Special Reports

BUSTED! The Top Ten Myths of Music Copyright

If you use a copyrighted piece of music and don’t bother to get permission, it’s called stealing.

If you use a copyrighted piece of music and don’t bother to get permission, it’s called stealing.

A copyright is “owned property” just like all types of property—cars, jewelry, boats, houses, coffee makers, etc. Copyrights protect original creative materials such as musical compositions and/or recordings of them. Many people presume that creative property is somehow less valuable or less “property” than other types of property, and so feel free to use it without permission.

Presuming that you are free to use a copyrighted piece of music without permission is like presuming that you are free to take someone’s car without permission—otherwise known as stealing. Permission to use a copyright is granted (or not) by the owner in the form of a license. Licensing the “rights” to use a piece of music means you have the permission of the owner to do so.

Presuming that you are free to use a copyrighted piece of music without permission is like presuming that you are free to take someone’s car without permission—otherwise known as stealing. Permission to use a copyright is granted (or not) by the owner in the form of a license. Licensing the “rights” to use a piece of music means you have the permission of the owner to do so.

Confusion surrounding music copyright is rampant, not only among copyright users but among creators as well. A considerable amount of anecdotal information has been accepted as fact. In no particular order, here’s a list of the most cherished, but incorrect, myths about music copyrights.

MYTH I: No new is good news; besides, it’s easier to get forgiveness than permission.

If you send a licensing request to a publisher or copyright owner and don’t get an objection or any response at all, despite a “good faith” effort, do not assume that you have permission. In addition to being legally wrong, you are assuming that creative property doesn’t have the same value as tangible goods and services. It does.

Similarly, it may be easier, but it’s hardly worth the cost of a lawsuit to assume you can get forgiveness rather than get permission. And that applies to non-commercial and break-even projects as well. If you take a piece of jewelry that you don’t intend to re-sell and later apologize, you still stole it.

Bottom line: If you request a license, and don’t get a response, assume the answer is “no” and select different music. Silence is never golden when it comes to licensing.

MYTH II: My commission, my property.

When a composer is commissioned to create a new work, the mere act of paying for the piece does not automatically convey rights, ownership, or control (unless the composer is also your employee). The right to perform or record the work, even the right to present its premiere, must be negotiated and specified in the commissioning agreement. Otherwise, all rights are exclusively owned and controlled by the composer—including the rights to modify, amend, re-arrange, re-configure, re-orchestrate, and anything else the composer chooses to do. Similarly, paying rental fees for a score and parts does not give the renter the right to perform it.

MYTH III: Mailing my music to myself is the same as copyright registration.

Also known as a “poor man’s copyright,” mailing a score or a recording of your piece to yourself—and then not opening the envelope to prove the date from the postmark—does not give you de facto copyright registration; it just gives you more mail. Copyright registration only occurs through the U.S. Copyright Office. However, more significantly, you do not need to register a work with the U.S. Copyright Office in order to have an enforceable copyright. A creative work is considered “copyrighted” and, thus, protected, the moment it is fixed in any reproducible format. Nor do you need a © symbol to protect a copyright. Conversely, do not assume that material without a © symbol is free to use!

Also known as a “poor man’s copyright,” mailing a score or a recording of your piece to yourself—and then not opening the envelope to prove the date from the postmark—does not give you de facto copyright registration; it just gives you more mail. Copyright registration only occurs through the U.S. Copyright Office. However, more significantly, you do not need to register a work with the U.S. Copyright Office in order to have an enforceable copyright. A creative work is considered “copyrighted” and, thus, protected, the moment it is fixed in any reproducible format. Nor do you need a © symbol to protect a copyright. Conversely, do not assume that material without a © symbol is free to use!

MYTH IV: No money exchanged, no worries.

“Commercial use” of a copyright is not limited to sales or making money, nor does it apply to for-profit organizations only. Any use of copyrighted material that promotes an artist, performance, venue, presenter, product, or service is a “commercial use,” including marketing, promotion, advertising, and even materials used for fund-raising purposes. Truly “non-commercial” use is limited to study, reflection, inspiration, or archival purposes, and does not involve any reproduction in any manner that makes the material accessible to the public. The lack of commercial success or profit is not the touchstone of “non-commercial use.” If it were otherwise, any business venture would be able to use creative material in any manner it wanted so long as they failed miserably.

MYTH V: It’s up to the presenter/venue to collect the proper licenses.

Wrong; it’s up to everyone involved. If an unlicensed song is performed at a venue, the U.S. Copyright Act allows all the parties involved in the performance—the venue/presenter, the artist, the artist’s agent or manager, the producer, the promoter, and anyone else—to be sued by the publisher or copyright owner. Stealing a song is like robbing a bank—the entire gang is arrested regardless of who broke open the safe, who drove the get-away car, or who simply served as look out; they all participated in the robbery. All parties are responsible for the proper licensing. Who obtains which license and bears the cost is all a matter of negotiation. There is no industry standard!

MYTH VI: An ASCAP license gives me permission to perform, reproduce, record, and/or broadcast a work.

In order for music to be “performed” (either live or via a recording) in a public place, there needs to be a “performance license.” Most often, these are obtained from one of the Performance Rights Organizations: (ASCAP, BMI, or SESAC). But an ASCAP license only covers ASCAP composers, and BMI and licenses only cover BMI or SESAC composers. So, depending upon how many works you want to perform, you may need licenses from all three. However, a performance license only gives you the right to perform the composition. A composition being used as an integral part of a story or plot, or interpreted with movement, costumes, or props—also requires a “dramatic license,” usually granted from the composer or publisher to the producer of the dramatic work.

In sum, you always need a performance license to “perform” a composition. Whether or not you also need a dramatic license depends on the context in which you use the composition. Put another way, if you stand still and perform you only need a performance license. If your performance involves sets and costumes, tells a story, develops a character, or interprets the composition, you will need both dramatic and performance licenses. [Information on grand rights]

There are other licenses you may need as well: if you plan to make an audio recording of your performance, you will need a “mechanical license.” If you plan on making an audio-visual recording of your performance, you will need a “synchronization license.” If you plan to permit a broadcast of your performance, you will need a “broadcast license.”

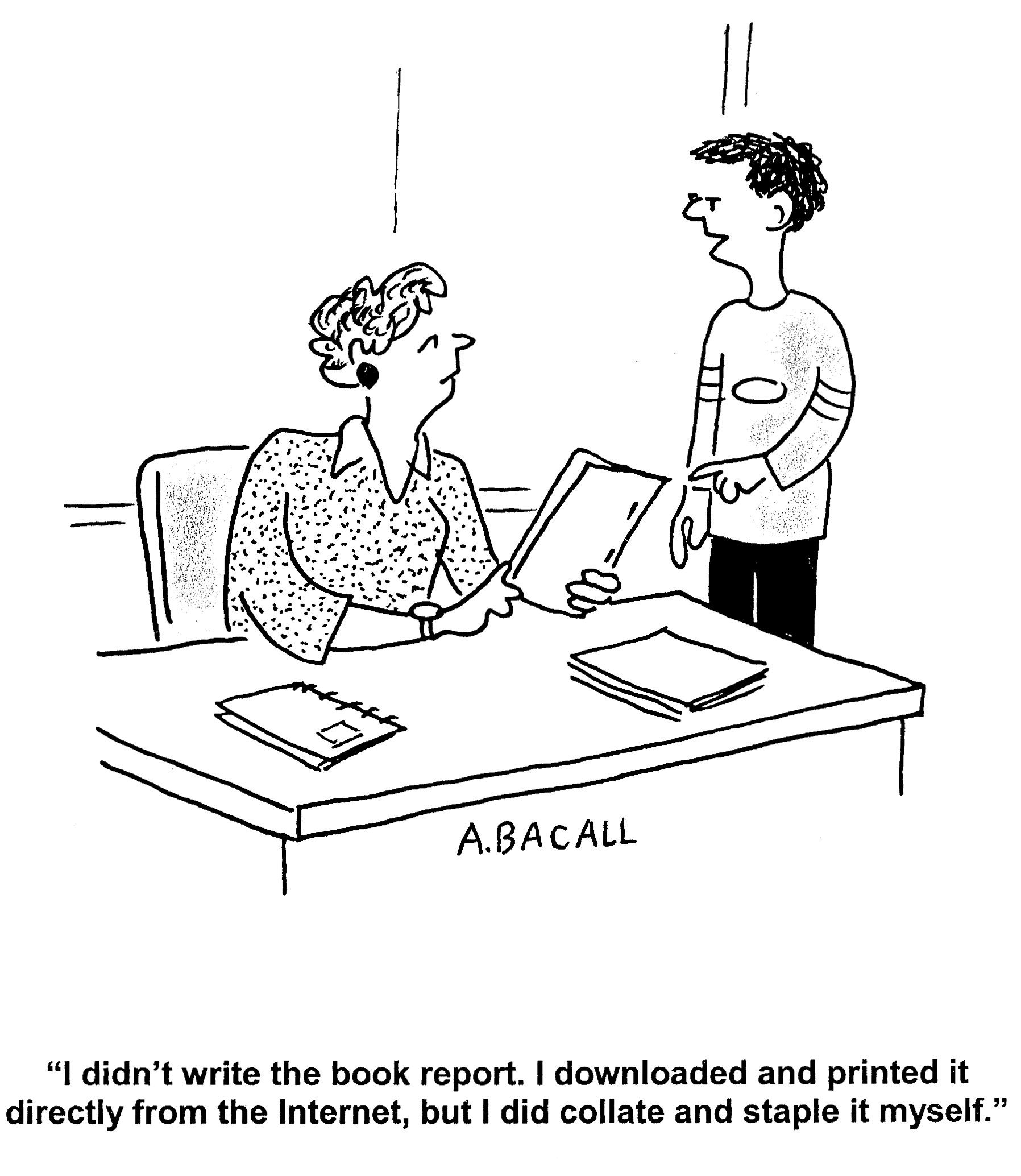

MYTH VII: If it’s on the Internet, it’s free.

Just because someone uploaded a video or audio clip (or any other creative material), does not mean they had the right to do or so. And even if they did, that doesn’t give you the right to copy and use it as you wish. Digital materials carry all of the same copyright laws and protections as their traditional, hard-copy counterparts. The Internet is publically accessible, but that doesn’t mean everything on it is free or in the public domain.

MYTH VIII: If I have permission to use a piece, I can re-arrange or creatively reinterpret it too.

Regardless of whether you have a performance license, a dramatic license, a mechanical license, or a synchronization license, you only can use creative property as written. While you can perform the work in your own style, artistry, expression, etc., you may not re-orchestrate or re-arrange it in a way that changes its fundamental nature. A license granted by ASCAP, BMI, or SESAC to perform a string quartet does not give you the right to rearrange it for banjo, bagpipe, saxophone, and zither (tempting as that may be), nor does a mechanical or synchronization license give you the right to write new lyrics to a song licensed by ASCAP. If you want to make changes, you need, as always, permission and you need to specify your plans.

Regardless of whether you have a performance license, a dramatic license, a mechanical license, or a synchronization license, you only can use creative property as written. While you can perform the work in your own style, artistry, expression, etc., you may not re-orchestrate or re-arrange it in a way that changes its fundamental nature. A license granted by ASCAP, BMI, or SESAC to perform a string quartet does not give you the right to rearrange it for banjo, bagpipe, saxophone, and zither (tempting as that may be), nor does a mechanical or synchronization license give you the right to write new lyrics to a song licensed by ASCAP. If you want to make changes, you need, as always, permission and you need to specify your plans.

MYTH IX: “Fair Use” means making any use which is fair.

Wrong. “Fair Use” is a legal doctrine that allows you to use a small amount of a copyrighted material only for specific, limited purposes. It is a defense to a claim of copyright infringement and is determined on a case-by-case basis. There is no “minimum” amount of music, words, recordings, footage, or anything else that automatically constitutes fair use. If there is ever a dispute, it is a judge who gets to decide what is fair, not you. Just because you will not be making any money, really-really-really need it for a really-really-really great artistic concept, can’t afford to pay for it, are a nonprofit organization that needs it for a children’s education project, does not make your use of copyrighted material “fair” or even permissible.

MYTH X: If a composer gives me a recording of the work, that implies permission to use it.

Any time you want to use an existing recording of a work, whether on your web site or as a soundtrack, you will need a license from the composer/publisher as well as a license from the owner of the recording (which is often a record label). That’s right—two separate licenses. The copyright law creates a copyright in compositions and a separate copyright for the recording of it. If the composer owns both the composition and the recording, then you’re in luck. Otherwise, if you plan to do anything other than listen to it, there are many hoops through which to jump. When it comes to music licensing there are really only three basic rules:

- Always ask permission

- Know whom to ask and for what

- Never assume

It may seem like a lot of legwork, but keep in mind that, more often than not, you will be able to get the licenses you need, provided you request them properly and far enough in advance. Never leave licensing requests to the last minute and do not assign such an important task to a volunteer or an intern helping out at your office. Also, bear in mind that the same rules that may seem to thwart your ability to use the music you want also protect your creative endeavors.

Brian Taylor Goldstein is a partner in the law firm of GG Arts Law and a Managing Director of Goldstein Guilliams International artist management. He writes the weekly blog Law and Disorder: Performing Arts Division for Musical America.

FEATURED JOBS

FEATURED JOBS

RENT A PHOTO

RENT A PHOTO