Reviews

Antony and Cleopatra at SFO: John Adams in His Prime

SAN FRANCISCO — John Adams has not tired of defying expectations. Nowhere is this more evident than in his works for the stage, which tend to trigger the most heated, even contradictory, critical reactions.

SAN FRANCISCO — John Adams has not tired of defying expectations. Nowhere is this more evident than in his works for the stage, which tend to trigger the most heated, even contradictory, critical reactions.

Antony and Cleopatra, his latest opera, comes loaded with surprises — and revelations — that show the 75-year-old composer at the top of his game. San Francisco Opera made a bold choice to launch its 100th-anniversary season with the world premiere production of a work whose musical and theatrical challenges alike are considerable. The moving, intricately layered performance I attended (on September 27, a few weeks into the run) justified that choice as singularly foresighted.

Transforming Shakespeare into opera is hardly unexpected per se. The Bard’s intensification of speech through poetry might be seen as analogous to opera’s intensification of emotion through music and the power of the singing voice. But Adams chose one of Shakespeare’s most complex panoramas, a blend of history, epic, and tragedy involving 40 characters in locations on land and sea across multiple continents.

Antony and Cleopatra may be among the world’s most legendary star-crossed couples, yet their motivations remain at best opaque without knowledge of the convoluted historical-political backstory: the misogynist and racist attitudes toward Cleopatra exacerbated by the Romans’ fear of her influence, for example, or the rivalry between military hero Mark Antony and the hyper-ambitious Octavian, Rome’s first emperor-in-the-making (called Caesar throughout the play and opera).

In another unexpected turn, Adams enlisted Elkhanah Pulitzer as director, marking the first time in his operatic career that he has not collaborated with Peter Sellars to create a new work. Likewise unexpected is the fact that Adams himself fashioned the libretto. There are, however, hints of the collage technique of combining unrelated sources, which Sellars developed to generate the librettos for several of his previous stage works. The opera begins with lines from The Taming of the Shrew’s prologue and includes a pivotal scene taken from Virgil’s Aeneid (in John Dryden’s translation) to set Caesar’s hunger for power in relief.

With a few smoothings into more contemporary vernacular, the words are Shakespeare’s (aside from the Virgil scene). Adams’s libretto streamlines the original into two acts totaling nine scenes, winnowing down the characters to a dozen and reassembling some of the lines. Still, it’s a long evening: at some three hours and twenty minutes (including one intermission), the opera well exceeds the typical duration of a staging of the play itself. A couple of scenes could benefit from some pruning.

Adams takes cues for his vocal lines from the rhythms and patterns of Shakespeare’s verse. But within this overall parlando approach, he manages to portray a distinctive personality for each of the principals. Cleopatra’s enormous range communicates her volatility and larger-than-life character. Amina Edris, a newcomer to Adams’s world, celebrates a career-defining triumph as the Egyptian Queen. She effortlessly negotiated the role’s punishing leaps and plunges with lustrous singing and radiated the dramatic presence of a seasoned actor.

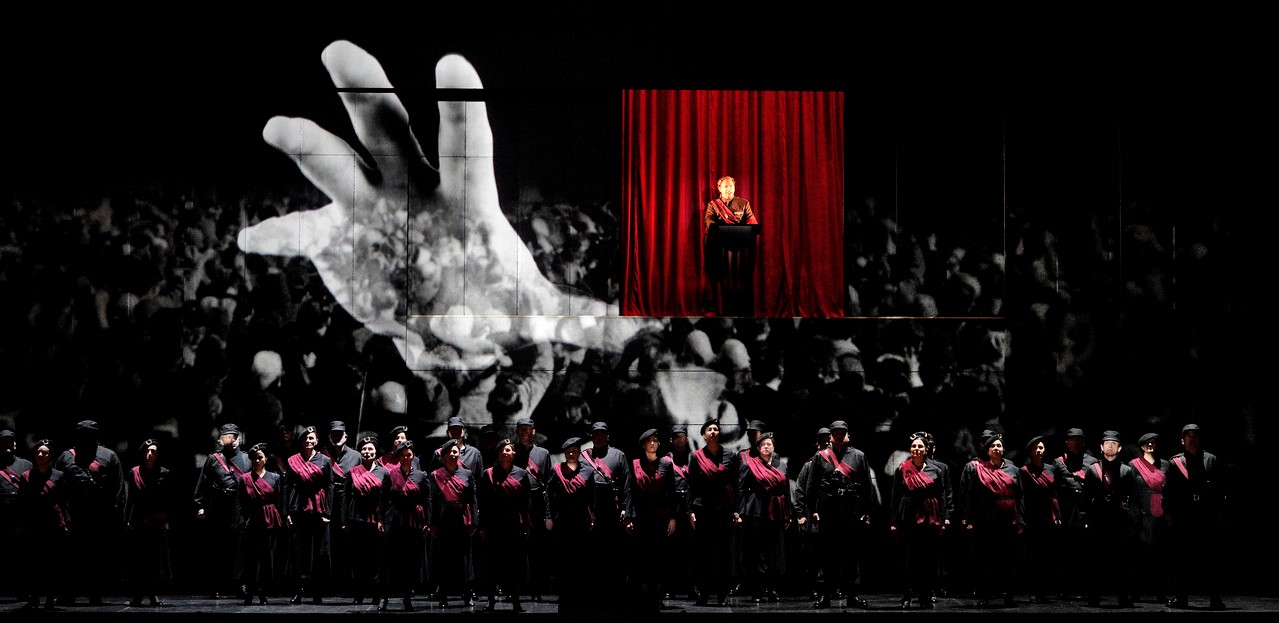

Caesar addresses his troops in San Francisco Opera's Antony and Cleopatra

Gerald Finley also made an unforgettable impression as a multifaceted Antony who experiences a Tristan-like breakdown in the second act. He emphasized Adams’s understanding that this is not just a love story but a hate story, especially in the harrowing scenes with Cleopatra following his defeat by Caesar, which prompt some of the most searingly intense music Adams has ever written. Paul Appleby embodied the icy efficiency coupled with Puritancal contempt written into the role of Caesar — a combination of ruthless tech czar and MAGA demagogue.

There wasn’t a weak link among the rest of the large cast, with particularly affecting contributions from Elizabeth DeShong as an emotionally scarred Octavia (offered in marriage to Antony in a move to cement his bond with Caesar), Alfred Walker as Antony’s perceptive lieutenant Enobarbus, and Taylor Raven in the role of Cleopatra’s loyal attendant Charmian.

Anyone familiar with the dramatic, oracular role played by choruses in Adams’s earlier operas is bound to be disappointed by their limited presence in Antony and Cleopatra. Nor is there much in the way of conventional set pieces, whether arias or ensembles; Adams writes just one duet for the lovers, placed as they each prepare for the Battle of Actium (where the chorus first appears) — the catastrophic naval campaign against Caesar’s forces with which the first act reaches its climax.

What is gained is a newfound urgency, as well as focus, in the pacing of the music drama. Over the large scale of the entire opera, Adams intercuts simultaneous narratives of rise (Caesar’s consolidation of power) and fall (Antony’s disintegration, the cornering of Cleopatra) to powerful effect.

The intimacy of the central love tragedy frames the events but comes increasingly to the fore in the second act, with a corresponding flowering of the despairing lyricism that features prominently in this part of the opera. Another of the score's signatures is the restless energy, alternately nervous and aggressive, that pulsates throughout much of the action. We hear it at the outset, in ostinato rhythmic motifs, violent sforzandos, and sinuously flickering woodwind phrases.

Pulitzer and her design team work wonders translating these impulses into vivid theatricality, facilitating the swift flow of Adams’s dramaturgy. Mimi Lien’s geometrically severe set slides, expands, and shrinks to teleport us at once across the ancient world. There’s time travel as well: the costumes (Constance Hoffman) and projections of old newsreels (Bill Morrison) allude both to Golden Age Hollywood and to Mussolini-style fascism.

Eun Sun Kim navigated Adams’s metrical and timbral subtleties admirably, though I would have preferred a slightly tighter rein for the tremendous build-up of suspense that courses through the first act. She was especially effective in the sorrowfully drifting music of Cleopatra’s extended love-death in the final scene, which leads not to transfiguration but a wistful guttering of the candle.

Top: Amina Edris and Gerald Finley as the star couple

Cory Weaver/SFOpera

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO