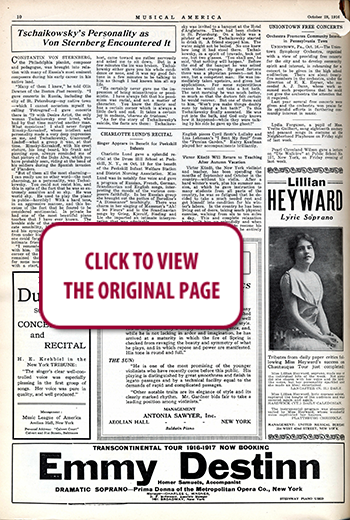

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (167)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (167)

October 28, 1916

Page 10

Tschaikowsky’s Personality as Von Sternberg Encountered It

CONSTANTIN VON STERNBERG, the Philadelphia pianist, composer and pedagogue, was brought into relation with many of Russia’s most eminent composers during his early career in his native land.

“Many of them I knew” he told Olin Downes of the Boston Post recently. “I gave concerts in Russia, including the city of St. Petersburg—my native town—which I cannot accustom myself to calling ‘Petrograd’—I gave concerts there in ‘79 with Desire Artot, the only woman Tschaikowsky ever loved, who had by that time married another man. What musicians! I shall never forget Rimsky-Korsakoff, whose intellect and personality made a very deep impression on me, and Tschaikowsky, Glazounoff, Liadoff—what a group it was, at that time. Rimsky-Korsakoff, with his erect stature, his long beard, his frank and piercing eyes, always reminded me of that picture of the Duke Alva, which you have probably seen, riding at the head of his soldiers during the Spanish invasion of Flanders.

“But of them all the most charming—I can really use no other word—the most charming, as a personality, was Tschaikowsky. You could not resist him, and this in spite of the fact that he was so extremely sensitive and so shy. He was world shy. He used to play the piano in public—horribly! With a hard tone, in an aggressive manner, and this because of the fact that he feared to be considered sentimental. In private he had one of the most beautiful piano touches that I have ever known. The lovable side of the man, his most delicate sensibility, his artistic perception and his sympathetic individuality came from under his fingers in a way that no one could forget who heard him play to intimate friends.

“I remember well my first meeting with him. He was standing off in one corner of the room when I entered and remained there, distrait, embarrassed for some moments, and then suddenly, with a start, realized his duties as a host, came toward me rather nervously and asked me to sit down. But in a few minutes the ice was broken. Tschaikowsky either gave you his whole confidence or none, and it was my good fortune in a few minutes to be talking to him as though I had known him all my life.

“He certainly never gave me the impression of being misanthropic or pessimistic. I have always felt that his pessimism was racial, and not a matter of character. You know the Slavic soul has a certain corner which is always a little dark and sad. It takes a certain joy in sadness, ‘charme de tristesse.’

“As for the story of Tschaikowsky’s suicide, the facts are these: Tschaikowsky was invited to a banquet at the Hotel d’Angleterre. There had been cholera in St. Petersburg. On a table was a pitcher of water. Tschaikowsky started to drink it. A friend stopped him. The water might not be boiled. No one knew how long it had stood there. Tschaikowsky, in a spirit of bravado, took not one, but two glasses. ‘You shall see,’ he said, ‘that nothing will happen.’ Before the end of the banquet he was seized with violent cramps. By good fortune there was a physician present—not his own, but a competent man. He was immediately taken upstairs, and given hot applications. · For some superstitious reason he would not take a hot bath. The next morning he was much better, so much so that the doctors felt certain he would recover. But one of them said to him, ‘Won’t you make things doubly sure by taking a hot bath?’ To this Tschaikowsky finally assented. He was put into the bath, and God only knows how it happened—while they were talking by his side he gave up the ghost!

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO