100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (274)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (274)

March 8, 1919

Page 13

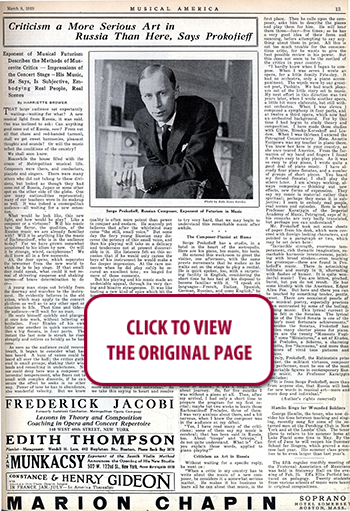

Criticism a More Serious Art in Russia Than Here, Says Prokofieff

Exponent of Musical Futurism Describes the Methods of Muscovite Critics—Impressions of the Concert Stage—His Music, He Says, Is Subjective, Embodying Real People, Real Scenes

By HARRIETTE BROWER

THAT large audience sat expectantly waiting—waiting for what? A new musical light from Russia, it was said. One was inclined to ask: Can anything good come out of Russia, now? From out all that chaos and red-handed turmoil, shall we get sweet harmonies, pleasant thoughts and sounds? Or will the music reflect the conditions of the country?

We shall soon know.

Meanwhile the house filled with the cream of Metropolitan musical life. Composers were there, and conductors, pianists and singers. There were many others who did not belong to these divisions, but looked as though they had come out of Russia, Japan or some other spot on the other side of the globe. One saw many nationalities represented; many of our teachers were in its makeup as well. It was indeed a cosmopolitan audience—all waiting for a new sensation.

What would he look like, this new light, and how would he play? Like a composer or a virtuoso? Will his music have the flavor, the qualities, of the Russian music we are already familiar with? Will it be anything like the music of Rachmaninoff, who is in the audience to-day? For we have grown somewhat accustomed to his idiom by now. Or will it be strange, weird, cacophonous? We shall know all in a few moments.

Ah, the door opens, which separates the newcomer from the new world to which he is to lay siege. If that small door could speak, what could it not reveal of shivering suspense and shaking nerves—of brave determination to do or—

A young man steps out briskly from the doorway and marches to the instrument. He evidently believes in the old axiom, which may apply to the concert platform as well as to any other spot or situation in life. That time and tide—the audience—will wait for no man. He seats himself quickly and plunges at once into work, without loitering or hesitation. Four Etudes of his own follow one another in quick succession; then a big Sonata, in four parts. The instant the last note is struck he rises abruptly and retires as briskly as he had come.

As soon as the audience could recover breath, it began to consider what had been heard. A buzz of voices could be heard all over the hall; the critics gathered in small groups, shaking their wise heads and consulting in undertones. No one could deny here was a composer of torrential temperament, who fears not to assail with complex discords, if he can secure the effect he seeks in no other way. Power of tone he has in abundance, also wonderful velocity. But we know quality is often more potent than power to conquer and enslave. He scarcely yet believes that after .the whirlwind may come “the still, small voice.” But some day the fiery young Russian may discover the potency of this small voice, and then his playing will take on a delicacy and tenderness not at present discoverable in it. His listeners felt on this occasion that if he would only caress the keys of his instrument he would make a far deeper impression. At the rare moments when he did play softly he secured an excellent tone; we longed for more of those moments.

But his playing and his music made an undeniable appeal, through its very daring and bizarre strangeness. It was like tasting a new kind of spice which bit the tongue. The tang was pungent, but not altogether unpleasant; one was not averse to tasting again, if only for the sake, of a new sensation. At least this audience thought so, for it remained to applaud and call for more, after the long all-Russian program was finished.

The critics departed to write wisely about “biceps,” “triceps,” “steel wrists” and the like. The conservatives decided it was all dreadful cacophony, and they resented having their eardrums assailed so mercilessly. Those with ears open to new ideas, new effects, sensational surprises, rather liked it all, and were willing to listen further—were open to conviction. They had faith to believe that future hearings would reveal excellences hidden on first acquaintance. For has not a professor from Petrograd said of this new light:

“It is from Serge Prokofieff that we can expect new words in musical art, more and more deep and individual.” So, we take this saying to heart and resolve to try very hard, that we may begin to understand this remarkable music after awhile.

The Composer -Pianist at Home

Serge Prokofieff has a studio in a hotel in the heart of the metropolis. Here are his piano, his music, his tools.

He entered this workroom to greet the visitor, one afternoon, with the same presto movements that he makes as he walks out on the stage to play a recital. He is quick spoken, too, with a surprising facility in English, considering the short time he has had at his disposal to become familiar with it. “I speak six languages—French, Italian, Spanish, German, Russian, and some English,” he asserted calmly, with his pleasant, broad smile, as though to know six tongues were the easiest thing in the world.

“Where did you acquire your piano technique?” he was asked.

“What is?”

“Your piano technique—how did you get it?”

“Oh, yes, I will tell you. There are some pianists who must practice many hours every day; again there are some who do not work very much—technique to them seems to be a gift of the gods. I think I must belong to the latter, for I do not need so much to practice. My fingers do not forget,” and he held up a wonderful hand, with long, supple fingers. Then the fiery young Russian took a few turns about the room, just through exuberance of energy, before settling down again in his chair.

“You see,” he continued “it took me some time to reach here after I left my home in Russia; it was a long, round-about journey. So, for five months I was without a piano at all. Then, after my arrival, I had only a short time to prepare the program for my first recital; maybe but two weeks to learn those Rachmaninoff Preludes, three of them. I was very anxious about them, and a bit nervous, when I knew the composer was in the audience at my debut.

“Yes, I have read many of the criticisms; some of them say my music is cerebral; that has been said in Russia too. About ‘biceps’ and ‘triceps,’ I do not quite understand. What is? ·Can you explain t hose words, applied to piano playing?”

Criticism an Art in Russia

Without waiting for a specific reply, he went on:

“When a critic in my country has to write about the music of a new composer, he considers it a somewhat serious matter. He makes it his business to learn all he can about that music, in the first place. Then he calls upon the composer, asks him to describe the pieces and play them for him. He will hear them three—four—five times; so he has a very good idea of their form and meaning, before attempting to say anything about them in print. All this is not too much trouble for the conscientious critic, for he wants to give the best possible review in his power. But this does not seem to be the method of the critics in your country.

“I hardly know when I began to compose. When I was seven I wrote an opera, for a little family Fête-day. It had no orchestra, only a piano accompaniment. The words were by our greatest poet, Pushkin: We had much pleasure out of the little story set to music. My next effort in this direction was two years later, when I wrote another opera, a little bit more elaborate, but still without orchestra. When I was eleven I composed a symphony in four parts, and at twelve a third opera, which now had an orchestral background. For by this time I had begun to study theory and composition. I have made those studies with Glière, Rimsky-Korsakoff and Liadow. When I was thirteen I entered the Petrograd Conservatory. Mme. Annette Essipowa was my teacher in piano there. You knew her here in your country, as she once toured America. From the formation of my hand and fingers I found it always easy to play piano. As it was so easy to play piano, I wrote quite a good deal of piano music. I have already four piano Sonatas, and a number of groups of short pieces. You heard my Second Sonata; I shall play the others later. I am always working, always composing—thinking out new effects, new forms of expression. They say my music is material rather than spiritual; perhaps they mean it is subjective; I seem to embody real people, real scenes and episodes. Here is what Professor Karatygin of the Imperial Academy of Music, Petrograd, says of it; his remarks are very badly translated, but perhaps you can understand.”

Mr. Prokofieff took out some sheets of paper from his desk, which were covered with foreign looking characters and pointed to a paragraph or two, which may be set down here:

“Invincible strength, enormous temperament, rich thematic imagination, remarkable harmonic inventiveness, painting with broad strokes—even touching the grotesque—these are found in Prokofieff’s music. There is astonishing boldness and energy in it, alternating with flashes of humor. It is quite wonderful music! You are bitten, pinched, burnt, but you do not revolt. He has some kinship with the American, Edgar Allen Poe. But here and there you can be touched by something_ tender, gentle, sweet. There are occasional pearls of fine musical poetry, especially precious when contrasted by some of the boiling, rushing music. This lyrical current is to be felt in the Sonatas. The lyrical theme of the Third Sonata is one of the author’s most fortunate achievements.”

Besides the Sonatas, Prokofieff has written many shorter pieces for piano. There are the twenty “Moments Fugitifs,” some “Miniatures,” a set of Etudes, some Preludes, a Scherzo, a charming Gavotte, five “Sarcasms,” and more than a score of vivid tone pictures and Dances.

Truly, Prokofieff, the Rubinstein prize-winner, the militant virtuoso, composer and performer, must be one of the most remarkable figures in contemporary Russian music. As Professor Karatygin concludes:

“It is from Serge Prokofieff, more than from anyone else, that Russia will look for new words in musical art—more and more deep and individual.” (Author’s rights reserved)

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO