100 YEARS AGO...IN MUSICAL AMERICA (79)

100 YEARS AGO...IN MUSICAL AMERICA (79)

January 30, 1915

Page 35

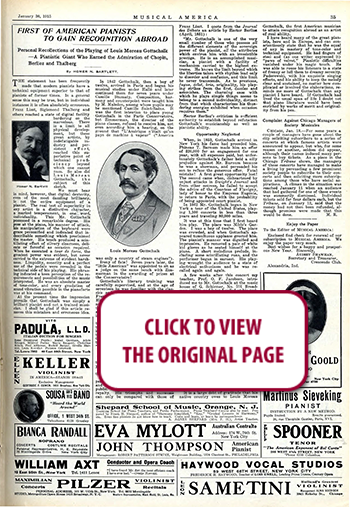

FIRST OF AMERICAN PIANISTS TO GAIN RECOGNITION ABROAD

Personal Recollections of the Playing of Louis Moreau Gottschalk—A Pianistic Giant Who Earned the Admiration of Chopin, Berlioz and Thalberg

By HOMER N. BARTLETT

THE statement has been frequently made that modern pianists have a technical equipment superior to that of pianists of former times. In a general sense this may be true, but in individual instances it is often absolutely erroneous. Franz Liszt, Sigismond Thalberg and others reached a state of digital facility bordering on the marvelous. There is a limit to all physical development, but these great artists, by indefatigable industry and persistent effort, reached this superlative point of technical proficiency beyond which one cannot pass. So also did Louis Moreau Gottschalk, the subject of this Homer N. Bartlett sketch.

We must bear in mind, however, that digital dexterity, even of the most dazzling brilliancy, is not the entire equipment of a pianist. The real test of superiority in any artist is a distinctive character, a marked temperament, in one word individuality. This Mr. Gottschalk possessed in a remarkable degree. His pose at the piano, his manner of attack his manipulation of the keyboard were grace personified and indicated that indescribable something which proclaimed the master. His touch produced a scintillating effect of silvery clearness, delicate or forceful as occasion required. When he executed a tour de force, the greatest power was evident, but never carried to the extreme of strident harshness. Limpidity, sonority and a perfect use of the pedals were revealed in the technical side of his playing. His phrasing indicated a keen perception of the requirements and possibilities of the music interpreted. He was an absolute master of tone-color, and every gradation of sound vibration possible in the pianoforte was at his command.

At the present time the impression prevails that Gottschalk was simply a brilliant pianist and not a trained musician. I shall be glad if this article removes this mistaken and erroneous idea.

In 1842 Gottschalk, then a boy of twelve, arrived in Paris and began his musical studies under Halle and later continued them for seven years under Camille Stumaty. Composition, harmony and counterpoint were taught him by M. Maledon, among whose pupils may be mentioned Camille Saint-Saëns. It was the first intention to place young Gottschalk in the Paris Conservatoire but Zimmerman, the director of the piano classes, refused to receive him, not even according him a hearing, on the ground that “L’Amerique n’etait qu’un pays de machine a vapeur” (“America was only a country of steam engines”).

Irony of fate! Seven years later, the “little American” was appointed to sit as a judge on the same bench with Zimmerman in the awarding of prizes at the Conservatoire!

Gottschalk’s literary training was carefully supervised, and at the age of seventeen he was familiar with the classics and could speak fluently English, French, German, Italian and Spanish. His association with the aristocracy and nobility of France and Spain gave him that ease of manner and distinguished air which were apparent to all who came in contact with him.

In 1845 Gottschalk, then a boy of sixteen, gave a private soirée, to which all the illustrious pianists of the day were invited, Chopin and Thalberg among them. The program comprised Chopin’s Concerto in E Minor, Thalberberg’s Fantaisie on “Semiramide” and Liszt’s on “Robert le Diable.”

Praise from Chopin

At the close of the recital Chopin extended his hand and said, “I predict that you will become the king of pianists.” Thalberg also gave the young player the highest encouragement.

From 1850 to 1852 Gottschalk appeared frequently in Paris, Switzerland and Spain, and became the idol of the public. He was frequently honored by royalty. His triumphs and successes can only be compared with those of Franz Liszt. I quote from the Journal des Débats an article by Hector Berlioz (April, 1851):

“Mr. Gottschalk is one of the very small number of those who possess all the different elements of the sovereign power of the pianist, all the attributes which environ him with an irresistible prestige. He is an accomplished musician, a pianist with a facility of mechanism carried to the highest extreme. He knows the limit beyond which the liberties taken with rhythm lead only to disorder and confusion, and this limit he never transcends. As to prestesse, fugue, éclat, brio, originality, his playing strikes from the first, dazzles and astonishes. The charming ease with which he plays simple things seems to belong to a second individuality, distinct from that which characterizes his thundering energies exhibited when occasion requires them.”

Hector Berlioz’s criticism is sufficient authority to establish beyond refutation Gottschalk’s musicianship as well as pianistic ability.

Opportunity Neglected

When, in 1853, Gottschalk arrived in New York his fame had preceded him. Phineas T. Barnum made him an offer of $20,000 for an engagement for one year, with all expenses paid, but unfortunately Gottschalk’s father held a silly prejudice against Mr. Barnum because he was a showman, and persuaded his son to refuse the generous offer. Fatal mistake! A first great opportunity lost! The second came when, disheartened by unjust attacks in Dwight’s Journal -and from other sources, he failed to accept the advice of the Countess of Flavigny, lady of honor to the Empress Eugénie, to return to Paris, with the probability of being appointed court pianist.

In 1862 Mr. Gottschalk began in New York a tour of the United States, playing 1,100 concerts in less than three years and traveling 80,000 miles.

It was at this time that I first heard him play. The place was Niblo’s Garden. I was a boy of twelve. The place was crowded, and when Gottschalk appeared tumultuous applause greeted him. The pianist’s manner was dignified and impressive. He removed a pair of white kid gloves .as he seated himself at the piano. A short melodious prelude, including some scintillating runs, and the performer began in earnest. His playing wrought the audience to a state of electrical enthusiasm and he was recalled again and again.

A few weeks after this concert my teacher, Prof. 0. F. Jacobsen, introduced me to Mr. Gottschalk at the music house of G. Schirmer, No. 701 Broadway (1862) and later I called at his residence in Ninth Street, near Broadway.

Gottschalk was a man of splendid mentality, of an analytical turn of mind, a close observer, a clever reasoner and possessed of a keen sense of humor.

In South America In 1865 Gottschalk left San Francisco for South America and gave concerts in Lima and other large cities with great success, reaching Rio de Janeiro in 1869. He was entertained by the Emperor of Brazil, Don Pedro, and accorded other signal honors. On November 24 Gottschalk inaugurated a musical festival, assisted by 650 artists, and on the 26th, while seated at the piano playing his “Morte,” fell in a swoon. He lingered until December 18, 1869, aged forty years. His remains were cared for by the Philharmonic Society of Rio and later brought to the United States and interred in Greenwood Cemetery, where a magnificent monument marks his last resting place.

It is a large debt of gratitude that his native country owes to Louis Moreau Gottschalk, the first American musician to attain recognition abroad as an artist of real ability.

I have heard many of the great pianists, here and in Europe, and can conscientiously state that he was the equal of any in mastery of tone-color and technical equipment. He had fingers of steel and (as one writer expressed it) “paws of velvet.” Pianistic difficulties vanished under his magic touch. He was able to rouse his listeners to a state of frenzy or lull them to dreamy serenity. Paderewski, with his exquisite singing effects, and his ability to keep the melody clear and sustained, no matter how complicated or involved the elaborations, reminds me more of Gottschalk than any pianist I have heard. If Gottschalk had lived the usual span of life I doubt not that piano literature would have been enriched by works of merit and originality from his pen.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO