Reviews

Hannigan Finesses Multiple Moods with Multiple Skills at the LSO

LONDON—It may be all change at the London Symphony Orchestra, but the programming is as original as ever. Simon Rattle, the outgoing music director, was a sterling champion of new, or modern music, and it appears that in associate artist Barbara Hannigan the LSO has found a worthy successor. This September 14 season opener at the Barbican Centre featured some fascinating and seldom heard late-20th-century curios with the conductor finding a unique way of segueing into a late-Romantic masterpiece, more of which anon.

LONDON—It may be all change at the London Symphony Orchestra, but the programming is as original as ever. Simon Rattle, the outgoing music director, was a sterling champion of new, or modern music, and it appears that in associate artist Barbara Hannigan the LSO has found a worthy successor. This September 14 season opener at the Barbican Centre featured some fascinating and seldom heard late-20th-century curios with the conductor finding a unique way of segueing into a late-Romantic masterpiece, more of which anon.

The program, riffing on the theme of darkness into light, opened with Ligeti’s Ramifications, one of his hazy, proto-minimalist works. Written in 1968, its tiny figurations shift and mingle, creating a sound like the buzz of unearthly and sometimes threatening insects. The composer’s trick of having two dueling string groups tune a quartertone apart shrouds the music in a weird harmonic vapor. Hannigan molded the score with articulate hand gestures—she clearly isn’t one for the baton—blending airiness with musical grit courtesy of a quartet of graunchy double basses.

The short-lived Canadian composer Claude Vivier died 40 years ago, aged just 34, at the hands of a prospective lover in a Parisian apartment. He’s recognized nowadays for his lasting influence on the music of his contemporaries. Born in 1948, his art was fueled by childhood abuse, for example in his use of an invented “nonsense ‘’ language, like a child building a safe place of retreat.

Wo bist du Licht! (Where are you, light?) was written in 1981. It’s a 25-minute monologue, to a text by Vivier himself, for mezzo-soprano and strings, overlayed in places with recordings of Martin Luther King Jr., a pair of French journalists discussing the Vietnam War, and Vivier himself reciting parts of Friedrich Hölderlin’s poem Der blinde Sänger (The Blind Singer). “In a divine sound landscape,” the composer wrote in a note on the score, “there still rings out the voice of the wounded man, who incessantly repeats to God his despair, without which he would not even be sure that God exists.” Bleak, yes, but there’s always some hope that the light might be found, if only the protagonist knew where to look.

A different sound world

Written for a slimmed down line-up of string orchestra and a handful of percussion instruments, it's an extraordinary sound world, although it shares features with middle-period Ligeti and the spectral school of Gérard Grisey. The orchestral prelude bursts on the ear with purring strings whose microtonal harmonics do a decent impression of a vacuum cleaner (in a good way). This is punctuated by terrific wallops on bass drum, gong, and, later, tubular bells, before stalking string chords begin to cut through the texture.

The amplified soloist—a magnetic Fleur Barron complete with glamorous tone and sepulchral lower register—reaches out, pleadingly, her repeated cries of “Where are you, light!” and “Whither? Wither?,” combining harmonically tonal melody and smatterings of sinuous sprechgesang. Later in the piece, Vivier’s invented language calls for extended technique, such as the singer wobbling her lips with her finger. Barron’s focused diction and keen intent made for a moving exploration of absence and loss, and Hannigan invested the whole thing with a powerful sense of ritual.

The intensity of the Vivier was followed by Haydn’s Symphony No. 26, Lamentatione. As one of his Sturm und Drang works, it was not by any means inappropriate, though a bit of an aural jolt into full-scale tonality. Conductor and orchestra had the measure of its mood swings, oscillating between the agitated and the lyrical. The performance might have benefitted from a little more bite in the strings, but there was plenty of drive, and Hannigan certainly knew how to make the melodies sing. The central “Adagio,” was ravishingly played.

The second half of the evening was focused on Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration, one of his more profound tone poems and a perfect exemplar of the evening’s theme of darkness into light. The performance was sumptuous, as one might expect from the LSO. What preceded it though was entirely unexpected.

Italian composer Luigi Nono was driven by socialist ideals and an urge to defend freedom whenever he saw it under threat. In 1962, he was inspired by the plight of an imprisoned Algerian activist to compose a five-minute a cappella work for solo soprano. Returning to the podium, the conductor was herself the soloist in a searching rendition of Djamila Boupacha (Nono gave the work the name of the young woman in question, though the text is a setting of Spanish poet Jesús López Pacheco).

Italian composer Luigi Nono was driven by socialist ideals and an urge to defend freedom whenever he saw it under threat. In 1962, he was inspired by the plight of an imprisoned Algerian activist to compose a five-minute a cappella work for solo soprano. Returning to the podium, the conductor was herself the soloist in a searching rendition of Djamila Boupacha (Nono gave the work the name of the young woman in question, though the text is a setting of Spanish poet Jesús López Pacheco).

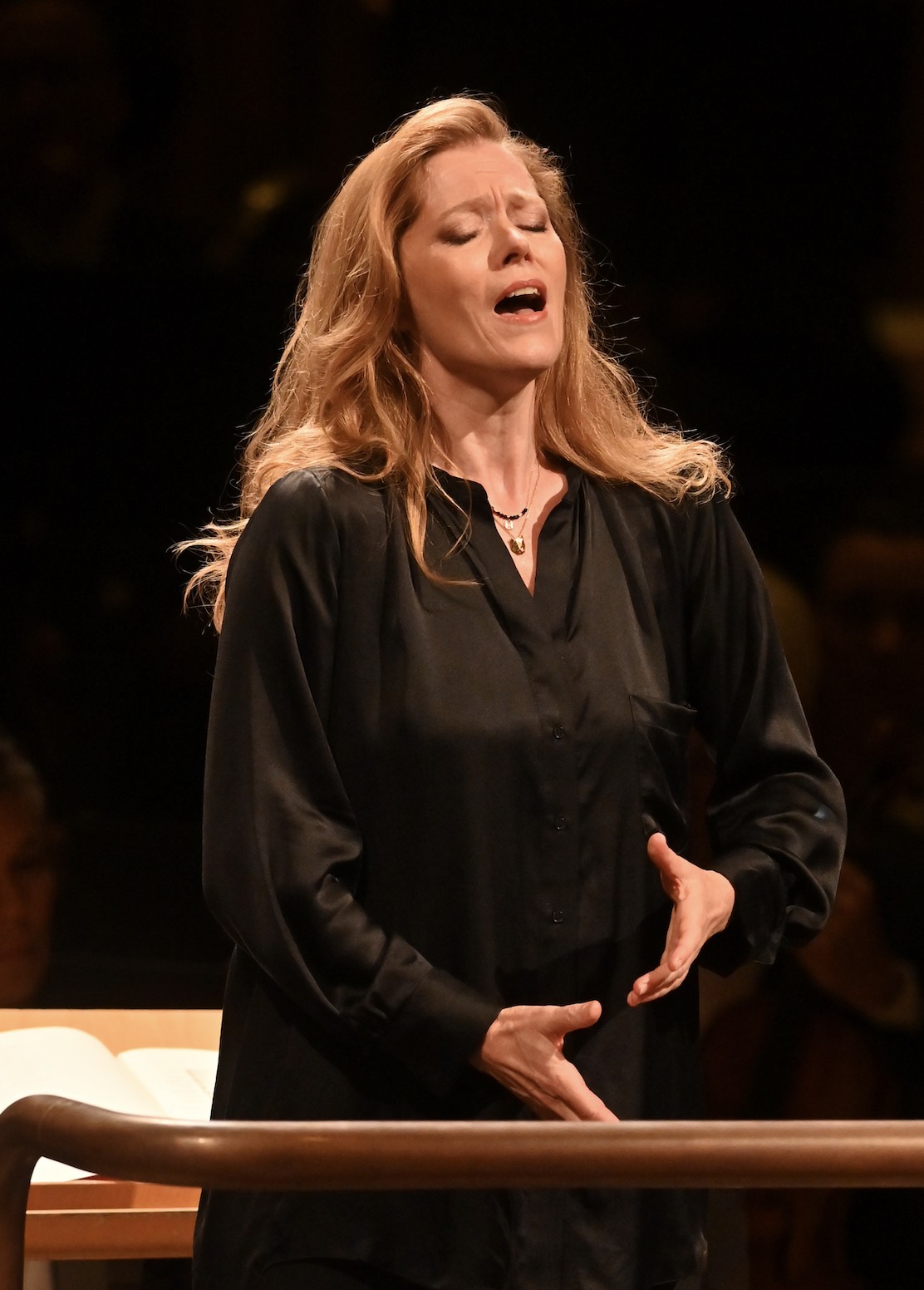

Embraced by a single spotlight, Hannigan held the audience in the palm of her hand as her soprano (full-bodied, with the top pure, ethereal, and frequently thrilling) traversed confusion, despair, and frustration, arriving ultimately at hope. “The light must come,” she concluded, “believe what I tell you.” Then, holding on to the final note, she turned and slipped seamlessly into the opening chords of the Strauss. It was a breathtaking moment, and one that lingered in the mind throughout the concert’s remaining 25 minutes.

Hannigan’s Strauss was notable for its blend of calm and urgency, for distinguished solo performances by flute, oboe, and harp, and for the conductor’s fluent podium manner, her balletic body language adding emotive weight to the achievements of arms and hands.

A fascinating affair, then. Yoking Haydn and Strauss with Ligeti, Vivier, and Nono may not have floated everyone’s boat, but it certainly stimulated the mind, while introducing many, I suspect, to a trio of modernist masterworks. And, let it be noted, the LSO’s brave programming was supported by a pretty decent house.

Photos: Hannigan the conductor, Hannigan the singer

photos by Mark Allan

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO