100 YEARS AGO ... IN MUSICAL AMERICA (35)

100 YEARS AGO ... IN MUSICAL AMERICA (35)

January 31, 1914

Page 5

HERBERT’S “MADELEINE” HAS ITS METROPOLITAN PREMIERE

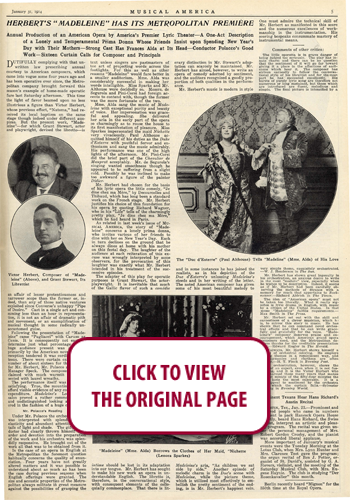

Annual Production of an American Opera by America’s Premier Lyric Theater—A One-Act Description of a Lonely and Temperamental Prima Donna Whose Friends Insist upon Spending New Year’s Day with Their Mothers—Strong Cast Has Frances AIda at Its Head—Conductor Polacco’s Good Work—Sixteen Curtain Calls for Composer and Principals

DUTIFULLY complying with that unwritten law prescribing annual courtesy to American composers, which came into vogue some four years ago and has been operative ever since, the Metropolitan company brought forward this season’s example of home-made operatic fare last Saturday afternoon. This time the light of favor beamed upon no less illustrious a figure than Victor Herbert, whose previous effort, “Natoma,” had received its local baptism on the same stage though indeed under different auspices. But the present work, “Madeleine”—for which Grant Stewart, actor and playwright, devised the libretto—is an affair of lesser pretentiousness and narrower scope than the former or, indeed, than any of those native ventures exploited since Converse’s unhappy “Pipe of Desire.” Cast in a single act and consuming less than an hour in representation, it is not an affair of dramatic pith and movement, or an exemplification of musical thought in some radically unaccustomed guise.

Following the presentation of “Madeleine” came “Pagliacci” with Caruso as Ganio. It is consequently not easy to determine just what percentage of the huge audience present was attracted primarily by the American novelty. The reception tendered it was cordially courteous. There were curtain calls to the number of about sixteen for the singers, for Mr. Herbert, Mr. Polacco and Stage Manager Speck. The composer was acclaimed with much warmth and presented with laurel wreaths.

The performance itself was generally satisfying. True, the mounting did not afford visible evidence of any considerable expenditure. Madeleine’s Louis XVI salon proved a rather common, garish and undistinguished looking affair, colored in the fashion of a huge chromo.

Mr. Polacco’s Reading

Under Mr. Polacco the orchestral score was interpreted with splendid spirit; elasticity and abundant attention to details of light and shade. The gifted conductor had clearly thrown himself with ardor and devotion into the preparation of the work and his orchestra was splendidly responsive. He brought out of the work all that was to be obtained from it.

In the case of an opera in English at the Metropolitan the foremost question habitually concerns the quality of enunciation. Four years have not greatly altered matters and it was possible to understand about as much as has been the case during previous seasons when English offerings were granted. The size and acoustic properties of the Metropolitan always militate in great measure against the possibilities of grasping the text unless singers are past masters of the art of projecting words across the footlights. For this as well as other reasons “Madeleine” would fare better in a smaller auditorium. Mme. Alda was considerably successful in making her words intelligible. Miss Sparks and Mr. Althouse were decidedly so. Messrs. de Segurola and Pini-Corsi had foreign accents to contend with; though the former was the more fortunate of the two.

Mme. AIda sang the music of Madeleine with exceptional purity and beauty of voice. Her impersonation was graceful and appealing. She delivered her aria in the early part of the opera so charmingly as to rouse the house to its first manifestation of pleasure. Miss Sparkes impersonated the maid Nichette very vivaciously. Paul Althouse acquitted himself of his duties as the Duke d’ Esterre with youthful fervor and enthusiasm and sang the music admirably. His performance was one of the highlights of the afternoon. Mr. Pini-Corsi did the brief part of the Chevalier de Mauprat acceptably. Mr. de Segurola’s singing wanted smoothness though he appeared to be suffering from a slight cold. Possibly he was inclined to make too awkward a figure of the painter Didier.

Mr. Herbert had chosen for the basis of his lyric opera the little comedy, “Je dine chez ma Mère,” by Decourcelles and Thibaud, which has long been a standard• work on the French stage. Mr. Herbert justifies his choice of this foundation for his opera by quoting Richard Wagner, who in his “Life” tells of the charmingly pretty play, “Je dine chez ma Mère,” which he had heard in Paris.

As related in last week’s issue of MUSICAL AMERICA, the story of “Madeleine” concerns a lonely prima donna, who invites various of her friends to dine with her on New Year’s Day. Each in turn declines on the ground that he always dines at home with his mother on this festal day. The laughter of the audience at each reiteration of this excuse was wrongly interpreted by some observers, for the provocation of this laughter was exactly what Mr. Herbert intended in his treatment of the successive episodes. The adapter of this play for operatic purposes is Grant Stewart, the actor-playwright. It is inevitable that much of the Gallic flavor of such a comédie intime should be lost in its adaptation into our tongue. Mr. Herbert has sought to make his new work an opera in understandable English. The libretto is, therefore, in the conversational style, with consequent elements of the colloquially commonplace. That there is literary distinction in Mr. Stewart’s adaptation can scarcely be maintained. Mr. Herbert has aimed, however, to write an opera of comedy adorned by sentiment, and the auditors recognized a goodly proportion of both qualities in the performance.

Mr. Herbert’s music is modern in style and in some instances he has joined the realists, as in his depiction of the Duc d’Esterre’s unloosing Madeleine’s steeds and in her writing of the letter: The noted American composer has given some of his most beautiful melody to Madeleine’s aria, “As children we sat side by side.” Another episode of melodic charm is the Duc’s scene with Madeleine, while the picture theme, which is utilized most effectively to embellish the pretty sentiment of the ending, is in Mr. Herbert’s happiest vein. One must admire the technical skill of Mr. Herbert as manifested in this score and the numerous excellences of workmanship in the instrumentation. His scoring bespeaks consummate mastery of instrumental means.

Comments of other critics:

The little operetta is in grave danger of being judged too seriously. The play has innate charm and there can be no question that the sentiment of it will go far toward giving .it a place in the affections of audiences which hear it. The composer has striven earnestly to follow the conversational style of his librettist and for the most part he has succeeded excellently. His bursts of purely lyric song are therefore not numerous or long sustained, but those which are introduced are fluent, melodious and simple. The final picture is intensified by a very simple theme, exquisitely orchestrated. —W. J. Henderson in The Sun.

Mr. Herbert has shown great ingenuity in his orchestration, an anxious desire to write in the most “modern” view, especially when he wishes to be descriptive. Indeed, it seems as if Mr. Herbert had been carefully observing the methods of Strauss with a memory for much that appertains to Beckmesser. —Richard Aldrich in The Times.

The idea of “American opera” must not be taken too literally. What it really signifies is lyric drama in English, with music by a citizen of the United States. In that sense “Madeleine” fulfills requirements. —Max Smith in The Press.

Mr. Herbert set out with the skill and earnestness of a clever musician, which he is, to mirror this story in music. He has shown that he can command novel orchestral effects and that he can write gracefully and gratefully for the voice. “Madeleine’s” composer deserves praise and encouragement, which American grand opera composers need, and the Metropolitan deserves thanks for the creditable presentation of it. —Edward Ziegler in The Herald.

As always, Mr. Herbert shows himself a master of orchestra l coloring. He employs leading themes in a reminiscent way, and his harmonies and rhythms are often piquant. —H.T. Finck in Evening Post.

The orchestration, however, shows the hand of an expert, even when it is not fascinating, and it is the Victor Herbert who has charmed these many years that makes the last minute of the fifty-four minutes the opera lasts the most enjoyable. It is a deft appeal to sentiment by the orchestra upon which the curtain falls. —Sylvester Rawling in Evening World.

Prominent Texans Hear Hans Richard’s Austin Recital

AUSTIN, Tex., Jan. 23. —Prominent and cultured people who came in numbers sufficient to pack Hancock Opera House recently, heard Hans Richard, the Swiss pianist, interpret an artistic and pleasing program. The recital was given under the personal management of Mrs. Robert Gordon Crosby, and the pianist was accorded liberal applause.

More important of January’s musical events were the Tuesday Morning at the Lotus Club, when Mrs. Lynn Hunter and Mrs. Clarence Test gave the program; the organ recital of Ben J. Potter, organist of St. David’s, assisted by G. A. Sievers, violinist, and the meeting of the Saturday Musical Club, with Mrs. Eugene Haynie. The club is studying “Der Rosenkavalier” this month.

Berlin recently heard “Mignon” for the 350th time at the Royal Opera.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO