Reviews

Dead Man Walking: A Poignant Struggle Toward Grace

Early in the opera Dead Man Walking, based on Sister Helen Prejean’s memoir of counseling death-row inmates, the protagonist’s car gets stopped for speeding. Sister Helen is racing to cover the 150 miles between her New Orleans convent and Louisiana State Penitentiary, where she will meet the convicted killer Joseph De Rocher. The two have been exchanging letters, but this will be their first face-to-face encounter, and her anticipatory anxiety is in large part responsible for her traffic misdemeanor. The motorcycle cop who stops her is fully prepared to give her a ticket, but when he realizes that she is a nun, he lets her go with a warning, and asks her to pray for his ailing mother. We expect this to happen: in the course of the short scene, we can see that the cop has been touched by Sister Helen’s abundant grace.

Ryan McKenny and Joyce DiDonato as De Rocher and Sister Helen, in the moments before his execution

In the two decades since its premiere, Dead Man Walking, with music by Jake Heggie and libretto by the late Terrence McNally, has become the most performed of all contemporary operas. It finally reached the Met on September 26, the opening night of the season, in the new Ivo van Hove staging that had originally been slated for the Covid-cancelled 2020–2021 season. The production demonstrates that the work is unquestionably Met-worthy: a grand opera in a grand space. But its singular accomplishment, achieved through Van Hove’s direction and Joyce DiDonato’s luminous portrayal of its central figure, is to put Sister Helen’s spiritual journey––her seeking of grace––into sharp focus.

The moral question at the work’s center is a complex one. De Rocher is, by any worldly estimation, a monster: a man who has perpetrated a rape and double murder and who now refuses to admit his guilt. Sister Helen, who enlists as his spiritual advisor, is under no illusion about the “terrible thing” he has done, but her faith tells her that he is nonetheless one of God’s children. In its externals, the opera is a chronicle of the events leading up to De Rocher’s execution. But its real action is internal: Sister Helen’s struggle to find forgiveness for “Joe” in her heart, and the moral awakening that leads to De Rocher’s execution-room confession and his plea for forgiveness.

Van Hove’s treatment of the piece is a sober one. Its tone is established by Jan Versweyveld’s unit set: three stark gray walls surrounding a central playing space. Although it accommodates the work’s various settings––the convent school, the prison, an appeals court, the execution room itself––it is at heart a space for inquiry: a forum where Dead Man Walking’s moral issues can be played out. The production directs us toward the spiritual struggle at the work’s core.

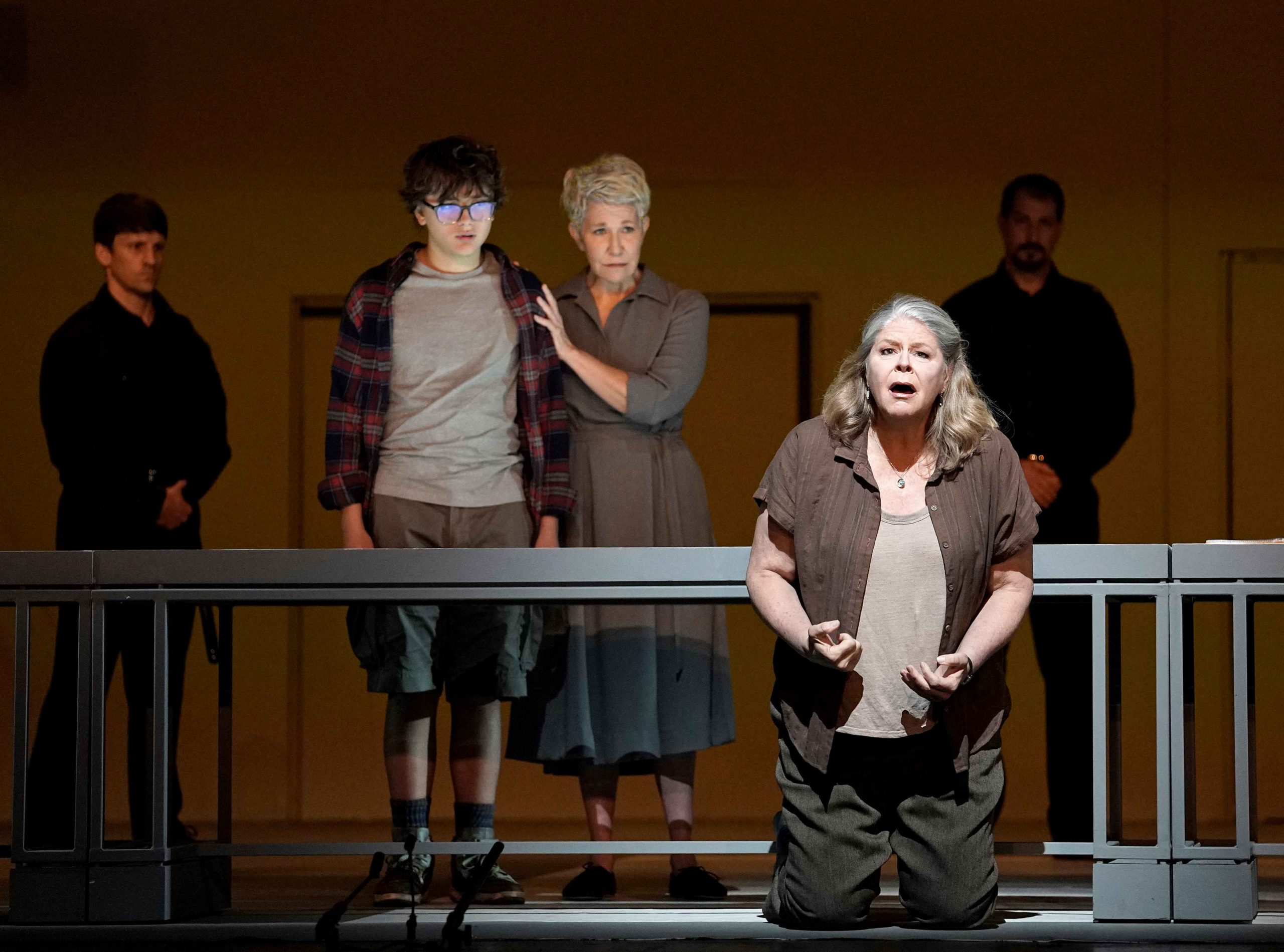

As De Rocher's mother, Susan Graham's expression of despair reads as deep and genuine

DiDonato has played the role of Sister Helen frequently over the years, starting with New York City Opera’s 2002 staging. At the Met’s opening-night performance, her top notes were hollower and less secure than in her 2011 Houston Grand Opera recording of the piece. But her portrayal has only deepened over the years. DiDonato’s immersion in the role––her ability to render its full emotional and moral weight––felt like the result of a commitment to her art akin to Sister Helen’s dedication to her faith.

The Met’s cast was strong all through. Ryan McKinny brought complexity to the role of De Rocher his torso manifestly pumped-up for the assignment. He used rough attacks and the darker colors in his bass-baritone to suggest the character’s barely contained brutality. But for his vulnerable moments he brought out a vein of poignant lyricism, and he delivered De Rocher’s last words––his plea to his victims’ families for forgiveness––with the voice of a child.

Susan Graham, who had played Sister Helen at San Francisco Opera at the work’s 2000 world premiere, here took the role of De Rocher’s mother. She excelled through simplicity of utterance. Her vocal tone was restrained: even in her two big scenes, you were less aware of operatic singing than of human speech. Graham allowed us to experience the character’s sorrow unembellished.

The glowing soprano of Latonia Moore, as Sister Helen’s confrère Sister Rose, immediately conveyed the character’s kindness and capacity for moral support; the one flaw in her singing was her indistinct consonants in her upper register.

The glowing soprano of Latonia Moore, as Sister Helen’s confrère Sister Rose, immediately conveyed the character’s kindness and capacity for moral support; the one flaw in her singing was her indistinct consonants in her upper register.

Rod Gilfry’s portrayal of Owen Hart, the father of the murdered girl, was a portrait of understandable rage and ultimately of vulnerability. Chad Shelton was appropriately smarmy as the prison chaplain; Raymond Aceto, as the prison’s stoic warden, let us glimpse the character’s moral complexity. The motorcycle cop’s scene became a vivid cameo for Justin Austin, successively menacing, comic, and touching. The work’s large ensemble numbers suffered from conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s habitual propensity for letting his orchestra drown out his singers. But elsewhere he brought out Heggie’s gift for creating expressive, emotionally charged vocal lines.

The curtain calls were exhilarating, with huge cheers for the cast and the production team. Heggie received a hero’s welcome, and so, when he led her on for the final bow of the evening, did Sister Helen herself.

Above: Latonia Moore as Sister Rose

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO