated in piano playing.” For instance, one day, while playing the Handel-Brahms Variations, he suggested that a particular variation should sound “chubby.” (“Ah, Mr. Bauer, one must be chubby like you to play it like that!”) Another time he said: “Certain musical phrases inevitably suggest gesticulation, like t hose of an orator or an actor—this one (pointing to the music) is the shaking of a clenched fist; that one, a farewell wave of the hand, etc.” It was with great relief that I heard him tell a fellow-student: “It is a good thing to be a little nervous in public playing; it gives a certain vitality—a higher keying-up, which might otherwise be absent.”

After you have finished with your lesson, if there are no others to follow, sometimes you may be admitted to an inner circle. If so, he will then bring out a curious little box, lift the lid, and offer you a Russian cigarette, made especially after his own recipe. Then, woe to you if your wits be not more nimble than your fingers, for Mr. Bauer wants you to talk to him!

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO