100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (317)

100 YEARS AGO IN MUSICAL AMERICA (317)

December 13, 1919

Page 36

Recognizing Our Debt to Negro Music

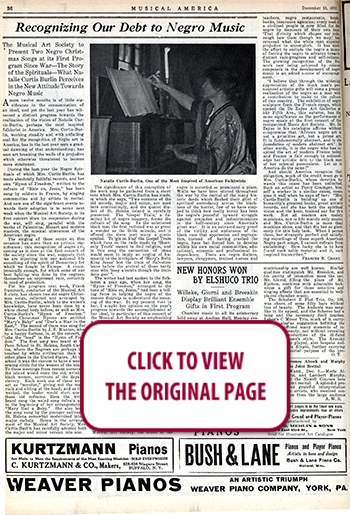

The Musical Art Society to Present Two Negro Christmas Songs at its First Program Since War—The Story of the Spirituals—What Natalie Curtis Burlin Perceives in the New Attitude Towards Negro Music

A MERE twelve months is of little significance in the consummation of an ideal, and yet the last year has witnessed a distinct progress towards the realization of the vision of Natalie Curtis-Burlin, perhaps the most inspired folklorist in America. Mrs. Curtis-Burlin, working steadily and with unfailing zeal for the recognition of Negro art in America, has in the last year seen a gradual dawning of that understanding; has seen art breaking the walls of a prejudice which otherwise threatened to become more straitened.

During the last, year the Negro Spirituals of which Mrs. Curtis-Burlin has made absolutely faithful records, and her own “Hymn of Freedom,” written to the refrain of “Ride on, Jesus,” has been sung by soldiers in France, by singing communities and by artists in recital. And now one of the significant events towards their adoption is to occur next week when the Musical Art Society, in its first concert since its suspension during the war, will sing, parallel with the works of Palestrina, Mozart and modern masters, the musical utterances of the American negro.

The singing of these songs on this occasion has more than an artistic significance; this recognition of negro art, coming as it does at the first concert of the society since the war, suggests that we are injecting into our national life something of the spirit of Democracy for which we fought in Europe. A cause, ironically enough, for which some of our best fighting was done by the negroes, themselves an oppressed race, certainly in need of protection.

For his program next week, Frank Damrosch, conductor of the Musical Art Scciety, has chosen two old negro Christmas songs, collected and arranged by Mrs. Curtis-Burlin, which to the writer’s knowledge, have never been done by a white choral body before, as well as Mrs. Curtis-Burlin’s “Hymn of Freedom.” These Christmas Hymns are entitled “Mary’s Baby” and “Dar’s a Star in the East.” The second of these was sung for Mrs. Curtis-Burlin by J. E. Blanton, who, by a happy fortune, is, at the concert, to take the “lead” in the “Hymn of Freedom.” The first song was heard at the Penn School in St. Helena, South Carolina, where the Negroes are perhaps less touched by white civilization than any other place in the United States. At this school it was the custom to have a weekly sewing circle for the women of the island. To these meetings from remote corners of the island would come the old, wrinkled black women, survivors of the days of slavery. Each week one of these would act as “monitor;” giving out the materials and sitting at the head; and as they worked, the leader would start one of these old refrains. Here the writer heard sung·the weird song refrain used in the beginning of her arrangement of “Mary Had a Baby.” She also heard the song sung by the younger natives of St. Helena somewhat modernized into a major melody. Hence in the arrangement of the Musical Art Society, Mrs. Curtis-Burlin has carefully adopted both the major and minor version into one.

The significance of this conception of the work may be gathered from a short note which Mrs. Curtis-Burlin has made, in which she says, “Two versions of the old melody, major and minor, are used here contrastingly, and the quaint dialect of St. Helena Island is carefully preserved. The ‘Gospel Train,’ a familiar bit of negro imagery, forms the refrain of the song. To the unlettered black man the first railroad was as·great a wonder as the Bible miracle, and it offered the slave poet many a poetic symbol. To ‘git on b’od’ the Gospel Train which runs on the rails made by ‘Heavenly Truth’ meant to find religion, and in this song the connection of ideas would seem to imply an urging of humanity to the birthplace of ‘Mary’s Baby King Jesus’ lest the train of Salvation leave before the arrival of those tardy ones who ‘keep a’comin though the train done gon.’”

The writer had last spoken to the folklorist a year ago, when her song, the “Hymn of Freedom,” arranged to the tune of “Ride on, Jesus,” had been a telling force in helping the negro of the remote districts to understand the meaning of the war. In my present visit to her, I sought her opinion on the year’s progress towards the accomplishment of her ideal, in particular of this concert of the Musical Art Society as emphasizing a recognition of the negro’s art.

“In the year which has elapsed since I last spoke to you on the subject,” said she, “I am more than ever convinced that the artistic utterance of the negro has a permanent significance, and is a lasting offering to our national culture.

“In an appreciation of that art lies one help toward a greater understanding of the negro; here is a basis of approach involving no controversy and no problem; music forms a bridge of sympathy that makes a greater friendship for the black man, instinctive and natural. I feel that Dr. Damrosch’s inclusion of these negro songs on his first program since the war has a certain human significance, a prophecy of true Democracy and of that greater justice which should be accorded those black men who fought in Europe for the rights of oppressed races and are asked to accept peaceably oppression at home. Those of us who have seen the bravery of the negro’s efforts towards self-development and self-respecting economic independence, cannot but rejoice that on so significant a program as this of the Musical Art Society, the music of the negro is accorded so prominent a place. While we have been stirred throughout the war by the recital of the many historic deeds which flashed their glint of spiritual ascendancy across the blackness of the horror, few of us have stopped to think how really heroic has been the negro’s peaceful upward struggle against prejudice and indiscrimination in the half-century since America’s great war. It is an extraordinary proof of the virility and endurance of the black race that oppression and segregation, instead of having crushed the negro, have but forced him to develop within his own racial communities, educational, economic and professional independence. There are negro doctors, lawyers, clergymen, trained nurses and teachers, negro restaurants, hotels, banks, insurance agencies; every need of a civilized people is now filled for the negro by members of their own race. ‘That divinity which shapes our ends, rough hew them though we may,’ has reversed what the white man expected prejudice to accomplish. It has made the effort to exclude the negro a means of forcing the negro to advance towards distinct race-progress and self-reliance. The growing recognition of the fine work now being achieved by colored composers in the development of negro music is an added source of encouragement.

“I believe that through the widening appreciation of the black man’s pronounced artistic gifts will come a greater realization of the negro as a man with a contribution to make to the culture of this country. The exhibition of negro sculpture from the French congo, which opened the De Zayas Art Galleries at 549 Fifth Ave., this autumn, has the same significance as the performance of negro music at the first concert of the reorganized Music Art Society. Mr. De Zayas in his catalogue affirms without compromise that ‘African negro art is not a primitive art, but a prime art. It is fundamentally abstract, and is the foundation of modern abstract art.’ In other words, it is the negro who has inspired the art of modern France today, and France is fair enough to acknowledge her artistic debt to the black men of her colonial possessions. Let us in America do the same!”

And should America recognize that obligation, much of the credit must go to Mrs. Curtis-Burlin, whose devotion towards this cause has been unlimited. Such an artist as Percy Grainger, himself a worker in a similar cause, measures it well when he says of her: “Mrs. Curtis-Burlin is building up one of humanity’s greatest books, great artistic records, and she has both the spiritual vision and the keen, trained ear for this work. Not all readers are mainly musicians, nor is life mainly only music; and Mrs. Curtis-Burlin is more than musician alone, and that fits her so gloriously for this holy task. When I peruse these, her strangely perfect and satisfying recordings of these superb American Negro part songs, I cannot refrain from exclaiming: How lucky she is to have found such noble material and it, such [an] inspired transcriber.” —FRANCES R. GRANT.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO