100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (227)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (227)

January 26, 1918

Page 5

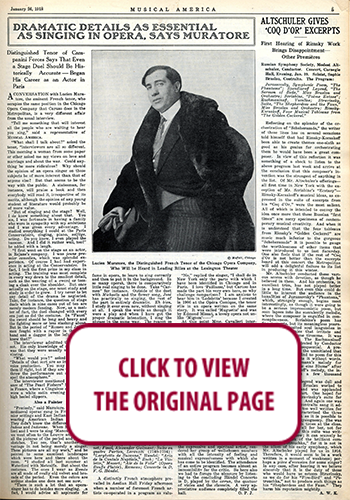

DRAMATIC DETAILS AS ESSENTIAL AS SINGING IN OPERA, SAYS MURATORE

Distinguished Tenor of Campanini Forces Says That Even a Stage Duel Should Be Historically Accurate—Began His Career as an Actor in Paris

A CONVERSATION with Lucien Muratore, the eminent French tenor, who occupies the same position in the Chicago Opera Company that Caruso does in the Metropolitan, is a very different affair from the usual interview.

“Tell me something that will interest all the people who are waiting to hear you sing,” said a representative of MUSICAL AMERICA.

“What shall I talk about?” asked the tenor, “interviewers are all so different. This morning a woman from some paper or other asked me my views on love and marriage and about the war. Could anything be more ridiculous? Why should the opinion of an opera singer on those subjects be of more interest than that of anyone else? But that seems to be the way with the public. A statesman, for instance, will praise a book and then everybody will read it, irrespective of its merits, although the opinion of any young student of literature would probably be of more value.

“But of singing and the stage? Well, I do know something about that. You see, I was fortunate in having a family who were in sympathy with my ambitions and I was given every advantage. I studied everything I could at the Paris Conservatoire, singing, piano, solfège, acting. Do you know, I even played the bassoon. And I did it rather well, too!” he added with a laugh.

“I first went on the stage as an actor, in Rejane’s company. I was jeune premier comedien, which was splendid experience. Of course I had had experience in acting at the Conservatoire. In fact, I took the first prize in my class in acting. The training was most complete in every way down to the smallest detail, such as the wearing of a sword or tossing a cloak over the shoulder. But once actually on the stage, one must study and study in order to grow. I try never to let any detail of the drama be neglected. Take, for instance, the question of stage duels which in nine cases out of ten are merely modern fencing. Now, as a matter of fact, the duel changed with every era just as did the costume. In “Faust” the sword should be long and heavy and the fighting more or less slashing about. But in the period of “Romeo and Juliet” men fought with a rapier in the right hand and a dagger in the left, did you know that?”

The interviewer admitted that he did not. His only knowledge of stage duels was that they were usually very unconvincing.

“What would you?” asked the tenor. “Details of that sort are as important as voice production. You may not notice them if right, but if they are wrong they throw the performance out of key and spoil the atmosphere.”

The interviewer mentioned a performance of “The Pearl Fishers” he had seen in France, where a Cingalese singing girl wore a white satin evening gown and high heeled slippers.

Also a Painter

“Precisely,” said Muratore. “I’ve seen mediaeval operas sung in François Premier settings and East Indian characters wearing American Indian moccasins. They didn’t know the difference between Indoue and Indienne. When Mme. Cavalieri and I were to sing ‘Manon’ in Paris, we went often to the Louvre and studied all the pictures of the period and I made sketches. You see, that’s another advantage in not being merely a singer. These pictures are all my work,” and he pointed to some excellent landscapes which were here and there about the room. “I studied all last summer at Waterford with Metcalfe. But about the costumes. The ones I wear as Romeo are all made of really old velvet and brocade of the period. Even the colors are antique shades one does not see now.

“There is such a lot that an opera-singer has to do besides mere singing. In fact, I would advise all aspirants for fame in opera, to learn to sing correctly and then to put it in the background. In so many operas, there is comparatively little real singing to be done. Take “Carmen” for instance. Outside of the duet with Michaëla and the flower song, José has practically no singing, the rest of the part is entirely dramatic. Eh bien, I study it over even now, without singing at all. I speak the words as though it were a play and when I have got the proper dramatic intonation, ·I sing the phrase in the same way. The reason so many singers have poor diction is because their production is poor. If your production is good, you never have to sacrifice a vowel for a tone.”

The interviewer saw a striking picture of Muratore as Canio lying on the desk. “Are you going to do ‘Pagliacci’ here?” he asked.

“No,” replied the singer, “I shall do in New York only the parts with which I have been identified in Chicago and in Paris. I love ‘Paillasse,’ but Caruso has made the part his very own here, so why challenge comparison? I am anxious to hear him in ‘Lodoletta’ because I created in 1906 at the Opéra Comique, the tenor role in an opera written on the same story. It was called ‘Muguette’ and was by Edmond Missat, a lovely opera not unlike ‘Mignon’”

At this point Mme. Cavalieri interrupted. “Mon Cher, Monsieur Chose est venu—”

“Ah! Then I must ask you to excuse me. You see, these first few days are such busy ones. But I hope your readers will be interested in our talk.” —JOHN ALAN HAUGHTON

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO