100 YEARS AGO ... IN MUSICAL AMERICA (15)

100 YEARS AGO ... IN MUSICAL AMERICA (15)

October 11, 1913

Page 2

MAGGIE TEYTE CORRECTS SOME FALSE IDEAS ABOUT DEBUSSY

French Composer "Most Misunderstood Man in Artistic Word," Declares Interpreter of His Works—Not a "Poseur, Dilettante and Iconoclast"—Music of His Songs So Expressive That Words Are Scarcely Needed—He Realizes Possibilities of His Present Style Are Exhausted

By MAGGIE TEYTE, October II, 1913

EDITOR' S NOTE—This article from the pen of Miss Teyte is unique in its interest in that the author is widely recognized as an interpreter of the works of the French composer. She has been for more than three years the pupil and intimate friend of Debussy and is frequently selected by him to give his songs their first hearing before the critical French public. Opinions of Debussy differ so widely and personal contact with him is so rare a privilege that Miss Teyte's authoritative statement may correct some misrepresentations.

CLAUDE DEBUSSY is probably the most misunderstood man in the artistic world to-day. Few can grasp the meaning of his music; even fewer can apprehend the significance of his character. He has been called a vain, affected poseur, a superficial dilettante, a self-constituted iconoclast with no intentions save to destroy; lacking in originality and with no more than an ordinary musical talent. In answering these opinions, let us discuss him first as a man and then as a musician.

I well remember my first meeting with Debussy. It was after I had been studying with Jean de Reszke long enough to be entrusted with the role of Mélisande at the Opéra Comique. Naturally I was a little frightened at the responsibility suddenly thrust upon me, for my predecessor had created the part and had made a great reputation in it. My fears were not lessened when I heard that the composer had sent for me to hold a consultation on the interpretation of the opera.

I went dutifully to the home of Debussy and waited in the studio with nervous eagerness. The master came in quickly and unceremoniously, a silent, diffident, bearded man. I must have looked like a schoolgirl, for I still wore my hair in braids. At any rate, Debussy looked at me sharply a nd then glanced around the room as though expecting to find someone else. Finally he again looked at me hard and then said abruptly, "Are you Miss Teyte?"

"Yes," I answered in a voice that did not seem to belong to me.

"Are you Miss Maggie Teyte?" he repeated.

"Yes," I answered again.

"But," he insisted, "Are you Miss Maggie Teyte of the Opéera Comique?"

"Yes," I answered for the third time.

He shook his head doubtfully, walked to the piano and began to play the music of the first act of "Pelléas et Mélisande." As soon as I began to sing, my nervousness disappeared. Before I had been singing ten minutes Debussy rose suddenly from the piano stool and rushed to the electric bell with the words: "Wait a moment. I must let my wife hear this!"

Mme. Debussy as Adviser

It was the greatest compliment that he could have paid me. For Mme. Debussy enters into everything' that her husband does, and he always considers her his necessary inspiration and support. I found later that he insisted on having her near him at all rehearsals and concerts in which he took part, and whenever she uttered an opinion or made a suggestion he accepted it with the greatest respect. Once an orchestra had to repeat a certain measure seven times during one rehearsal before both the composer and his wife were satisfied.

Debussy is always a severe critic of his own work as well as that of others. He expects perfection in every detail. If a singer cannot read his songs at sight and knows them thoroughly after one rehearsal he refuses to waste time in laborious study. He takes a perfect ear for granted, and counts upon finding his interpreter's intellect equal to his own. This may explain to some extent the fact that few singers have held the personal interest of Debussy for very long.

An incident occurs to me which exhibits Debussy's intolerance of all imperfection. A pianist of great reputation had been playing one of his compositions at a public concert, very well as it seemed to me. At the conclusion he obviously expected to be complimented by the composer, put Debussy was silent. Thereupon the pianist asked him point blank if he had been satisfied. Debussy merely answered that the interpretation was quite impossible, turned on his heel and walked away, leaving the performer crestfallen.

Chary of Curtain Calls

Such episodes as this have led to a popular impression that Debussy is unutterably conceited. Nothing could be further from the truth. Debussy's confidence in his work and in himself as a musician is unlimited, it is true, and this fact may at times lead to a suspicion of personal vanity. But as far as public approbation is concerned he is the most timid and retiring man imaginable. When I performed with him in Paris in concerts of his own works it was almost impossible for me to drag him before the footlights to respond to the applause of the audience. He would thrust himself far back into a corner of the wings and keep out of sight altogether if he could.

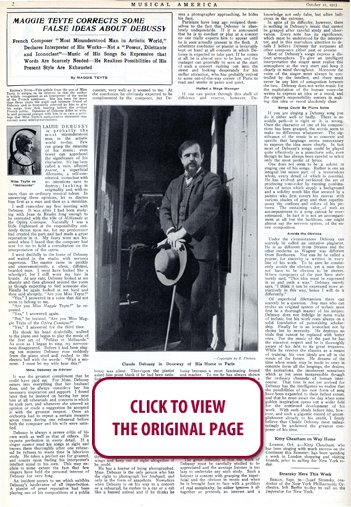

He has a horror of being photographed. Mme. Debussy is the only person who has the right to photograph her husband, and only in the form of snapshots. Nowadays when Debussy is on his way to a concert or a rehearsal, he rushes to a car or a cab like a hunted animal and if he thinks he sees a photographer approaching, he hides his face.

Parisians have long ago resigned themselves to the fact that Debussy is absolutely undependable. If it is announced that he is to conduct or play at a concert no one really expects him to appear until he is seen actually present in the flesh. A substitute conductor or pianist is invariably kept on hand at all concerts in which Debussy is expected to take part. If he comes at all, he is almost sure to be late, and the manager can generally be seen at the start of such a concert rushing out into the street and looking desperately for his stellar attraction, who has probably retired to some out-of-the-way corner of Paris to read and smoke in peace and quiet.

Halted a Stage Manager

If one can pierce through this shell of diffidence and reserve, however, Debussy becomes a most fascinating friend and teacher. To me he has always shown an almost parental kindness. Once at a rehearsal of "Pelléas et Mélisande" the stage manager insisted on correcting my interpretation of a certain part. No one knew that Debussy himself was present until suddenly his voice boomed forth from the back of the theater in a peremptory request that "Miss Teyte should be allowed to play the part as she liked, since he himself was entirely satisfied."

As a musician Debussy must be called a school in himself. He is the founder and head of the modern French School, it is true, but in my opinion the rest are merely weak imitators and no one has been found as yet to stand beside him. Because of his intense individuality he has been commonly misunderstood, but this is always the fate of a man who introduces a new style of art.

The great difficulty is that the work of Debussy must be carefully studied to be appreciated and the average listener is too lazy to undertake any such study. Such a listener is content with grasping the superficial and the obvious in music and when he is brought face to face with a problem of real complexity, he either ignores it altogether or pretends an interest and a knowledge not only false, but often ludicrous in the extreme.

In spite of its difficulty, however, there is nothing in Debussy's music that cannot be grasped after careful study and observation. Every note has its significance, which must be understood by the interpreter, and in this marvelous attention to details I believe Debussy far surpasses all other composers either past or present. Most of Debussy's songs express a distinct atmosphere. To give an intelligent interpretation the singer must realize this atmosphere at the very start and keep it clearly in mind throughout. Moreover the voice of the singer must always be controlled by the intellect, and there must never be any hint of antagonism between the two. Debussy does not write music for the exploitation of the human voice—he writes to express an idea or a mood, and the singer's responsibility centers in making this idea or mood absolutely clear.

Songs Could Be Piano Solos

If you are singing a Debussy song you do it either well or badly. There is no middle path—it is right or it is wrong. Once the character of one of his compositions has been grasped, the words seem to make no difference whatsoever. The significance of the music is so concrete and specific that language seems unnecessary to express the idea more clearly. In fact most of Debussy's songs could be played quite effectively as a pianoforte solo, even though he has always been careful to select only the most poetic of lyrics.

One does not seem to be a soloist in singing one of his songs. Rather is one an integral but minor part of a tremendous whole, every detail of which is essential. He has evolved and perfected the art of producing tone-color by running combinations of notes which supply a background and a solidity much like that secured by a painter who first covers his canvas with various shades of gray and then superimposes the outlines and colors of his pictures. The sustaining value of such an accompaniment to a song cannot be overestimated. In fact it is not an accompaniment at all but the backbone, one might almost say the nervous system, of the entire composition.

Avoids the Obvious

Under the circumstances Debussy can scarcely be called an imitative plagiarist. He is as different from Strauss and the other moderns as Wagner was different from Beethoven. Nor can he be called a poseur, for sincerity is written in every line of his work. To be sure he consistently avoids the obvious, yet a man does not have to be obvious to be sincere. Where composers of the past have stubbornly said, "This idea must be expressed in so and such a way," Debussy merely says, "I think it can be expressed more attractively in this way, hence I will do it differently."

Of superficial dilettantism there can scarcely be a question. Any man who can evolve an original system of technic must first be a thorough master of his subject. Debussy does not indulge in mere tricks of technic, but his work rests always on a solid foundation of painstaking scholarship. Finally he is an iconoclast not by choice but by necessity. He destroys no idols that cannot be replaced with better ones. For the music of the past he has the sincerest respect and he is thoroughly aware of his debt to its great treasures. While he reveres the classics as a means of training, his own ideals are all in the music of the future. He dreams of the time when music may be made to utter in concrete form all the longings, the desires the aspirations, the incoherent sensation, which as yet seem inexpressible through the ordinary channels of human intercourse. That time is not yet arrived for Debussy has the intelligence to realize that the possibilities of his new form of song have been expanded to their fullest extent, and that he must await the day when some golden inspiration opens out a wider field for the continued development of his work. With such ideals before him, however, and such a gigantic record of accomplishment already to his credit, I firmly believe that Claude Debussy must unhesitatingly be acclaimed the greatest composer of his time.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO