100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (177)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (177)

January 6, 1917

Page 9

How Gatti-Casazza Helped An Old Donizetti Opera Find Its Second Youth

By GIULIO GATTI-CASAZZA

[From the New York Times]

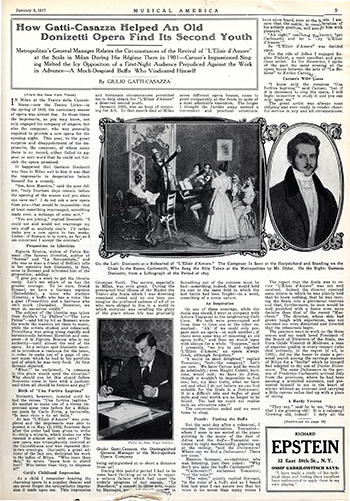

Metropolitan’s General Manager Relates the Circumstances of the Revival of “L’Elisir d’Amore” at the Scala in Milan During His Régime There in 1901—Caruso’s Impassioned Singing Melted the Icy Opposition of a First-Night Audience Prejudiced Against the Work in Advance—A Much-Despised Buffo Who Vindicated Himself

IN Milan at the Teatro della Cannobbiana—now the Teatro Lirico—in the spring of 1832, the customary season of opera was almost due. In those times the impresario, as you may know, not only engaged his company of singers, but also the composer, who was generally required to provide a new opera for the opening night. This year, to the great surprise and disappointment of the impresario, the composer, of whose name there is no record, either failed to appear or sent word that he could not furnish the opera promised.

It happened that Gaetano Donizetti was then in Milan and to him it was that the impresario in desperation betook himself for a remedy.

“See, here Maestro,” said the poor fellow, “only fourteen days remain before the opening of the season and you alone can save me! I do not ask a new opera from you—that would be impossible—but at least something rearranged, something made over, a mélange of some sort.”

“You are joking,” replied Donizetti. “I could not and would not rearrange my own stuff or anybody else’s. I’d rather make you a new opera in two weeks. Listen: if Romani is in town, as far as I am concerned I accept the contract.”

Proposition to Librettist

Signora Branca, widow of Felice Romani (the famous librettist, author of “Norma” and “La Sonnambula,” and who was so dear a friend of Bellini) tells in her memoirs how Donizetti, in fact, came to Romani and informed him of the proposition, adding:

“I give you a week to get the libretto ready. Let’s see which of us has the greater courage. To be sure, friend Romani, we have a German soprano (Heinefelder), a tenor who stutters (Genero), a buffo who has a voice like a goat (Frezzolini) and a baritone who isn’t much (Dabadie). However, we must do ourselves credit.”

The subject of the libretto was taken from Scribe’s “Le Philtre”—”The Love Potion”—and bit by bit as Romani wrote the words the maestro set them to music, while the artists studied and rehearsed. Everything was going along rapidly and harmoniously between librettist and composer—it is Signora Branca who is my authority—until almost the end of the opera. At a certain spot Donizetti wanted to introduce a romanza for the tenor, in order to make use of a page of concert music which he had in his portfolio and of which he was very fond. At first Romani objected.

“What!” he exclaimed; “a romanza in this place would spoil the situation! Why should you let this stupid fellow Nemorino come in here with a pathetic wail when all should be festive and gay?”

Birth of “Una Furtiva Lagrima”

Donizetti, however, insisted until he had the verses “Una furtiva lagrima.” He wanted to make use of a theme improvised some time before for a Milanese poem by Carlo Porta, a barcarolle, “Io sono ricco e tu sei bella.”

At last “L’Elisir d’Amore” was completed and the impresario was able to present it on May 12, 1832, fourteen days after the order had been given to write it—truly a miracle, which makes me who recount it almost melt with envy! The new opera was triumphantly received at the Cannobbiana and was repeated thirty-two evenings. Donizetti, a great admirer of the fair sex, dedicated his work to the ladies of Milan. “Who more than they,” he wrote, “know how to distill love? Who better than they, to dispense it?”

Gatti’s Childhood Impression

As a child I remember hearing the charming opera in a popular theater and can never forget the sympathetic impression it made upon me. This impression and fortunate circumstances permitted me to help obtain for “L’Elisir d’Amore a deserved second youth.

January, 1901, was an hour of mourning for Art. In that month died at Milan Giuseppe Verdi. The sorrow, especially in Milan, was very great. During the protracted final illness of the Master the Teatro alla Scala which I was directing remained closed and no one here can imagine the profound sadness of all of us who were obliged to live in a world in which everyone was recalling the glory of the giant whose life was gradually being extinguished at so short a distance from us!

During this painful period I had to do some hard thinking as to how to repair a serious failure which had upset the orderly progress of our season. “Le Maschere,” a comedy in three acts, music by Mascagni produced simultaneously in seven different opera houses, came to grief irreparably at the Scala in spite of a most admirable execution. The longer I thought the further away seemed a convenient and practical substitute. Something out of the commorn must be had—something, indeed, that would hold its own in the same field in which the last battle had been fought—in a word, something of a comic nature.

An Inspiration

On one of these evenings, while the Scala was closed, I went in company with Arturo Toscanini to the neighboring Café Cova. We both were preoccupied and from time to time one or the other remarked: “Ah! if we could only prepare such an opera—or such another; if there were some way of mounting an old opera buffa,” and then we would lapse with silence for a while. “Suppose,” said I presently, “we try to put together ‘L’Elisir d’Amore,’ an opera always fresh, although forgotten.”

“I would be most delighted,” replied Toscanini; “but—the company? Let’s see now. We have Caruso and he would do admirably; even Magini Coletti, baritone, would suit; we have no Adina, though it wouldn’t be impossible to find one; but, my dear Gatti, what we have not and what I do not believe we can find suitable for the Scala is a Dulcamara. It is a difficult role and buffos of good style and real worth are no longer to be found. Too bad we could not realize such an attractive idea!”

The conversation ended and we went home to sleep.

Puzzle: Finding the Buffo

But the next day after a rehearsal, I resumed the conversation. Toscanini—whom I seem to see seated at the piano pointing to the music of the duet of Adina and the buffo—Toscanini continued to reply mechanically, glancing up at the ceiling; “and the Dulcamara? Where can we find a Dulcamara? There are none.”

Maestro Sormani, co-répétiteur, who was listening, just then asked: “Why don’t you take the buffo Carbonetti?”

“Carbonetti!” exclaimed Toscanini; “but the voice!” “The voice,” quietly replied Sormani, “is the voice of a buffo and as I heard him last year I can assure you that his voice is no worse than many voices I have since heard, even at the Scala. I am sure that the public in consideration of his artistic qualities, will accept him with pleasure.”

“All right,” concluded Toscanini, “get Carbonetti and let him try ‘L’Elisir d’Amore.’”

So “L’Elisir d’Amore” was decided upon.

For the rôle of Adina I engaged Regina Pinkert, a most excellent and gracious artist. As for Nemorino, I spoke of the part the same evening at the opera house between the acts of “La Bohème” to Enrico Caruso.

Caruso’s Willingness

“I know only the romanza ‘Una furtiva lagrima,’ “said Caruso; “but if it is necessary to sing the opera, I will begin to-morrow to study it and you can rely upon me.”

The great artist was always most obliging and ever ready to render cheerful service in any and all circumstances.

The report that the Scala was to revive “L’Elisir d’Amore” was not well received. Indeed, the director received some letters in which he was plainly told that he knew nothing, that he was turning the Scala into a provincial teatrino and that, furthermore, he soon would be well punished with a fiasco even more decisive than that of the recent “Maschere.” The director, whose skin had grown tough with experience, was not alarmed nor even disturbed and directed that the rehearsals begin.

The painters went to work on the three scenes and my much loved President of the Board of Directors of the Scala, the Duca Guido Visconti di Modrone, a man of superior quality in every respect (who died untimely, to the regret of all, in 1903), did me the honor to make a personal search among the carriage makers of Milan for a “berlin” which he himself had adapted to the use of Doctor Dulcamara. The same Dulcamara in the person of Frederico Carbonetti arrived duly from the provinces, where he had been passing a wretched existence, and presented himself to me in the heart of winter without an overcoat and carrying a little canvas valise tied up with a piece of string.

A Hardy Veteran

“They say,” said he to me, “they say that I am growing old! It is a calumny! Growing old, indeed! I defy all the youngsters to travel around Italy as I do—in the cold weather and without an overcoat!”

Then he hurried off to the rehearsal, where Toscanini had a fine job to induce him to sing his part without adding top notes not in the score.

“Let me do that F sharp, Maestro,” begged Carbonetti. “Believe me, it is a fine note! Won’t you hear it?”

Toscanini laughed—grimly. He prepared the opera with scrupulous care and unapproachable good taste, but he was not satisfied and showed his discontent openly. As a matter of fact, he was justified. The voice of Dulcamara irritated him.

“My dear Gatti,” said he, “I fear we have made an unfortunate decision. However, may God send us good fortune!”

Many times I have seen Toscanini in ill-humor, but never in humor so forbidding as the morning of the day fixed for the première of “L’Elisir.” He entered my office, where by chance had come my father, who was passing through Milan. Scarcely saluting him, Toscanini handed me a letter, saying bitterly: See what a fine act of idiocy we are about to commit. Read this!”

Traveling Salesman as Critic

The letter, signed by a traveling salesman, bluntly said: “However could a maestro who has the reputation of being so exacting accept for the Scala an artist so impossible as Carbonetti—an artist whom the writer only a few weeks ago heard whistled off the stage of a provincial theater?”

We tried to convince Toscanini that the opinion of a single individual had only a relative value; that he shouldn’t concern himself too much about the letter; but he replied warmly:

“The traveling salesman is more intelligent than we are, and this evening the public will prove that he is right. That’s all I have to say,” and off he went, pulling his hat down on his nose and grumbling execrations.

In the evening it is not a large audience that attends the première, but what it lacks in numbers it more than makes up in its degree of ill humor and its readiness to teach a lesson to me, to the artists, and even to Donizetti, if necessary.

An Icy Attitude

Toscanini appears with his face still dark. He takes his place at the desk, and the opera commences. The chorus sings its strophes; Adina relates with grace and feeling the story of the love of Queen Isolde and the magic filter; Nemorino in a song sighs deliciously, but the public takes no interest and remains cold. Not even Belcore, whom the baritone Magini Coletti impersonates in a masterly manner, succeeds in softening the stern faces of those terrible subscribers of the Scala. The second scene—that is the concerted number with Adina, Nemorino, Belcore and the chorus—ends almost in silence. An ugly state of affairs!

Back on the stage I feel my blood freezing and I begin to fear that the evening will end disastrously. Through a peep-hole I watch the public and I see that it is in ill-humor and bored. I glance at Toscanini. He has regained his composure and is directing with his customary elegance and masterly style.

The duet begins and Adina is delivering her phrases delightfully, but when she finishes some murmurs of approval are suddenly repressed. Now it is Caruso’s turn. Who that heard him do not remember? Calm and conscious that at this point will be decided the fate of the performance, ·he modulated the reply, “Chiedi al rio perche gemente” with a voice, a sentiment, an art, which no word could ever adequately describe.

A Caruso Triumph

He melted the cuirass of ice with which the public had invested itself, little by little caught his audience, subjugated it, conquered it, led it captive. Caruso had not yet finished the last note of the cadenza when an explosion, a tempest of cheers, of applause, of enthusiasm on the part of the entire public, saluted the youthful conqueror. So uproariously and imperatively did the house demand a repetition that Toscanini, notwithstanding his aversion, was compelled to grant it. When the curtain fell, Nemorino and Adina had a triple ovation. During the intermission only Caruso was talked about, and the old subscribers compared him to Mario, to Guilini, to Gayarre, · and sang his praises.

To Toscanini, who came on the stage with a face less dark, I remarked: “It seems to me the battle is won.”

“All right,” he replied, “provided the quack doctor doesn’t smash the eggs in the basket.”

Mr. Gatti’s Unrest

I am so nervous that I do not feel like observing how Dulcamara—Carbonetti—gets along with the public, and I go beneath the stage, where I can hear nothing. There I pace to and fro like a bear in a cage. When at last I am sure that the cavatina is finished I gradually approach the steps leading to the prompter’s box and with a certain hesitation I ask our good Marchesi—now prompter at the Metropolitan—how did Carbonetti do?

“How did he do?” repeated Marchesi; “why, splendidly! He had a great reception and made even those who did not want to, laugh.”

Ah! this time there is no longer any·doubt—the ship is in port and safely at anchor. Even the old voice of Carbonetti meets with favor. The evening is a triumph in crescendo. Every number is applauded from now on. The romanza “Una furtiva lagrima,” interrupted at every phrase by exclamations of admiration, has to be repeated by Caruso, and the public almost insists upon its being sung a third time. The curtain falls for the last time. Toscanini comes on the stage. We are all thrilled with emotion and happiness. “Viva Donizetti!”

Toscanini, radiant as he was going before the curtain with the artists to thank the public, embraces Caruso and says to me: “Per dio! Se questa Napoletano continua a cantare cosi, fara parlare di se il mondo intero!” (“By heaven! if this Neapolitan continues to sing like this, he will make the whole world talk about him.”)

Otto H. Kahn’s Suggestion

One evening at the Metropolitan last season Otto H. Kahn, our worthy and most intelligent Chairman, after a performance of “Marta” said to me:

“With Caruso in such admirable form why should we not revive ‘L’Elisir d’Amore’?”

Mr. Kahn, as _we say in Italy, was inviting a goose to drink. I accepted his suggestion with enthusiasm. “L’Elisir” is one of the very few armori di teatro of which I am the faithful slave—”Elisir” with Caruso, be it understood.

Caro Don Enrico—I and many others have become—less young; but you, indeed, must have drunk the elixir of youth, because your voice and your art, constantly advancing toward perfection, have preserved the charm and the wonderful resources of that memorable night at the Scala. * * * To you and your art may the gods grant as much youth and glory as still smile upon the “Elisir d’Amore” of the great Italian Master!

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO