Reviews

The Met Opens with a New Norma; the Verdict Is (Very) Mixed

NEW YORK—Sondra Radvanovsky expanded her bel canto credentials at the Metropolitan Opera two years ago when she rescued the company following Anna Netrebko’s decision not to appear in Donizetti’s three so-called Tudor Queen operas. A similar situation unfolded as the company prepared a new production of Bellini’s Norma, originally planned for Netrebko, which had its premiere September 25, opening night of the 2017-18 season, with Radvanovsky in the title role. This time Radvanovsky was reprising a role she had sung previously at the Met, to much acclaim.

NEW YORK—Sondra Radvanovsky expanded her bel canto credentials at the Metropolitan Opera two years ago when she rescued the company following Anna Netrebko’s decision not to appear in Donizetti’s three so-called Tudor Queen operas. A similar situation unfolded as the company prepared a new production of Bellini’s Norma, originally planned for Netrebko, which had its premiere September 25, opening night of the 2017-18 season, with Radvanovsky in the title role. This time Radvanovsky was reprising a role she had sung previously at the Met, to much acclaim.

Once again her fervent, grandly scaled portrayal of the Druid princess undone by a sexual relationship with an enemy Roman won her a vociferous ovation. Her big voice surely penetrated every region of the immense house, with delicate pianissimos emerging no less arrestingly than notes sung full voice, a testament to the breadth of her dynamic range. A commanding presence on stage, she acted with thorough involvement in the drama. In the shattering final scene, as Norma prepares to die alongside her repentant lover Pollione while entrusting her children to her father, Oroveso, she laid bare its devastating poignancy.

But, as in the past, the sound of her voice—edgy and sometimes harsh—was often at odds with Bellini’s captivating melodies, whether buoyant or elegiac. Her tone lacks essential resonance and roundedness for this repertoire. There were other problems. What should have been long-spanned legato phrases were sometimes broken by swells of sound. Coloratura too was often smudged, and Radvanovsky showed a degree of self-indulgence by throwing in unwritten high notes, such as a high D at the end of Act 1, at odds with the integrity of the music. In sum, Radvanovsky’s Norma will always inspire a mixed response.

The new production by David McVicar demonstrates why the Scottish director has become such a favorite of Met management. Its approach to the opera is honest and forthright yet allows for novel touches that stimulate one’s thinking. Much of the action takes place at night, which makes sense given the importance of the moon to Druidic rituals. Yet sometimes the stage was so dark it was difficult to see precisely what was going on. In the scene where Norma considers murdering her children, was she sharpening knives? McVicar characterizes the Druids as more belligerent, even barbaric than usual. But surely the violation of societal norms at the heart of the opera presupposes at least some level of social decorum on their part.

McVicar has done some fine work with the principals. We recognize Pollione as a jerk not just from learning in the abstract of his abandonment of Norma, but also from actually seeing him browbeat Adalgisa with abusive behavior into declaring that she loves him.

There is no updating here. Robert Jones’s initial set depicts a forest at night into which the Druids carried wounded or dead warriors on stretchers. Later, the set rises up on the stage elevator, as an enormous thatched hut representing Norma’s quarters emerges from below. This feat of stage wizardly drew a predictable (but unwanted) round of applause.

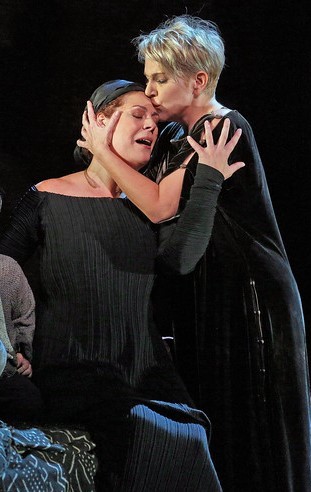

When the Met introduced a new Norma in 1970, Pollione and Oroveso (Norma’s father) were Carlo Bergonzi and Cesare Siepi, but even then it was the women (Joan Sutherland and Marilyn Horne) that counted. So it was here. Joyce DiDonato was a deeply affecting Adalgisa, producing (for the most part) the kind of dulcet tones that eluded Radvanovsky. She also projected a touching vulnerability that seemed to stem both from her contacts with Norma and Pollione as well as the conflicts going on within her. She and Radvanovsky interacted beautifully in their duets.

Joseph Calleja sang Pollione with robust tone and excellent diction. His fast vibrato is not to everyone’s taste (mine included), and it was unfortunate that his vocal color hardly changed from the same bright sound, even after his character’s alleged transformation stimulated by Norma’s self-sacrifice. The able bass Matthew Rose contributed a gruff, surprisingly woolly sounding Oroveso.

Carlo Rizzi was the disappointing conductor, who frequently set tempos that weren’t quite right. The Met’s chorus and orchestra, of course, performed at their usual high level. The program booklet noted that the performance used the recent urtext edition edited by Riccardo Minasi and Maurizio Biondi. Perhaps so, but inflicted on it were the usual cuts, singer drop-outs at cadences, ritardandos, interpolated high notes and other abuses to which Bellini’s score has long been subject. Anyone familiar with Cecilia Bartoli’s recording for Decca, which gives a true representation of the new edition, will recognize the difference between it and what one heard on Monday evening as night and day.

Pictured: Sandra Radvanovsky as Norma, Joyce DiDonato as Adalgisa

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO