100 YEARS AGO ... IN MUSICAL AMERICA (30)

100 YEARS AGO ... IN MUSICAL AMERICA (30)

Janaury 10, 1914

Page 3

SUCCESS UNEQUIVOCAL CROWNS "L’AMORE DEI TRE RE" IN ITS FIRST AMERICAN PERFORMANCE

Coming Almost Unheralded, Montemezzi’s Opera Produces Electrifying Effect Upon Witnesses of Its Premiere at Metropolitan—“One of the Most Deeply Affecting and Full-blooded Scores Since Wagner”—Thrillingly Sung by Bori, Amato, Ferrari-Fontana and Didur

"L’AMORE DEI TRE RE” (“The Love of the Three Kings”), a three-act lyrical tragedy with text by the young but well-known Italian poet and dramatist, Sem Benelli, and music by the young but practically unknown Italian composer, Italo Montemezzi, was given for the first time in this country at the Metropolitan Opera House on Friday evening, January 2, as’ the second operatic novelty of the season. The production was consummated with a minimum of advance heralding, without increase in the prices of accommodations and without any particular claims of the management in respect to the artistic qualities of the work. And the wisdom of this policy of comparative silence and seeming indifference was demonstrated forcibly and movingly at the première even as had been the case with “Boris” last season and with “Konigskinder” two years earlier.

“L’Amore dei Tre Re” is in relation to the “Rosenkavalier” a repetition of the case of “Konigskinder” and the “Girl”—only with a reversal of nationality in the present instance. Gently and unostentatiously it unfolded itself a creation of the purest, most touching, simplest and most resistless beauty, a pregnant new word in the lexicon of modern Italian opera, in many ways the most gratifying example of musical drama from the higher aesthetic standpoints that has come out of Italy since Verdi.

True enough, the drama as such is very far removed from the coarse, sensuous, blood-heating affairs so highly prized by contemporary operatic artisans of that country and so dear, though vitiating, to popular taste. True, as well, Montemezzi has neither essayed nor achieved fire-eyed and revolutionary conclusions in his music for the delectation of progressive pedantry. Nor yet has he pandered, Puccini-like, to obvious musical appetites. In spite of all these impediments, apparently formidable to those of superficial mentality, there need be little apprehension respecting the success of “L’Amore.” Popular psychology in such matters often seems baffling to those who fail to recognize that the great body of the public is in the last analysis fully responsive to the effects of the genuinely sterling in art. Lofty beauty paired with sincerity is an element to which the popular consciousness eventually reacts despite the controversions of cynicism. And with these qualities Montemezzi’s opera is suffused from the first bar to the last. Moreover it has the invaluable asset of brevity; barely two hours and a half are required for the enactment of the tragedy, including the two intermissions, thus bringing it practically within the same time limit as “Bohème.”

In this brief preamble momentary reference must likewise be made to the magnificently opulent mounting provided by the Metropolitan, and the devoted efforts and superb interpretation accorded the work by Miss Bori, and Messrs. Amato, Edoardo Ferrari-Fontana and Didur, not forgetting the all-comprehensive influence of Mr. Toscanini at the orchestral helm.

Success Unequivocal

Success indeed crowned the new opera absolutely and unequivocally and it may forthwith be considered to have taken its place in the Metropolitan repertoire as a popular favorite destined to rank with “Boris” and “Konigskinder.” The first act, to be sure, left the issue unsettled, for though the large audience applauded it cordially it was not yet prepared to pledge its faith unreservedly. But doubt and hesitancy vanished with the second act, after the thrilling conclusion of which the house broke into a tornado of applause and hypothetical success became assured triumph. Sixteen times were the four principals summoned before the curtain amidst cheers, and unavailing efforts were made to bring forward Mr. Toscanini. But the conductor, later reported to be indisposed, refrained from appearing. Practically everyone remained to witness the tragic dénouement and there was also much enthusiasm when the final curtain fell.

The production was in all its departments worthy of the little master-work. The mise-en-scene by Mario Sala is striking in every scene—the sombre hall with its huge blocks of marble supported by thick marble columns; the castellated battlements’ in the second act with massive fortress in the background and overhead, floating clouds which thicken at the approach of the catastrophe; and. the chapel crypt in the third, a reproduction of the church of San Vitale in Ravenna with its architecture and mosaics of Byzantine style.

Dramatically the four leading artists played into each other’s hands in unsurpassable style. Lucrezia Bori, as Fiora, put to her credit the best achievement of her American career. A ravishing picture to the eye, a marvel of grace and plasticity, she sang enchantingly and denoted with a world of pathos the soul-struggle of the young woman fully conscious of the worth of her lord, touched by the infinite pathos of his idolatry of her, yet powerless to resist the importunities of one whose ardor overrides all her scruples. Her Fiora heightens the young woman’s artistic stature very noticeably.

Ferrari-Fontana’s Début

Mr. Ferrari-Fontana—the husband of Mme. Matzenauer—who had never before been heard -in New York, won an instantaneous place in the affections of his audience by his work as Avito. He acted it intelligently and revealed a tenor voice of great volume, essentially Italian in timbre but always virile, ringing and resonant and well-handled. Nervousness may have had something to do with the unsteadiness of his tones at the beginning of the opera, for this disappeared as the evening advanced. His further appearances will be expectantly awaited.

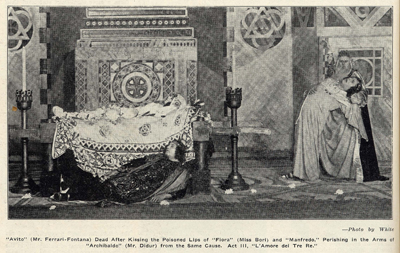

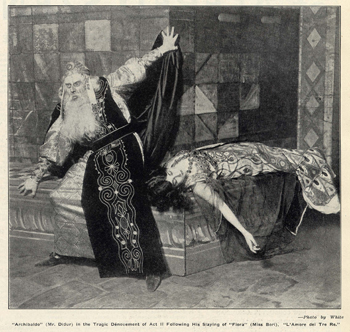

Mr. Ferrari-Fontana—the husband of Mme. Matzenauer—who had never before been heard -in New York, won an instantaneous place in the affections of his audience by his work as Avito. He acted it intelligently and revealed a tenor voice of great volume, essentially Italian in timbre but always virile, ringing and resonant and well-handled. Nervousness may have had something to do with the unsteadiness of his tones at the beginning of the opera, for this disappeared as the evening advanced. His further appearances will be expectantly awaited.In notably good voice, Mr. Amato also covered himself with glory as .the noble-hearted, all-forgiving Manfredo, the most sympathetic figure in the work. He sang his farewell to Fiora with due feeling for its tenderness and was moving in the death scene. Mr. Didur has done nothing better outside of Boris than the blind Archibaldo, prescient in his world of darkness, goaded to madness by the thought of his son’s betrayal and eventually, through the supreme irony of fate, bereft of all that .made life tolerable for him. The strangling of Fiora he made properly gruesome and he looked the embodiment of fate as, with halting steps but firm determination, he carried away the body of his son’s wife whom he had loved with jealous affection. Mr. Didur, moreover, sang the music well. Mr. Bada filled the small râle of the guard, Flaminio, adequately while Mr. Audisio, Mme. Maubourg and Mme. Duchène assumed rôles of very subsidiary account. The mourning choruses were beautifully sung.

Despite his reported illness Mr. Toscanini read this score with overwhelming dramatic force and also with a wealth of poetic tenderness. There were moments, though, in which he permitted his enthusiasm for the instrumental parts to militate against discretion with the inevitable consequence of engulfing the singers. The orchestral execution left no flaw open to critical attack.

The Tragedy of Benelli

A detailed summary of the argument of Sem Benelli’s drama having been given in last week’s issue of MUSICAL AMERICA, the need is obviated of its reiteration at this writing. Suffice it to recall that its scene is a feudal castle in a mountainous region of Italy, its time of action some indeterminate period of the middle ages forty years after an unnamed barbarian invasion. Briefly, the essentials of the plot treat of the illicit passion of Fiora, spouse of the warrior Manfredo, for Avito, an Italian princeling subjugated by the ruling invaders—among whom Manfredo and his blind and aged father, Archibaldo, are leaders—of the surprisal of the guilty pair by the latter, who straightway avenges his son’s honor by strangling the girl and then entraps his son’s betrayer by the device of poison spread on the dead Fiora’s lips. But Archibaldo further becomes party to his own unhappiness by unwittingly causing the death of the guiltless Manfredo who likewise kisses the lips of his wife as she lies on her bier.

In its operatic form Sem Benelli’s tragedy has been subjected to practically no alterations beyond a slight abridgement of several speeches and a few unimportant changes of words made necessary by musical exigencies. The poet has converted the episodes which originally preceded the entrance of Avito in the last act to elegiac choruses on the stage and behind the scenes. Beyond that the drama remains intact. With the possible exception of. Brian Hooker’s “Mona” no such beautiful libretto has fallen to the lot of an opera composer in many years and certainly none of Italian extraction has been so exceptionally favored. In matter and treatment Benelli’s piece betrays something of a kinship to Maeterlinck—the Maeterlinck of “Monna Vanna”—and d’Annunzio. Admirably proportioned, wrought with compelling emotional power, dramatic logic and consistency, simple in motive, it is always atmospheric and poetic. The sense of impending tragedy is established from the outset.

Though a perusal of the libretto conveys an impression of possible slowness and paucity of action the idea completely vanishes in the course of actual representation. As in “Tristan,” however, the action is preeminently psychologic.

It may be urged that the tristful tale offers no feature of novelty, that it is but a variant of “Francesca da Rimini” and similar in its essentials to countless others of that stamp. The contention is undoubtedly valid but how vain! Whether familiar in its fundamental aspects or not it is in the profoundest measure elemental and human, a story a thousand times repeated in this guise or in that, but never old. Benelli’s personages, too, are clearly drawn, and admirably vitalized figures—notably the blameless, large-hearted, all-forgiving Manfredo, innocent victim of an inexorable fate, and the blind Archibaldo, a sort of Guido Malatesta, stern and terrible arbiter of savage justice, a patriarchal Nemesis, at once awesome and pathetic. Four characters sustain the burden of the drama—the chorus is a picturesque but none the less an episodic element in the last act—yet not for one moment does interest flag. The emotional plan is not of the nerve-rasping order favored by the disciples of the younger Italian school. It is that of tragedy in the lofty Aristotelian sense.

Benelli is a true poet (how unutterably of another world is this text from the concoctions of that clever hack Illica!) and “L’ Amore” is in almost every line redolent of the grace of imagination and the beauty .of tender poetic fancy. Its verse is pliant and elastic. Unlike Hooker’s poem for “Mona,” it is not of such concentrated richness of expression and imagery as to defy the enhancement of its eloquence by musical investiture. In divining the ideal suitability to operatic purposes of .a work of this nature and in adapting it to such in barefaced defiance of all the tenets of Italian veritism, Italo Montemezzi steps forth without warning into the front rank of contemporary operatic writers, one who if he continues to travel the path which he has trodden in “L’Amore dei Tre Re” will prove himself an untold artistic boon to his country by restoring its opera to the sphere of poetry, nobility and dignity from which “realists” have sought in an evil day to divorce it.

In the process of a critical summary it becomes necessary to estimate the new work on the respective basis of poem and score. Nevertheless, the hearer of the opera must be forcibly struck by the extraordinarily felicitous amalgamation of these two factors, their rare unity and ideal coherence.

Montemezzi’s Genius Indubitable

Montemezzi is but twenty-eight years of age. In his present score—his third operatic venture, the previous ones having been “Giovanni Gallurese” and “Hellera”—he has well-nigh managed in three or four instances to touch greatness. But if “L’Amore” is big in intrinsic virtues it is bigger still in promise. The young man possesses indubitable genius. In some respects he is already a master. To what heights his bounteous innate gifts will ultimately conduct him can scarcely be surmised at this juncture. Normal advance along the lines indicated by the present score may prove him the legitimate heir to the supremacy of Verdi.

The grasp of the principles of operatic technic and craftsmanship is consummate. Montemezzi’s sense of the dramatic is innate and compelling. He comprehends in the fullest the relative functions and capacities of orchestra and voice and writes for the latter with unerring instinct for what is idiomatic and most effective in the best modern sense. No explosive effects nor awkward infractions of the melodic line—so prevalent in contemporary operatic writing—are discernible in this fluent and supple, arioso, veritable type of Wagnerian “speech-song,” magnificent in the extensive reach and broad span of its melodic phrases.

The grasp of the principles of operatic technic and craftsmanship is consummate. Montemezzi’s sense of the dramatic is innate and compelling. He comprehends in the fullest the relative functions and capacities of orchestra and voice and writes for the latter with unerring instinct for what is idiomatic and most effective in the best modern sense. No explosive effects nor awkward infractions of the melodic line—so prevalent in contemporary operatic writing—are discernible in this fluent and supple, arioso, veritable type of Wagnerian “speech-song,” magnificent in the extensive reach and broad span of its melodic phrases.Viewed in its larger aspects Montemezzi’s score discloses itself as one of the most deeply affecting, whole-heartedly sincere, virile, full-blooded and emotionally persuasive that has come to light since the death of Wagner. From the very outset the young composer summarily evinces his absolute independence of Puccini. A Wagnerian influence is, doubtless, inherent in its substance even as it permeates all modern composition to a greater or lesser extent, but Montemczzi is neither a servile copyist nor yet an unmitigated epigone.

A few chord formations savor vaguely of Debussy and a tinge of Russianism is sensed at moments—a touch of the Tschaikowsky of the “Manfred” Symphony, implied but not directly expressed and filtered, moreover, through the mask of the young composer’s own pronounced musical personality. Already his individuality is patent and his speech perceptibly his very own. Invariably modern in spirit his music is guiltless of grotesque harmonic or orchestral aberrations. But its physiognomy is recognizably characteristic.

Prodigality of means is generally a failing consonant with youth in the sphere of musical creativity. But Montemezzi, in this splendidly concise and symmetrical score, never oversteps the bounds of modesty. His orchestral requisitions are not excessive and his scoring is comparatively light. Yet how translucent, how rich in color, how plastic, how amply compact and massive in moments of climax! Indeed, there is probably no living Italian musician who can boast a more comprehensive technic, more solid musicianship or greater facility of creating atmosphere with a few simple strokes.

Melodic Invention

Montemezzi’s vein of melodic invention at once plenteous and opulent. Not a commonplace nor banal phrase defaces “L’Amore” for the composer’s thought is at all times distinguished, poetic, refined. For all its modernity of feeling an intangible element of classicism pervades the score. Intense, impassioned, it is yet music that never transgresses the canons of fundamental artistic continence and lofty beauty.

To a certain extent the score of “L’Amore” is contrapuntal and in such cases it becomes a golden web of polyphony, each strand and fiber of which glitters and sparkles discernibly. It is emphatically polyphony which “sounds,” to use a musician’s term. Strong and varied rhythmic accents employed solely or else traversing each other’s path in counter motion impart zest and frequently deep dramatic significance. Leading motives are traceable to the number of five or six but they undergo no appreciable symphonic germination nor form the warp and woof of the music in Wagnerian fashion. Always they are simple and readily recognizable upon recurrence—as in the case of the stumbling, disjointed, rhythmically broken pizzicato figure denoting the blind Archibaldo. This theme quickly resolves itself into a sinister, menacing musical symbol of portentous, fateful import. Likewise one finds apposite tonal exemplifications of Manfredo’s deep-felt conjugal love, of the tramp of his horses—a dull insistent rhythmic thud that association quickly informs with terrific meaning-and another for the passion of Fiora and Avito. Vain painting of externals is non-existent. The music is introspective in the main, and when not employed to the ends of pure subjectivity it serves to establish the requisite atmosphere of the scene. With overpowering effect it depicts the awful suspense and tragic horror of the closing part in the second act—the climactic one of the opera.

To a certain extent the score of “L’Amore” is contrapuntal and in such cases it becomes a golden web of polyphony, each strand and fiber of which glitters and sparkles discernibly. It is emphatically polyphony which “sounds,” to use a musician’s term. Strong and varied rhythmic accents employed solely or else traversing each other’s path in counter motion impart zest and frequently deep dramatic significance. Leading motives are traceable to the number of five or six but they undergo no appreciable symphonic germination nor form the warp and woof of the music in Wagnerian fashion. Always they are simple and readily recognizable upon recurrence—as in the case of the stumbling, disjointed, rhythmically broken pizzicato figure denoting the blind Archibaldo. This theme quickly resolves itself into a sinister, menacing musical symbol of portentous, fateful import. Likewise one finds apposite tonal exemplifications of Manfredo’s deep-felt conjugal love, of the tramp of his horses—a dull insistent rhythmic thud that association quickly informs with terrific meaning-and another for the passion of Fiora and Avito. Vain painting of externals is non-existent. The music is introspective in the main, and when not employed to the ends of pure subjectivity it serves to establish the requisite atmosphere of the scene. With overpowering effect it depicts the awful suspense and tragic horror of the closing part in the second act—the climactic one of the opera.Montemezzi does not resort to concerted numbers or detachable pieces. From beginning to end the music is closely concatenated. Separate episodes do, however, stand forth by virtue of their sheer beauty and dramatic eloquence-as the blind man’s superb narrative in the first act, the tremendous, foreboding orchestral interlude as Fiora, in fearful perturbation, mounts the battlements, the impassioned, glowing duo of the lovers, and, in the third act, the impressive choruses of a Gregorian cast sung off-stage a capella, as a requiem to the dead princess. Musically and dramatically the second act is the choicest of the three with the third a close second. In the latter Montemezzi has voiced the heart-broken lamentations of Avito in music of tear-compelling poignancy. HERBERT F. PEYSER.

Comments of other New York critics on the première:

The first hearing of this work prompts the opinion that it is one of the strongest and most original operatic productions that have come out of Italy since Verdi laid down his pen. —Richard Aldrich in The Times.

I can only say that in looking back over Italian opera since Mascagni’s “Cavalleria” I have not noted the distinct promise of genius so unmistakably in anything as in Montemezzi’s “Love of Three Kings.” —Maurice Halperson in the Staats Zeitung.

The most significant quality of the work is its freedom from the domination of the style now the most popular in Italian opera. Montemezzi has boldly rejected the idol Puccini. He has chosen his own methods and elected to appeal to the world with an art almost aristocratic in its manner, certainly seeking for nobility of line and purity of color, and yet as capable of delineating passion as the classic verse of Euripides. —W. J. Henderson in The Sun.

It is a beautiful score, free from earsplitting dissonances yet vitally dramatic. It is not reminiscent of any composer; least of all does it resemble any of the musical products of modern Italy. Mr. Montemezzi is not afraid to write melody, for in the various love scenes long phrases of melodic beauty fairly purl from his pen. —Edward Ziegler in The Herald.

The composer has provided nothing strikingly original in his music, yet it has individuality. There are evidences of Verdi in his later composing period, of Wagner and even of Debussy. The principal elements to commend are the admirable technical construction, appropriate orchestral color , and the directness with which Montemezzi invariably proceeds. —Pierre V. R. Key in The World.

Musically, Montemezzi’s opera made even a better impression than it seems to have done at its first success in Italy last year. —W. B. Chase in The Evening Sun.

Italo Montemezzi was a name that meant nothing to most of us yesterday. To-day it will be on the lips of every music lover, for his opera, “L’Amore Dei Tre Re,” is a work of genius. —Sylvester Rawling in The Evening World.

A work of power and vitality, a work that breathes the spirit of sincerity and throbs from beginning to end with human passion, reaching in the second act a climax of dramatic power, of scorching emotional intensity, that seems almost without precedent on the lyric stage. —Max Smith in The Press.

In short, it was abundantly evident that the Metropolitan had secured an opera by a new composer which is a complete success, both with the cognoscenti and with the general public. —H. E. Krehbiel in The Tribune.

COMPOSERS AT “BOHEMIANS”

Unique Organization of Musicians Has Hearing of Creative Artists

Unique Organization of Musicians Has Hearing of Creative Artists

“The Bohemians” gave their first “Composers’ Evening” of the present season on Monday evening, January 5, at Lüchow’s, before a large gathering of members of this unique organization. On this occasion the works heard were Edmund Severn’s suite for violin and piano “From Old New England,” in which this eminent American musician has shown his splendid creative gift and musicianship in working up some traditional New England tunes in serious and harmonically individual manner. The suite was finely played by Maximilian Pilzel, violinist, and Frank Bibb, pianist. A group of four songs, “Die Ablosung,” “A Nocturne,” “Come to Me” and “A Litany,” by A. Walter Kramer, were sung in an admirable manner by William Simmons, the young baritone, with the composer at the piano.

Leo Schulz, the popular ‘cellist, played his own melodious Reverie in his best style, ably assisted by Albert von Doenhoff at the piano . Finally there were heard three songs by Dr. Nicholas J. Elsenheimer, sung by Edmund A. Jahn, bass, with the composer as accompanist. The songs, “Die Geister am Mummelsee,” “Ein Fichtenbaum steht einsam” and “Sie will tanzen, tanzen will das Meer” won marked approval from the members of the club, being songs of decided value and seriously conceived. The evening proved an enjoyable one, reflecting great credit on the new secretary, Clarence Adler, who took complete charge of the arrangements.

CLARA BUTT BESET BY STRIKERS

Contralto and Her Husband Find Auckland in State of Siege

Contralto and Her Husband Find Auckland in State of Siege

Mme. Clara Butt and Kennerley Rumford, who are now completing their second Australasian tour, had rather an unpleasant experience in New Zealand, for their successful tour was interrupted by the great shipping strike. The singers had just completed their South Island tour in Christchurch, when all the water side workers came out on strike, and Mme. Butt and Mr. Rumford were unable to leave Christchurch, as no boats were sailing from the port to Wellington. They had to remain in Christchurch for a week, and their sold-out concerts in the North Island towns had to be abandoned, but eventually they continued their tour. They found Auckland in a state of siege. No spirituous liquors were being served, as it was feared that the strikers would get unmanageable. No tram cars were running and many of the citizens protected themselves with firearms. The singers gave their concerts in Auckland just the same, and the attendance was quite as large as if the conditions had been normal. Having concluded their New Zealand tour Mme. Butt and Mr. Rumford met with another setback, being unable to sail from Auckland to Sydney, as the steamer due to leave that port was taken off. They had to journey right down the island again to Wellington, where they eventually sailed for Australia. They sail for America by the Tahiti from Sydney on December 27 and are due to open their second American tour in San Francisco toward the end of January.

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO