Reviews

Kosky's New Rheingold: Exploiting the Environment and So Much More

LONDON—There’s little doubt that the first installment of Barrie Kosky’s new Ring Cycle for the Royal Opera House was the hottest ticket of the London season. At this September 12 premiere performance of Das Rheingold, the Australian director unveiled a clear-sighted, visually rich staging with environmental issues firmly at its heart.

LONDON—There’s little doubt that the first installment of Barrie Kosky’s new Ring Cycle for the Royal Opera House was the hottest ticket of the London season. At this September 12 premiere performance of Das Rheingold, the Australian director unveiled a clear-sighted, visually rich staging with environmental issues firmly at its heart.

In a program note, Kosky described his 2009 Ring for Staatsoper Hannover as a “trainwreck production”—a “patchwork quilt of ideas” than never quite cohered. He has, however, taken one striking image from it, reprising his depiction of the earth goddess Erda as a naked, elderly woman, who at one point walks toward Wotan and offers him comfort. In this new staging, Kosky goes a step further, placing Erda front and center, telling the story through her eyes as if in a series of painful reminiscences.

The curtain rises on Rufus Didwiszus’s concrete-framed set, its only feature an enormous, charred log. These are the smoking remains of the mythical world ash tree, despoiled by Wotan when he ripped away a branch to gain its power and fashion his spear. As Kosky rightly observes, in this world decay set in well before the action of the opera. Alberich’s later theft of the gold, here transformed into a greasy yellow sludge that oozes from one of the tree’s open wounds, only serves to accelerate a natural disaster that started long ago.

Erda opens the show, crossing the stage in silence, her shuffling gait a painful reminder to anyone familiar with dementia sufferers. It was a tour-de-force performance by Rose Knox-Peebles, the 82-year-old actor and model who made a similarly haunting appearance in Todd Field’s Tár. Weary and lost, she turns, covers her eyes, and begins to dream her dream. Only then does Wagner’s prelude begin its irresistible surge and swirl.

Later, to emphasize her subjugation, she appears as a grey-uniformed servant, glumly watching the gods as they plot and plan. The most terrifying image is reserved for the Nibelheim scene, where Alberich has strapped the writhing woman to the fallen tree, hooking her up to a fiendish milking machine that is sucking the golden slurry from her withered breasts.

Costumes (Victoria Behr) are generally modern. Only a tweedy Wotan and Fricka pays homage to an Edwardian past of shooting parties and picnics. The Rhinemaidens—Katharina Konradi, Niamh O'Sullivan, and Marvic Monreal, all excellent —are fishnet-clad vamps, the giants, sharp-suited and tattooed wheeler-dealers. Loge, too, is a slick operator, with twinkle toes and a mercurial line in maniacal laughter.

An altered universe

Christopher Maltman (Wotan), Sen Panikkar (Loge) in Das Rheingold at the Royal Opera House

There are plenty of things the traditionalist might miss: the water in this Rhine has long gone; there is no Valhalla (despite copious plans, it seems to remain a pipe dream); there is no dragon, just a partially obscured golden goblin; no toad, and no sword. The hoard consists of buckets of yellow slime, which Alberich appears to find oddly tasty. To pay off the giants (who are of normal stature), poor Freia—a fiery, bright-toned Kiandra Howarth—has to lie bravely in an old tin wheelbarrow and have bucket-loads of golden gloop poured over her. The rainbow bridge is fabulous, a downpour of multicolored shiny ribbons that draws the capricious eyes of these self-indulgent gods. Alessandro Carletti’s magical lighting is a marvel throughout.

Kosky has a keen sense of humor, but he never allows moments of silliness to spill over into the kind of senseless farce that bedeviled Richard Jones’s staging of the same opera last year for English National Opera (that production, by the way, once destined for the Met, now appears on hold, a victim of Arts Council England’s draconian cuts to the ENO budget). Kosky’s are characters we can believe in and often empathize with.

Antonio Pappano did an outstanding job in the pit, embodying the score with spot-on tempi and creating a convincing musical narrative that was grand when it needed to be, yet contained pockets of chamber-like intimacy—Loge’s cynical description of women’s charms was an oasis of loveliness. His orchestra was first-class, the brass exceptionally full and warm. Occasionally there were timing issues between orchestra and stage, but these should be easily righted.

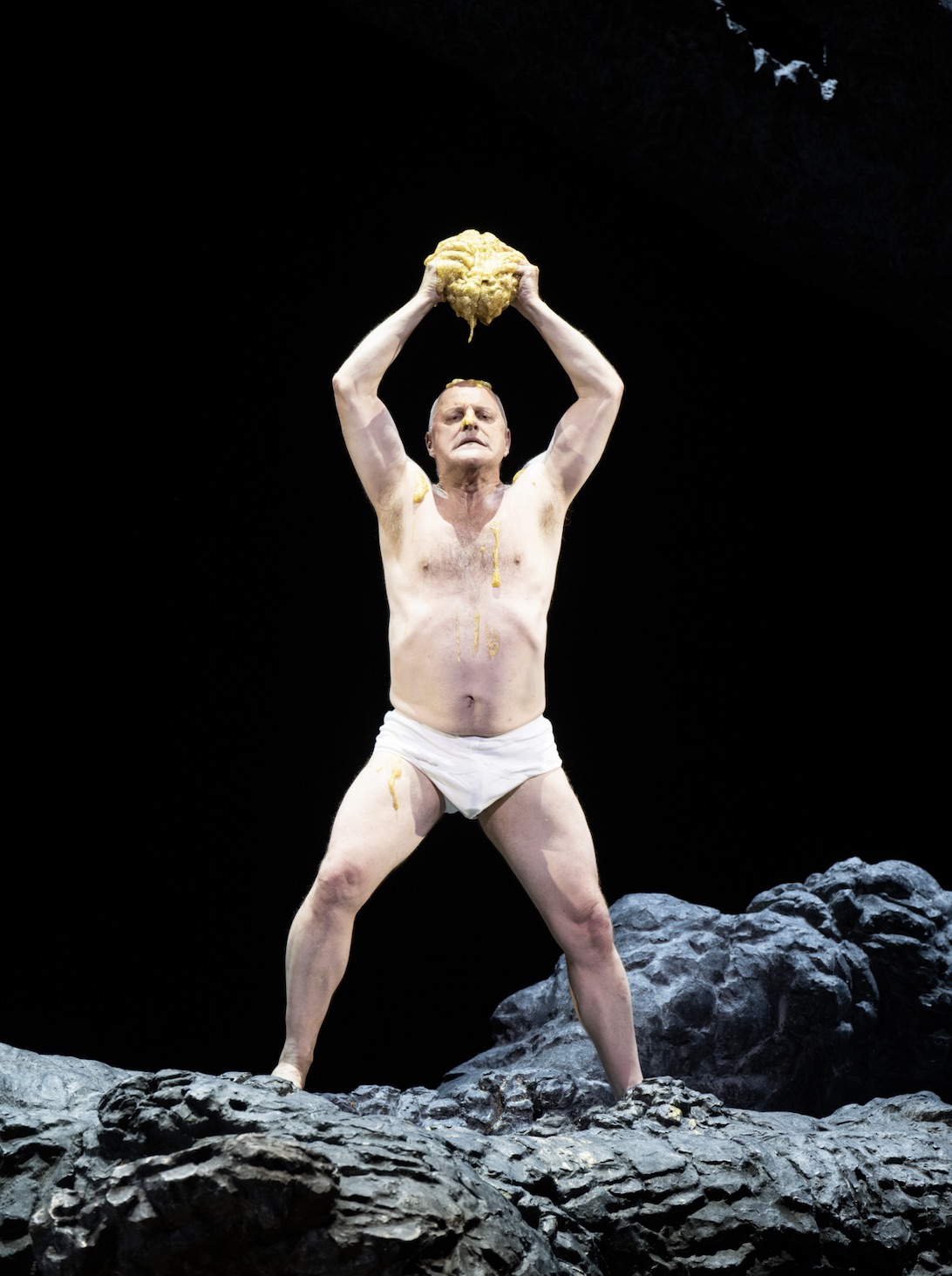

Rose Knox-Peeble (Erda), Christopher Purves (Alberich), Sean Panikkar (Loge)

As for the cast, it was mostly excellent. British baritone Christopher Maltman has been moving up a size in the voice department in recent years and his ringing Wotan was truly sumptuous of tone. Not only was it a beautifully sung account, he got to the nitty gritty of the text with unerring acuity. An interview suggested he’d been coached by John Tomlinson. If so, it showed. He was neatly paired with Sean Panikkar’s attractively sung Loge, again, a vocal actor using words and meaning to create an intricate account of the shapeshifting fire god.

On paper, Christopher Purves should have made a blistering Alberich. Frustratingly, the top notes are no longer secure—a few were missing altogether—and he compensated by sometimes acting too hard. Nevertheless, it was a notable performance. Humiliated by the Rhinemaidens—Kosky at one point had them whip out his (presumably) fake genitalia—he stole the treasure by appearing to tear Erda’s golden brain from out of her skull.

Among the rest of the cast, Marina Prudenskaya was vocally and dramatically fussy as Fricka. Kostas Smoriginas’s Donner was virile, if a little tight of voice, and Rodrick Dixon was a little reedy for Froh. Insung Sim and Soloman Howard, however, were formidable as Fasolt and Fafner. Howard, a true bass, was especially fearsome battering his brother to death before ripping away the ring.

Although it would be easy to label Kosky’s Rheingold as an environmental flag waver, there’s a lot more here as well, including humanity’s ability to exploit each other while casually despoiling the planet. Smart and thought-provoking, it left me eager to find out where the director is headed next.

Top: Christopher Purves (Alberich)

Photos by Monika Rittershaus

Classical music coverage on Musical America is supported in part by a grant from the Rubin Institute for Music Criticism, the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and the Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation. Musical America makes all editorial decisions.

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO