Reviews

Champion: Dressed for Success

Success was all but assured at the Metropolitan Opera debut of the opera Champion before the curtain went up.

The story of middle-weight boxer Emile Griffith (1938 – 2013) has triumph, tragedy, and extra texture that comes with repressed pre-Stonewall gay sexuality. The Met and composer Terence Blanchard have been building good will over the past year with the precedent of Blanchard’s Fire Shut up in My Bones last season and the current promotional photos of Champion star bass-baritone Ryan Speedo Green dressed down in boxing shorts. The message is clear: The Met is open to everyone, especially since the company has seats as low as $32.50 with a mere $2.50 service charge. And by the end of the Monday opening, the audience (middle-age, diverse) appeared thrilled.

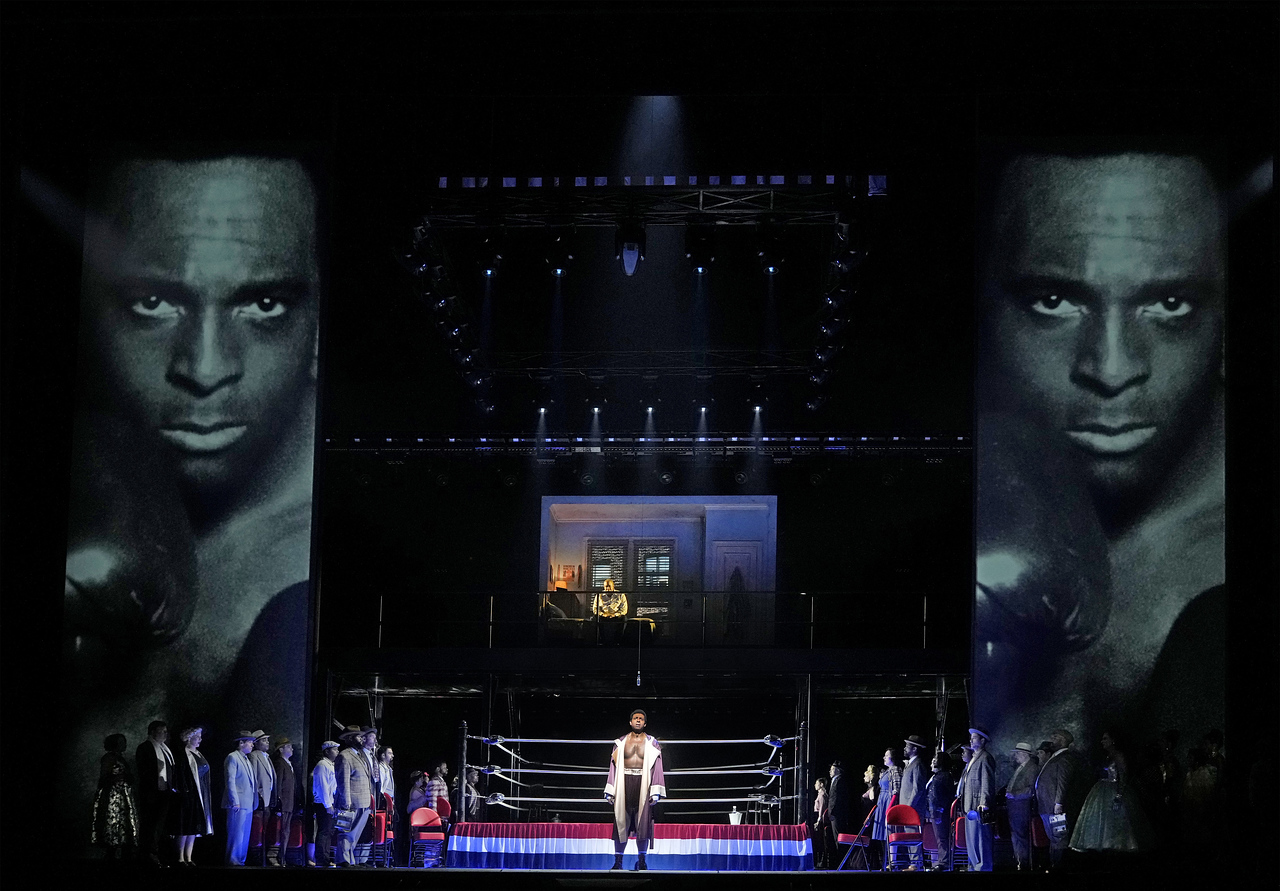

The opening Carnival scene in the Met's new production of Champion

The total package is highly attractive; cast (Eric Owens, Latonia Moore, Ethan Joseph, plus Speedo), direction (James Robinson), and choreography (Camille A. Brown) create a rich, provocative theatrical experience encompassing social issues but never at the expense of a good show. The two-tier set by Allen Moyer and projections by Greg Emetaz opens the proceedings with a Caribbean carnival that leads, inevitably, to the most credible onstage boxing ring since Broadway’s short-lived Rocky - the Musical. Blanchard’s music is more jazz and blues inflected, has greater originality and higher highs than Fire. An imported rhythm section is a more dominating presence than Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Met Orchestra (which was in unusually spirited form). Commissioned and premiered by Opera Theatre of St. Louis in 2013, Champion was written before Fire and expanded for this new production, and though it rambles dramaturgically a bit, the opera has plenty of sharp edges.

Never has the Met gone further into city nitty-gritty with street language and old-school gay-bar talk. “There’s only one pussy in this place. And that’s me!” proclaims Kathy the seedy gay-bar owner, sung with relish by the magisterial Stephanie Blythe. That was gay life in the 1960s—not pretty at all.

Never has the Met gone further into city nitty-gritty with street language and old-school gay-bar talk. “There’s only one pussy in this place. And that’s me!” proclaims Kathy the seedy gay-bar owner, sung with relish by the magisterial Stephanie Blythe. That was gay life in the 1960s—not pretty at all.

Yet the immediacy and realism of Champion doesn’t make its’ story any less operatic. Griffith’s life—growing up in the Caribbean, rising to boxing fame in New York, unintentionally killing a boxing opponent who gay-baited him, and then ending his days on Long Island—has been the subject of books, a documentary film, and a graphic novel, all of which focus on different aspects of his long boxing career and even longer life.

Michael Cristofer has crafted a well-paced narrative for his libretto, with the aging Emile, deep in dementia, having non-chronological flashbacks. We meet the mom who abandoned him (Moore), the opponent he killed (Eric Greene), the quartet of gay bashers who nearly murdered post-retirement Griffith, and, in a brilliant theatrical touch, a boxing match announcer (Lee Wilkof) who goes “meta,” stepping outside the story to tell the audience what he really thinks. Recurring ideas include the need for some sense of home and what constitutes wrong—killing a man while boxing or loving a man in private.

Bringing all of this to life necessitates three different Emiles: Ethan Joseph is the remarkably strong-voiced boy Emile, with Speedo and Owens (whose voices rumble with eerie similarity) as the adult, then aging Emile. Even in his still-young career, bass-baritone Speedo already has here a signature role with his towering stature (onstage, he is only dwarfed by Caribbean stilt-walkers) and commanding voice, heard so memorably weeks back singing Mussorsky’s Songs and Dances of Death with the Met Orchestra at Carnegie Hall. His instrument isn’t as suave and clean as, say, the young James Morris, but it is always infused with a bold sense of meaning.

Bringing all of this to life necessitates three different Emiles: Ethan Joseph is the remarkably strong-voiced boy Emile, with Speedo and Owens (whose voices rumble with eerie similarity) as the adult, then aging Emile. Even in his still-young career, bass-baritone Speedo already has here a signature role with his towering stature (onstage, he is only dwarfed by Caribbean stilt-walkers) and commanding voice, heard so memorably weeks back singing Mussorsky’s Songs and Dances of Death with the Met Orchestra at Carnegie Hall. His instrument isn’t as suave and clean as, say, the young James Morris, but it is always infused with a bold sense of meaning.

Blanchard rightly calls Champion a jazz opera; plot-furthering moments have a jazz riff with declamatory vocal lines on top. Scenes flow in and out of the narrative with a strong emotional contour but little traditional sense of beginning, middle, or end, sometimes with percussion-only accompaniment.

Two standout solo moments are Emile’s Act I “What is a man?” sung with reflective eloquence by Speedo with scoring that has subtle low notes that suggest a pit in the stomach. The even more remarkable “Far Away, Long Ago” sung by Moore (Emile’s mother) has only a lonely bass accompaniment, in pizzicato serpentine counterpoint—deep stuff and portrayed here with great psychological clarity.

The Met’s commitment to Champion is perhaps further suggested by the number of performances—eight—in the run, which ends May 13.

Left: Eric Greene as Benny Paret, Eric Owens as Emile Griffith Sr.

Right: Ethan Joseph as Little Emile

Photos by Ken Howard/Met Opera

Classical music coverage on Musical America is supported in part by a grant from the Rubin Institute for Music Criticism, the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and the Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation. Musical America makes all editorial decisions.

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO